Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused the largest wave of immigration in decades. The exact number of those who fled is unknown, but independent researchers report that about 800,000 Russians could have left the country in 2022. Among the most popular destinations are Kazakhstan, Armenia, Turkey, and Georgia. Surprisingly, the United States is among them too.

A Russian citizen can enter the US legally, for example, with a tourist visa. But for the past several years it has not been possible to issue it in Russia. Amid the conflict with the Russian authorities, the US Embassy in Moscow no longer provides these services. However, there are other legitimate ways. For example, to ask for political asylum in the transit zone.

Most often, people request it on the US southern border. In the last fiscal year alone, more than 21,700 Russians were stopped while trying to enter the United States from Mexico, and as many as 25,000 were turned away within five months after the start of “partial” mobilisation. Whereas in 2021, there were only 4,100 such cases.

Since the Russians usually do not have a US visa, officers detain them, charge them with illegal border crossing, and launch expedited removal proceedings. But the final word is up to the Immigration Court. If a person is granted asylum, they have the right to remain in the US and apply for permanent residence and citizenship in the future. If not, they might face deportation.

In an exclusive feature for Novaya Gazeta Europe, former Novaya Gazeta special correspondent Elizaveta Kirpanova shares her personal experience of going through this tough immigration process.

Mexico City, the capital of Mexico. Photo courtesy of the author

Prologue

On 21 March 2022, my husband Georgii Manucharov and I fled Russia. We took two suitcases with essentials (one of them was left behind on the way) and flew first to the United Arab Emirates, then to Armenia, and a couple of weeks later to Mexico. In Mexico City, we boarded a flight to Tijuana, a city that borders San Diego and is officially considered the most dangerous in the world.

In addition to the bloody clashes between cartels, tourist kidnappings and murders, drug and alcohol trafficking, Tijuana is well-known for immigrant smuggling to the United States. The US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is trying to prevent desperate asylum seekers from crossing the border in illegal places (all of them are well known to the guards). Despite the right to request asylum and to be admitted to the US, these people are often detained and deported back to Mexico. Immigrants from Latin America are those who face it more than anyone.

The border city of Tijuana. Photo courtesy of the author

The formal excuse for deportation was Title 42 — a rule that since 2020 has been actively used by the administration of former US President Donald Trump. It allowed CBP officers to turn away and deport immigrants without explanation under the guise of combating the spread of COVID-19. This controversial rule ended in May.

We chose another, safer and at that time more legal, way to request asylum — at the official port of entry. There are two of them in Tijuana: San Ysidro and Otay Mesa. Asylum seekers could not come there on foot (the exception was the Ukrainians, who also crossed the border here for the first few months after the war began, but on the grounds of humanitarian parole).

People who tried to pass officers on a bicycle and a motorcycle were not allowed. There was only one option left: to drive up by car.

There are countless sales ads for used cars in Tijuana. We quickly found and bought a cheap Subaru and drove it to the border the next morning. It was necessary to show the officers a driver’s license (at this stage, it was not required to show a visa or its absence) at the entrance to the first line of the port of entry in Otay Mesa. But the guard, seeing that my husband's driver’s licence was Russian, forbade us to proceed further. After a couple of hours, we made a second attempt. This time Georgii's Russian license did not confuse anyone, and our car was admitted to the booths with officers checking documents. We asked them for political asylum and handed over our passports. After that, our car was sent to a parking lot, and us — to a CBP’s admissibility enforcement unit. We spent almost a week in AEU’s tiny, packed, and cold cells. From there, handcuffed, we were transported to an immigration detention centre in Louisiana. I spent nine days there, Georgii — three weeks. You can read more about our detention in the first part of my reporting.

The border city of Tijuana. Photo courtesy of the author

Later, when I was paroled into the US, I learned that until the end of last year, “legal services” for border crossing were also provided by organisations that claimed to be charitable foundations. They promised asylum seekers a “green corridor” into the US without spending money on a car and going to jail. For a certain “donation”, volunteers arranged for Russians a meeting with CBP and accompanied them to the port of entry at the appointed time. After the interview and filling out all the paperwork, the officers assigned the immigrants a court date and admitted them to the US.

