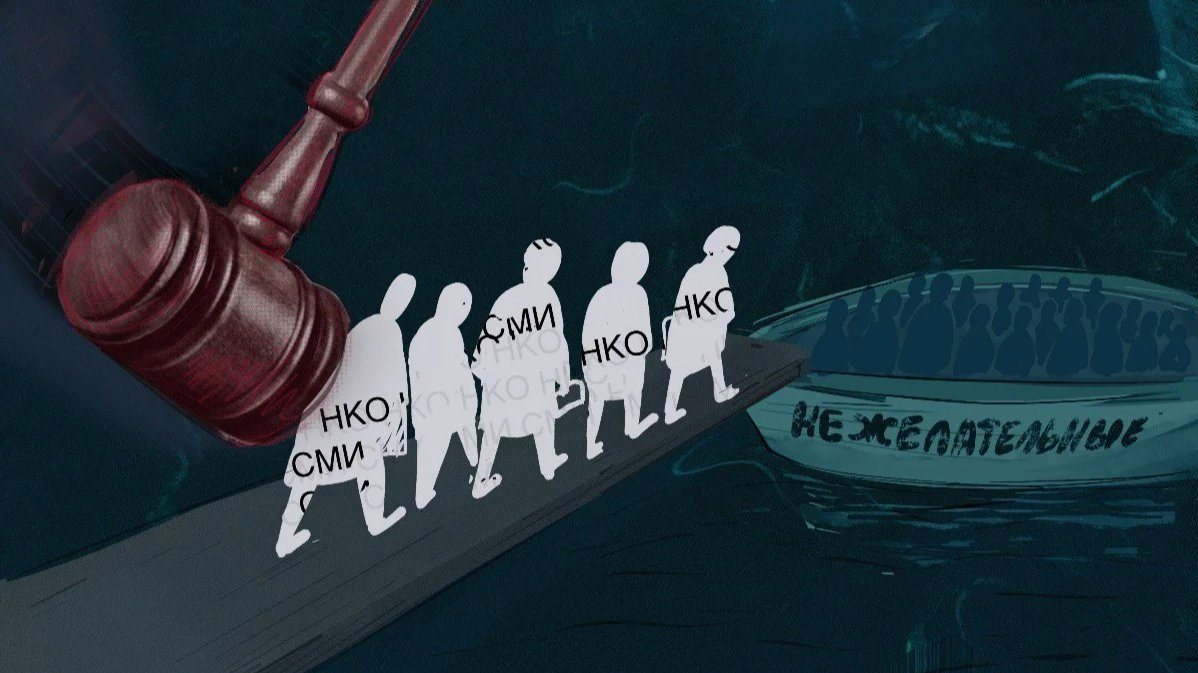

Under a decade-old law, any organisation that displeases the Kremlin can simply be classed an “undesirable” organisation, immediately compelling it to dissolve itself as a legal entity in Russia.

Co-operation with or working for an organisation deemed undesirable can lead to prison sentences of up to six years. While the list of undesirables began slowly, it is now growing exponentially, and in the first three months of 2024 alone, the Russian authorities designated more organisations “undesirable” than they did in the whole of 2022.

More than two-thirds of the organisations deemed undesirable have been given the designation since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. For the Kremlin, though, this is more than just a weapon to persecute independent nonprofits and the independent media — it is the embodiment of a policy of isolation from the rest of the world.

Mission creep

The law on undesirable organisations came before the State Duma, Russia’s lower house of parliament, in November 2014. Its stated aim was to combat the emergence of foreign-financed “extremist organisations” in Russia, and as a device for the redress of sanctions imposed by the US and others on Russian companies following the illegal annexation of Crimea earlier that year.

The bill was signed into law by Russian President Vladimir Putin in May 2015, and came into force the following month. At the time, one of the State Duma deputies who tabled the bill, the Liberal Democratic Party’s Anton Ishchenko, told Russian business daily Vedomosti that it had been designed to eliminate potential external threats. “It is unacceptable that any foreign organisation should have been able to distribute weapons to people, as happened in Ukraine,” he said.

“Anyone, including overseas commercial organisations, can end up on the list, and the worst thing about the law is how vaguely worded it is,” lawyer Yelena Lukyanova said at the time.

View of Moscow City Court, 29 November 2021. Photo: Yuri Kochetkov / EPA-EFE

The first organisations were deemed undesirable in 2015, back when the term referred to an overseas or international nonprofit whose activities were deemed to “pose a threat to the foundations of the constitutional system, the country’s defence capabilities or state security”.

In 2021, the law was broadened to cover legal entities which may not threaten the constitutional order themselves, but that act as an intermediary for other undesirable organisations, for example by conducting financial transactions.

The authorities argued the law was needed to fight international terrorism, but it was almost immediately clear that its real purpose was very different.

Further amendments to the law that introduced prison sentences for those convicted of involvement with an undesirable organisation beyond Russia’s borders came into force in July 2022, amid a mass exodus of Russians following the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In Russia, any undesirable organisation is legally obliged to dissolve itself. Banks are banned from financing undesirable organisations and private citizens cannot have any involvement in their activities.

Employees at such organisations are liable to both administrative and criminal charges. Staff members and individuals cooperating with undesirable organisations can be fined up to 15,000 (€150), public officials up to 50,000 (€500) and other organisations cooperating with them up to 100,000 rubles (€1,000) for a first offence. Receiving two such fines within a year may lead to criminal charges. The law stipulates a fine of up to 500,000 rubles (€5,000), community service for up to five years, and prison terms of two to six years. Directors of undesirable organisations face immediate criminal liability.

