On 30 November, Russia’s Supreme Court declared the “international LGBT public movement” an “extremist organisation”, effectively outlawing it. Now, the exhibition of any symbol deemed to contain “LGBT elements” (for example, the rainbow flag) may lead to fines or even arrests.

Novaya Europe looks at the history of the LGBT movement in Russia from the fall of the USSR to the present day.

LGBT in the late Soviet Union

The first wave of LGBT activism in the USSR began in the late 1980s, during the period of glasnost (openness) under Mikhail Gorbachev. Members of the LGBT community — along with some activist allies — started to gather in small groups.

It was finally possible to talk openly about sex and relationships. 1989 saw the publication of the first issue of Tema — the first newspaper in the USSR dedicated to the lives of “sexual minorities”, as they were called at the time.

“We needed to break through the information blockade, to explain that we exist and that gays are ordinary, perfectly normal people,” Roman Kalinin, the newspaper’s publisher, recalled.

The newspaper was just one of many projects initiated by the newly-formed Association of Sexual Minorities (Union of Lesbians and Homosexuals). This pioneering LGBT non-profit fought to lift a ban on “sodomy” dating back to Stalin’s time, helped HIV/AIDS-positive individuals, and worked to reform public opinion about the LGBT community.

Demonstration in support of gay rights in Moscow in 1991. Photo: Robert Wallis / Corbis / Getty Images

Freedom at the turn of the century

These movements of the late ‘80s continued to grow after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. The first significant event for the post-Soviet LGBT movement was the repeal of the law on “sodomy” in 1993.

By the mid-1990s, many LGBT people in Russia had started to feel that “things were okay”, the sociologist Alexander Kondakov said. Throughout the country, film festivals, conferences, and cultural events dedicated to issues of LGBT life were held freely and without repression. In 1999, Russia adopted a version of the International Classification of Diseases in which homosexuality was no longer considered a mental disorder.

In 1996, the Russian-language internet portal Gay.ru was launched by LGBT activists Ed Mishin and Dmitry Sannikov. Over the next few years, Gay.ru would team up with similar projects to host parties and events in Moscow, conduct HIV prevention activities, and provide psychological support to members of the LGBT community.

The Russian entertainment world also seemed to embrace the change, with artists like Boris Moiseev, Shura, and Eva Polna incorporating LGBT themes into their public images and performances. In 2003, Russia was represented at Eurovision by t.A.T.u., a female duo who performed songs with homoerotic themes and kissed on stage. Before the final, there were even rumours in the press that the show’s organisers were concerned about the “level of provocation” in t.A.T.u.'s performance.

Russia’s state-controlled Channel One not only supported the group, whose image was built around themes of same-sex love, but even appealed the results of the competition in the hope that the duo would be awarded first place.

However, this increased media representation did not satisfy all the needs of LGBT Russians at the turn of the century. Beyond the websites and magazines of the late 1990s and 2000s, queer people in Russia felt an increasing need to create a more structured community that they could turn to for help.

In 2005, the GayRussia LGBT rights project was formed, aiming to combat all forms of discrimination. Despite police resistance and the objections of Moscow officials, activists from the organisation held four pride parades in Moscow between 2006 and 2009.

Participants of an unauthorised pride parade are arrested in Moscow, 2006. Photo: Nikolay Alexeyev / Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED)

The number of human rights organisations striving to support queer people continued to grow. In 2006, the Russian LGBT Network was launched with a goal of uniting regional initiatives and projects to combat discrimination. The Network held a number of educational events throughout the 2000s, such as the Week Against Homophobia. In 2009, the first report on the legal status of LGBT individuals in Russia was released, thanks to the efforts of activists from the network and the Moscow Helsinki Group.

Russia’s identity crisis and traditional values

Alongside increasing tolerance towards LGBT people in some areas of Russian society, however, other societal transformations were also underway. Many academics have described a significant change in gender roles following the collapse of the Soviet Union. With the dissolution of the USSR and its “traditional” model for heterosexual relationships, many new Russians, especially men, found themselves in an identity crisis.