Now it is impossible to cross the border neither “through a hole in the fence”, nor with the help of foundations, nor by car.

In January 2023, the administration of President Joe Biden announced that from now on the only legal way for asylum seekers to enter the United States would be via the government's app called CBP One.

A person can now make an appointment with an officer only if they are physically present in Mexico. Meanwhile, immigrants complain the app is buggy and often crashes. People are stuck in Mexico for weeks or even months waiting to arrive on the US soil. Shelters are overcrowded, spontaneous tent camps appear along the southern border. Local human rights activists report with concern about the growing humanitarian crisis.

A fence in Tijuana separating the US and Mexico. Photo courtesy of the author

Georgia

To get out from the AEU or detention centre, an asylum seeker needs a sponsor. It can be any US citizen or permanent resident. In our case, it was Georgii's great uncle, who came to the US around 15 years ago and later obtained an American passport.

The officers contacted him after they detained us using the number we had put in our passports in advance (and remembered by heart in case the piece of paper got lost or fell out). They asked my husband’s uncle if he really knew us and was ready to accommodate at his home, at least initially. He agreed. This was the key factor to our release.

On the way to the airport after leaving the Louisiana detention centre. Photo courtesy of the author

Not all asylum seekers have relatives and friends in the United States. Messages from people searching for a sponsor regularly slip through in immigrant chats. They often add there is no need to provide them with housing or other assistance. Demand creates supply, and now, along with such requests, one can also find advertisements of paid “sponsorship”. Such people, among whom there are also scammers, promise to answer the call from the border officer for several hundred dollars. These “services” are illegal, but it doesn’t stop desperate asylum seekers.

I know people who have negotiated sponsorship with a stranger on the Internet who simply did not pick up the phone. As a result, they spent a much longer time in jail than they expected.

If they had not found a new sponsor, then most likely they would have stayed in the detention centre until the court hearing.

According to the rules, after jail we had to go to our sponsor. But staying with him was not necessary: no one forbids you to change the address and move, for instance, even to Hawaii. The only important thing is to warn all immigration authorities.

A typical small town in Georgia. Photo courtesy of the author

Our sponsor lives in Georgia — an agricultural state in the southeastern part of the US. It produces peanuts, pecans and peaches: Georgia’s officially nicknamed the “Peach State”. The region has a complicated, in many ways tragic history. Formerly a slave state, Georgia was one of the Confederate centres during the Civil War. This period is a core theme of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “Gone with the Wind” written by Margaret Mitchell, who lived in Georgia. It is also the home of Martin Luther King, leader of the black rights movement and Nobel Peace Prize winner, as well as world-famous singer and pianist Ray Charles, whose hit “Georgia on My Mind” is the state's official anthem.

The capital of Georgia is bustling Atlanta with a population of almost half a million people. Here you can find the largest aquarium in the country, the Coca-Cola Museum (the soda was invented here) and the CNN headquarters. The city resembles New York with its glass skyscrapers. Many of the Marvel blockbuster scenes set in the Big Apple were shot in Atlanta. Filming is constantly taking place in the city centre and its suburbs, which is why the capital of Georgia is often called the “second Hollywood”.

In the hallway of the CNN headquarters. Photo courtesy of the author

We settled in a quiet suburb half an hour from Atlanta. Though we didn’t have much of a choice in the matter: we were lucky to have everything set up for us already.

My parents, who requested asylum in the US six months earlier than us, found the house where we live right now. They were lucky to rent it in a prosperous area, although it was not easy. Their passports were retained at the border in the same way as ours. Without documents it is very difficult to immediately issue a Social Security Number —a taxpayer identification number that is even more important than a passport in the US. Without an SSN, in turn, you cannot get a credit card and start building a credit score.

This is the main indicator of solvency and the first thing American homeowners look at. Fortunately, we found a Russian-speaking landlord who agreed to help my family.

