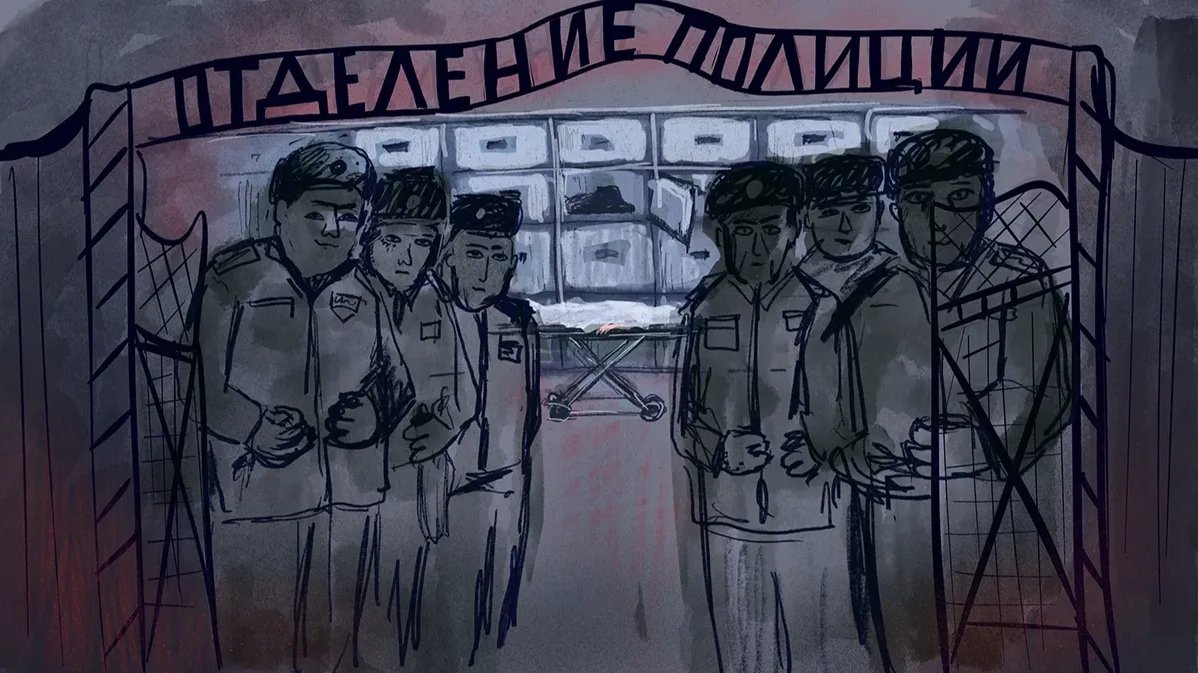

In 2023, the number of sudden deaths in police custody — at precincts, in police cars and detention centres — more than doubled across Russia, bringing the number of people known to have died as a result of police brutality in the past 15 years to at least 1,330.

Novaya Europe analysed over 120,000 reports from Russia’s Investigative Committee as well as 5,000 media stories to understand who exactly is dying in police custody and how the war in Ukraine has served to amplify state violence.

After recent protests in support of jailed political activist Fail Alsynov in the central Russian republic of Bashkortostan, one of the protesters, Rifat Dautov, died in a police van on 26 January. State-controlled media claimed the cause of death was surrogate alcohol poisoning.

Torture and police violence have long been well-known issues in Russia, and as there is no requirement for the police to disclose deaths that occurred in custody, it is only thanks to the efforts of the media or third party initiatives that such incidents become public knowledge at all.

Though the authorities attempt to minimise public discussion of such incidents, last year was the worst in terms of deadly police violence in seven years, according to Novaya Europe’s calculations, with at least 70 people dying in detention centres or immediately after visiting a police station — double the figure from the previous year.

Nikita Zhuravel, a 19-year-old who was arrested for burning a copy of the Quran, was beaten up by Adam Kadyrov, son of the Chechen head Ramzan Kadyrov, while in custody in September. Artyom Kamardin, imprisoned for reciting anti-war poetry, was reportedly raped with a dumbbell during a police raid. These are just two better known cases of police brutality in recent years amid many others.

“Ten years ago, you would most likely already have a criminal investigation into such conduct,” says Sergey Babinets, lawyer and head of the human rights organisation Crew Against Torture, but officers who use violence against detainees have increasingly enjoyed impunity.

Gone to war

Police major Mikhail Balashov was told that there were no available officers as he repeatedly called dispatchers and colleagues on the night of 14 January 2020 in an attempt to find responders for an emergency call in the western Siberian city of Kemerovo.

That night, Kemerovo resident Vladislav Kanyus spent several hours torturing his ex-girlfriend, the 23-year-old Vera Pekhteleva. Neighbours heard her screams and called the police at least seven times, but no one ever arrived. The police only attended the scene after being told that a corpse had been found once the neighbours broke down the door to Pekhteleva’s apartment, only to find that they were too late.