Tatyana Ryabova, a professor at Herzen State Pedagogical University, calls the late 1990s a period of “demasculinisation”. For many Russian men, defeat in the Cold War symbolised their inability to support and defend their country, she said. Homosexuality and the LGBT community as a whole became symbols of the “free West”, which these bruised and emasculated segments of Russian society viewed with increasing scepticism.

Some regional laws began to give voice to this attitude. In 2006, a ban on “LGBT propaganda among minors” was introduced in the Ryazan region — the first modern Russian law to openly discriminate against LGBT people.

Lena Katina and Yulia Volkova from the group t.A.T.u. kiss during a concert on 3 October, 2002. Photo: Wojtek Laski / Getty Images

The same year, Putin gave his annual address to the Federal Assembly, defining the course of Russian politics for years to come. In his speech, he acknowledged Russia’s demographic crisis for the first time and emphasised the importance of preserving “traditional values”. Many scholars view this as the moment when the Russian government took a "conservative turn”.

Shortly after the appearance of the “conservative turn” at home, Russian leadership began to broadcast similar values to its international partners. In his famous speech at the 2007 Munich Security Conference, Putin made several statements about the “unacceptability” of a “unipolar world”.

According to political scientist Nikita Sleptsov, it was in this context that the Kremlin increasingly needed to find a “common enemy” around which it could unite the population. The strategy it chose was what Sleptsov terms “conservative heteronationalism” — in other words, the demonisation of the LGBT community.

In subsequent years, tensions in society continued to escalate, culminating in the 2011 Bolotnaya Square protests against the results of the parliamentary elections. In 2012, a new wave of protests swept the country, this time against the presidential elections in which Putin had secured another term. The protest movement included many supporters of the LGBT community, which gave the government yet another reason to demonise them.

Participants of a rally “For Fair Elections” on Bolotnaya Square protesting against violations in the parliamentary elections on December 10, 2011, in Moscow. Photo: Alexander Aleshkin / Epsilon / Getty Images

State-sponsored homophobia continued to grow and, in 2012, a law banning “gay propaganda” was adopted in one of Russia’s “freest cities” — Saint Petersburg.

Official homophobia

In the early 2010s, the state began to actively confront the LGBT community, which it had largely ignored until that point. State television increasingly featured segments that criticised or vilified members of the LGBT community. Between 2006 and 2013, over ten Russian regions adopted regional laws banning “LGBT propaganda” among minors.

Soon, a version of this law at the federal level was introduced in the State Duma. Not all deputies supported the bill — surprisingly, its critics included the far-right populist Liberal Democratic Party, whose leader, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, suggested that a ban on LGBT “propaganda” would only direct more public attention to same-sex relationships.