Our house — half red brick, half beige siding — has two floors. On the ground floor there is a large living room which goes into the kitchen and dining area, a two-car garage and a couple of storage rooms. On the second floor there are three bedrooms, two bathrooms and an alcove with a washer and dryer. The floor is covered with a typical American grey carpet, the walls are plain white and beige. You can’t repaint them or, for example, hang shelves without the landlord’s permission. You can’t change the house exterior either without the approval of the subdivision's Homeowners association. Want to paint your fence yellow? You’re not allowed, because all fences must be in the same style: wooden and unpainted. You shouldn’t neglect the house lawn either: if you don’t cut the grass regularly, be ready to pay a fine.

A clubhouse and a common area in a subdivision near Atlanta. Photo courtesy of the author

We rent a house for an exorbitant price by Russian standards — $2,500 per month (this does not include the cost of gas, water, and electricity). It was traditionally rented empty. However, it was not difficult to acquire all the necessary household items for free. The Americans often move, but rarely bring furniture to another house because moving is expensive. It’s easier to buy new one, and sell the old (this does not mean bad) cheaply on Facebook Marketplace or simply put it in front of the house so that whoever wants it could take it for free. That’s how we got three decent sofas, a large dining table and chairs. We recently started inviting guests over. Now they finally have something to sit on.

The rental price includes free use of basketball and tennis courts and a swimming pool located on the territory of our subdivision. On summer weekdays, there is almost no one there. But on weekends all the chaise loungers are full. In addition to the traditional beach attributes — towels and inflatable swim rings — the Americans bring portable coolers with food and drinks, which they usually take on a hike, music speakers and barbecue grills.

Tennis court in a subdivision in Atlanta suburbs. Photo courtesy of the author

Attorney

The first step towards legal asylee status is to file Form I-589. This is an official application for asylum and withholding of removal. It must be submitted within one year after entering the US. Many fill out the form themselves or with the help of a paralegal because it is cheaper than hiring an immigration lawyer. Prices for paralegal services start at an average of $400 per person. But I decided to work with an attorney from the very start till the last court hearing.

How to find a good lawyer? It’s a difficult question. In my opinion, it is important to choose a specialist in the state of residence, since different judicial districts have their own immigration nuances. Now I know that the lawyer’s ratings and reviews can be checked via private services like Avvo. But I myself skipped that part and trusted our sponsor, who recommended Carolina Antonini from Antonini and Cohen Immigration Law Group as “the best lawyer in Atlanta”.

The building where Carolina Antonini’s office is located. Photo courtesy of the author

When we called the firm to schedule a consultation, it turned out that the nearest free time slot would be in a month. But if one of the clients cancelled or rescheduled the meeting, then I would take their spot. And that’s exactly what happened. A week later, I was already on my way to Atlanta for a preliminary conversation.

Consultations with most lawyers are paid, about $200-350. This money can be deducted from the total cost of legal services if the lawyer decides to take on your case. They can easily refuse, for example, if they realise that the client is lying or if they have a “weak case”.