Kanyus was sentenced to 17 years in prison, but was later pardoned and sent to fight in Ukraine. Alongside him went 15,000 Russian police officers.

Russian Interior Minister Vladimir Kolokoltsev has claimed that a further 42,000 officers are needed to operate in the “new territories” — the occupied areas of Ukraine.

The Interior Ministry has been suffering a staffing shortage since before the war — as evidenced by the 2020 murder of Vera Pekhteleva — but things deteriorated quite sharply after Russia invaded Ukraine. Now, in addition to its old issues, the ministry needs to deal with new problems: it is losing its officers to conscription and combat, while other employees have left their jobs for fear of being sent to war.

Experts interviewed by Novaya Europe say that the increase in violence against detainees and suspects is a predictable consequence of staffing shortages. “The system continues to operate with set quotas for the number of crimes that must be solved, but there aren’t enough people to do the solving,” a Russian human rights activist who wished to remain anonymous told Novaya Europe.

Non-existent stats

As there are no publicly available statistics on deaths in police custody in Russia, we can only extrapolate a lower estimate based on cases in which law enforcement agencies chose to disclose a death in custody for whatever reason. The actual number of deaths may be far higher.

Our research found reports of 1,330 deaths since 2010 in police stations, pre-trial detention centres, and other facilities in which a detainee can be placed. Of these, 1,257 were men and 73 were women.

The youngest victim we found was 13 years old. In July 2023, a teenager from Yakutia was taken home in the boot of a police car and subsequently pronounced dead by medics. The police said the boy had been drunk, though his family insisted that there had been no smell of alcohol on his body. An internal investigation resulted in the police officers and their superiors being merely reprimanded.

Most of the cases Novaya Europe documented came from medium-sized towns and only rarely from large cities. The regions of Novgorod, Magadan, Sakhalin, and Kamchatka top the ranking with the highest number of deaths per 100,000 people. In absolute terms, however, the places reporting the highest number of deaths in police custody were Moscow (78 people) and the regions of Nizhny Novgorod (65), Sverdlovsk (60), and Chelyabinsk (58).

Isolation, torture, mobilisation

Russia’s criminal code was amended in 2022 to include articles making torture in police custody a crime. Since then, according to a November report by Mediazona, 32 people have been charged under the new clause, most of them police officers.

We found 18 cases in which torture was believed to have led to deaths in custody in our 2023 data — the highest number recorded in the last 14 years.

However, in some of these cases it was the lawyers or the victim’s family who suspected torture and not the authorities.

At the same time, the Committee for Civil Rights noted that the number of complaints of torture has dropped dramatically. This might be due to forced recruitment for the war in Ukraine.

Just as the Russian authorities regularly press gang immigrants and inmates into fighting in Ukraine, so those detained by the police, even for minor misdemeanours, often face similar pressure.

In June, human rights activists North Caucasus SOS reported that Chechen security forces were blackmailing detainees to enlist to fight in Ukraine, threatening them with long prison sentences and or the prospect of their relatives being sent into combat if they refused.

Stress and suicide

Not all the deaths in custody that our research documented can be ascribed to police violence, of course, sometimes the stress of detention, a lack of necessary medications, or intoxication can prove fatal. But it’s impossible to estimate the number of such cases based solely on news reports.

Public access to both police stations and pre-detention centres in Russia is highly restricted. Our research has shown that most disclosed deaths occurred in police stations, accounting for over half of our sample, or 588 people.

A further 281 people died in pre-trial custody. Nearly a fifth of our sample, or 262 people, died in various types of detention centres. A further 199 people died while being transported by the police, in hospital immediately after a visit to the precinct, or in a courtroom.

The reported causes of death range from heart attacks and epileptic fits to “failure to wake up” or “injuries resulting from a fall from the top bunk”.

Police stations have an abnormally high death rate from heart failure, heart attacks, injuries, and suicide. In police stations, people are much more likely to die of natural causes, mutilate each other, or hang themselves by their shoelaces and belts, which the police are supposed to take away.

At least a quarter of those who committed suicide in detention according to our data had been arrested for minor administrative offences such as disorderly conduct or for being intoxicated in public.

Experts interviewed by Novaya Europa agreed that there was no correlation between torture and the gravity of the suspected offence. In other words, anyone can face torture while in police custody in Russia, it’s more often than not a case of being “in the wrong place at the wrong time”. The torturers have a very primitive motivation — to “solve” crimes faster and reach their case quotas, says Sergey Babinets.

Official causes of death are easy to fake and difficult to refute. Cardiovascular disease, for example, may be the leading killer in Russia, accounting for about 40% of deaths among men of working age. However, heart-related deaths account for over 80% of illness-related deaths in detention, making them twice as prevalent in police stations than in the general population.

In the summer of 2018, 17-year-old Ilya Torokhov was detained on suspicion of stealing a cell phone. According to the police and the Investigative Committee, the teen had behaved in an unruly manner and had to be handcuffed, though they said that the cuffs had subsequently been removed.