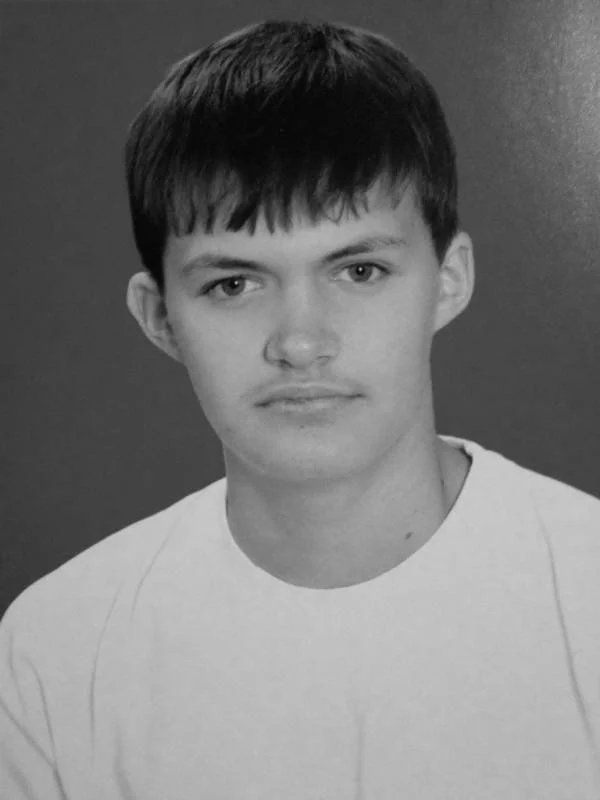

In a way, Zhirinovsky was correct: increasingly negative coverage of LGBT issues led to a rise in high-profile hate crimes against LGBT people. In May 2013, when the federal ban was still under discussion, three former school friends in Volgograd tortured 22-year-old Vladislav Tornovoy to death because of his sexuality. They broke his ribs, inserted two glass beer bottles into his rectum, then hit his head with a 20-kilogramme stone.

Vladislav Tornovoy. Photo: VK

Tornovoy’s death provoked outrage and shock in Russia’s LGBT community. Yelena Mizulina, a deputy who was one of the main supporters of the propaganda bill, received the brunt of the criticism. Despite the public outcry, however, Putin signed the federal law banning “LGBT propaganda” a month after Tornovoy’s murder.

The anti-LGBT campaign continued to gain momentum: half a year later, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev signed amendments to the adoption law prohibiting foreign citizens in same-sex marriages — and those living in countries where same-sex marriage was legal — from adopting Russian children. With each passing year, the number of countries on the list increased.

The social impact of these laws appears significant. According to research by Alexander Kondakov, the percentage of homophobic hate crimes doubled between 2011 and 2017. Kondakov said his methodology was very conservative, so there were likely even more cases.

If the situation was worsening nationwide, LGBT people faced even harsher discrimination in Russia’s most conservative regions. In Chechnya, at least a hundred men were arrested — and three killed — because they were “suspected of being gay”, as Novaya Gazeta reporters exposed in 2017.

When an American journalist questioned Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov about the report, he claimed that there were “no gays” in Chechnya: “We don’t have any gay people. And if we do, take them away from us.”

Total ban

Russia’s war against Ukraine has also affected the LGBT community. In December 2022, Putin signed a law imposing a complete ban on the “propaganda of non-traditional relationships” and the “propaganda of gender change and paedophilia”. The new law dramatically expanded the scope of the previous ban, which had only outlawed “propaganda” targeted at minors.

In response to the law, bookshops began removing queer literature from their shelves, and streaming platforms independently began to take down and block films and podcasts that mentioned “non-traditional relationships”.

In July 2023, the State Duma implemented a total ban on “gender change” in an attempt to "protect Russians from degeneration”. The law prohibits hormone therapy and gender-reassignment surgery and prevents transgender people from changing their gender in official documents.

Finally, on November 30, 2023, the Russian Supreme Court declared the “international public LGBT movement” an extremist organisation. The hearing, which lasted just four hours, was held behind closed doors, with no defendant in the courtroom.

It is not yet clear how the law will be enforced. According to the Russian Criminal Code, participating in an extremist organisation is punishable by up to six years in jail, while founders of extremist communities can get up to 10 years behind bars. “Public calls for extremist activities” can lead to a fine of 100,000 to 300,000 rubles (€1,000 to €3,000) or up to four years in prison.

In the days since the Supreme Court ruling, a number of Russian LGBT rights groups have already dissolved, explaining that the new legislation puts their Russia-based employees at risk of imprisonment. In early December, police conducted raids on four LGBT-friendly venues in Moscow, claiming they were looking for drugs. Central Station, a longstanding Saint Petersburg gay club, announced its permanent closure last Friday.

Not all organisations have folded entirely, however: the Samara-based LGBT rights group Irida signalled its intention to fight the new law, submitting an appeal against the ruling. Other organisations have begun fundraising campaigns to evacuate LGBT activists from Russia and written petitions calling on Western countries to simplify visa procedures for Russian LGBT individuals.

This latest legislation represents the culmination of years of state-sponsored homophobia in Russia, leaving the country’s already-isolated LGBT community more vulnerable than ever.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]