Lawyer Alexey Pryanishnikov says organisations are now being declared undesirable at a similar pace to people being registered as foreign agents. He told Novaya Europe — which itself was deemed an undesirable organisation in 2023 — that there were now 155 undesirable organisations in total. While between 2015 and the end of 2021, 49 organisations were designated undesirable, a further 106 have been added to the list in the past two years alone.

Pryanishnikov said that the start of the war against Ukraine had led to an increase in the number of nonprofits declared undesirable, while many media outlets had also been put on the list in order to tighten military censorship.

Expedited undesirability

There are currently 155 undesirable organisations. Novaya Europe calculated that two to three organisations went on the list each year from 2015 to 2019, but the rate at which groups were deemed undesirable began to pick up pace in 2020. It hit its peak in 2023, with 56 new designations, but 2024 may even exceed that number: in the first three months of the year alone, there have been more undesirable designations than in the whole of 2022.

Not a month has gone by since the beginning of 2023 without someone being declared undesirable. Lawyer Maxim Olenichev told Novaya Europe that over two thirds of the organisations had been placed on the list since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, an accurate reflection of Kremlin rhetoric on limiting Russia’s ties to the Western world.

Organisations working to promote democracy, civil society, education and human rights are most commonly named undesirable, our research showed. But the list also includes media outlets, religious and even environmental organisations. Of the latter, both the World Wildlife Fund and Greenpeace International have been deemed undesirable and banned.

Greenpeace activists at a protest in front of the Russian government building in Moscow. Photo: Sergey Ilnitsky / EPA-EFE

Religious organisations were targeted most often under this law in 2021, six in all from Ukraine, Latvia and the US. By 2022, the media became the most frequently targeted sector, again with six cases. In 2023, eight media organisations were declared undesirable, but due to the growing pace of designations, that was only enough to place fourth.

Most undesirable organisations come from the US and Germany, followed by Ukraine. The graph only features countries with two or more undesirable organisations.

The first to suffer

The first organisations to go on the list in 2015 were the National Endowment for Democracy, Open Society Foundations, and the US-Russia Foundation for Economic and Legal Development, all of which are based in the US.

Olenichev told Novaya Europe that organisations have been placed on the list both steadily and in waves.

“The undesirable list is a political tool to respond to changes in Russian government policy. First, they decided to get rid of the philanthropic activities of the Soros Foundation. By 2015, the foundation had helped publish hundreds of books on the humanities for Russian libraries, provided internet access at universities and promoted science and education. The authorities saw this as a threat. The foundation stopped all its activities in Russia,” he says.

The Russian authorities designated the UK-registered Open Russia and its sister organisation Open Russia Civic Movement, both linked to former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky, undesirable in 2017. Open Russia activists were among the first to be prosecuted under the undesirable law. The Mass Media Defence Centre calculated that almost 45% of prosecutions were administrative cases for association with the organisation.

Pryanishnikov confirmed to Novaya Europe that Open Russia is the record-holder in terms of persecution, with over 350 cases.

BBC News Russian reported in 2020 that in the three years since Khodorkovsky’s UK-based organisations were designated undesirable, investigators had initiated about 300 cases against Russians who had supported Open Russia in some way. Almost all charges were based on social media reposts.

The repressive tool soon spread to other areas of civil society, and a big new wave of repression was unleashed in 2021 when various human rights groups, European election monitors and independent media organisations were designated undesirable.

The first Russian media organisation, Project Media, Inc., associated with independent investigative journalism outlet Proekt, was designated undesirable in 2021, followed by three other independent outlets, IStories, The Insider and Meduza the following year.

The number of undesirable organisations increased many times over once Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and that number included many more independent media outlets, most notably TV channel Dozhd and Novaya Gazeta Europe.

Last year, exiled journalist and writer Dmitry Bykov was fined for his involvement with an undesirable organisation over a video he recorded for Novaya Gazeta Europe’s YouTube channel with veteran Russian rock star Boris Grebenshchikov.

Prosecuting the opposition

One high-profile undesirable case concerned the former director of Open Russia, Andrey Pivovarov, who was removed from a flight to Warsaw from St. Petersburg’s Pulkovo Airport on 31 May 2021 and arrested.

A court in Krasnodar delivers its verdict in Andrey Pivovarov’s trial for running an undesirable organisation, 15 July 2022. Photo: Anatoly Rodnikov / Kommersant / Sipa USA / Vida Press

Shortly beforehand, Open Russia had announced that in view of the tightening of the law on undesirable organisations, it would be forced to cease its activities and shut down its offices in Russia.

A court in the southern city of Krasnodar ultimately sentenced Pivovarov to four years in prison for leading an undesirable organisation.

Lawyer Anastasia Burakova calls this rubber-stamp law enforcement. “Persecuting people not even involved in undesirable organisation activities is a repressive tool used against civil society and undesirable people engaged in activities that irritate the Kremlin.”

While in the past the authorities mainly prosecuted activists and nonprofits for online statements or for involvement in the activities of an undesirable organisation, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, there has been an increase in cases against people who had never had any kind of public profile before, Olenichev told Novaya Europe.

Olenichev added that the authorities didn’t now use the law to prosecute the undesirable organisations themselves — they have all discontinued their work in Russia. Instead, the law is applied to Russian citizens and organisations which, as a rule, have remained in Russia and shared material produced by an undesirable organisation online.

“The Russian authorities have organised repression in such a way as to sow fear in Russian society for any co-operation or involvement with an undesirable organisation,” he said.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]