According to the police version of events, having been left alone in the corridor to await questioning, Torokhov found an office without barred windows and jumped out, fatally hitting his head on the pavement. However, others arrested that day later said they had heard Torokhov’s screams and the sound of a beating.

Going to see his casket, Torokhov’s family took the opportunity to lock themselves inside the hall and filmed multiple injuries on his body that the forensic report had failed to disclose, including bruises to the crotch, dark yellow burn-like marks, blue ears and deep cuts to the wrists.

Members of public monitoring commissions, the civic bodies responsible for ensuring human rights are observed in prisons and police stations, are often prevented from witnessing evidence of police brutality. While they have access to such facilities without requiring special permission, as they are only allowed to visit the cells rather than the interrogation rooms in which detainees can be kept for hours at a time, they often see a limited amount.

Law enforcement rarely resorts to violence in cells and instead limits it to interrogation rooms, which become a “black hole” for all that goes on in them, says Dmitry Kalinin, formerly a member of a public monitoring commission in the Sverdlovsk region, where the number of such deaths is among the highest in Russia.

In our sample, 118 people died in interrogation rooms. Perhaps surprisingly, of these, a third were police officers themselves, most of whom committed suicide.

Suicides represent another “invisible” category of the dead: records of police deaths are also not disclosed to the public.

In fact, hundreds of police officers commit suicide every year, according to law enforcement experts, and these are most typically blamed on clashes with superiors and excessive workloads. Using open sources, Novaya Europe found at least 70 cases of police officers who died in their own police precinct over the past 14 years.

Silence as a solution

In 2011, as part of an extensive reform package, the Russian Interior Ministry ended its use of so-called drunk tanks. The initial plan was for responsibility for dealing with severely intoxicated people to pass to the Health Ministry, but this never came to pass. As a result, the police remained responsible for dealing with cases of severe intoxication, but in the absence of drunk tanks, which always had a doctor present, they were now placed in police stations, where typically no help is available in case of a medical emergency.

Even our incomplete data shows how the abolition of drunk tanks affected the death rate in police custody. By 2015, four years after the decision, there had been a sixfold rise in such deaths.

In 2016, the number of deaths reported by the Interior Ministry suddenly dropped sharply. Apparently, the “sudden” deaths were becoming too noticeable and the authorities decided more needed to be done to conceal them. Nevertheless, experts say there have been no positive results from this particular reform.

One of the stated aims of the police reforms was to earn public trust through transparency. But, as it turned out, in the words of Babinets, “showing the public that your police stations are full of torture and people dying … rather defeats the point”.

Crime yes, punishment no

Alongside the surge in sudden custodial deaths, last year saw a decrease in the number of criminal cases brought against police officers for abuse of power using violence, the umbrella term given to police brutality.

While human rights activists do say that overall the levels of brutality inflicted in police violence has decreased in recent years, another equally alarming practice has emerged to conceal the tell-tale signs of abuse that does still go on, a member of the NGO Committee for Civil Rights told Novaya Europe. Detainees are remanded in custody at a police station for the legal limit of two days, then they are sent to a detention centre on a trumped-up administrative charge, allowing investigators time to fabricate a more serious case, and ensuring detainees are not able to see family members or their legal representatives while they do so.

Even when there is evidence, getting a case into police violence opened remains a challenge. The only cases that tend to go to trial are those that have been publicised by the media to the extent that not investigating it could pose its own consequences. If found guilty, the accused is likely to face a harsher sentence in such cases too as they are made an example of.

The Crew Against Torture says that on average it takes three years and six appeals to get such a case opened, adding that only 45% of complaints ever go beyond the initial investigation stage.

Following the 2002 death of Zhavdat Khairullin in a Tatarstan police station, for example, the case was opened and closed more than 20 times as investigators continued to find no corpus delicti. In the end, the corpus delicti was established by the European Court of Human Rights, which ordered Russia to pay €48,000 to Khairullin’s widow in 2017, 15 years after the incident.

In the years immediately preceding Russia’s withdrawal from the Council of Europe in 2022, more cases were referred to the European Court of Human Rights from Russia than from any other country, most of which involved allegations of torture.

Almost half of the sentences in the resulting cases were suspended. Another third resulted in fines. Those sentenced to prison received the shortest possible terms — 3.5 years on average.

As lightly as police officers currently get off, their chances of acquittal or receiving a very lenient sentence are likely to be even greater if they’re veterans of the war in Ukraine. Since 2018, Russian courts have handed down sentences half the length of those issued for other fatal torture cases if the culprit was deemed to have been of “merit to the homeland”.

“War veterans are rewarded for the use of violence and achievements in combat: they are given medals, money, and a pat on the shoulder. The idea that violence is approved behaviour begins to take root in their heads,” says Babinets.

“And when these people, including those with PTSD, injuries, and disabilities, return to civilian life, law enforcement will be the first place for them to find employment.”

Written with the help of Rufat Mustafaev

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]