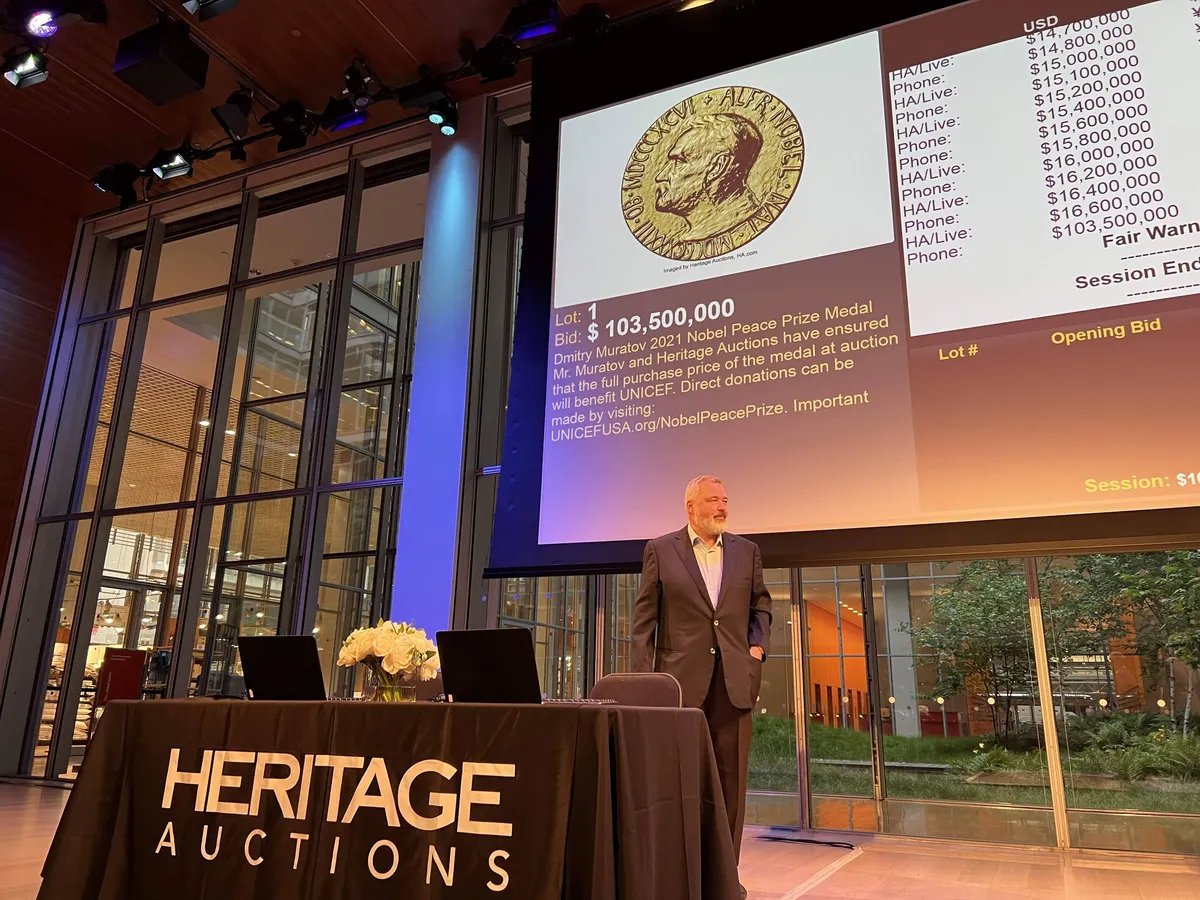

Novaya Gazeta editor-in-chief Dmitry Muratov at an auction in New York where he sold his Nobel Peace Prize medal for $103.5 million in support of Ukrainian child refugees. Photo courtesy of the author

At the meeting, Carolina first asked what I did in Russia for a living. I briefly told her the history of Novaya Gazeta and the obstacles my colleagues and I faced while doing our job.

I remember how she opened the newspaper's Wikipedia article and was very surprised to see the names of two Nobel laureates at once involved in its foundation.

Attorney said that I had reason to apply for asylum due to the persecution for my political opinion and membership in the social group “independent journalists”. Following the consultation, Antonini agreed to defend me in court.

Hiring a lawyer cost us about $10,000. The payments were split over the next several months. This money came from the sale of my parents’ apartment in our hometown city Rybinsk (Yaroslavl region, Russia) in 2021. It's strange now to remember how I planned to invest half of it in a Moscow mortgage and how these plans changed dramatically in just a few months.

The asylum process, as Antonini explained, consists of two stages. The first is the Master Hearing. It's mostly administrative: the Judge meets the asylum seeker and finds out if he filed or plans to file Form I-589. As a rule, if the applicant has a wife or husband and children under 21, he submits the form, including his family members as derivatives. He is granted asylum — the rest automatically too.

It is mandatory to be present at the first hearing, otherwise the judge can decide to deport the person in his absence. Sometimes asylum seekers miss it unintentionally due to the fact that not all officers inform applicants when they will have their hearing after being released from the border or detention centre. When there is no exact date, applicants are advised to check their case status on a special website. The waiting time can be very long. After a few months without any changes, many applicants begin to check the hearing date irregularly, if not completely forget about it. And when they finally decide to do it, it turns out the hearing has already taken place. Without them.

A Friday night in Atlanta suburbs. Photo courtesy of the author

At the Master Hearing, the judge must set a date for the Individual Hearing. It’s when the applicant's case is examined on the merits and a decision is made whether or not to grant them asylum. If the applicant does not have a lawyer at the time of the first hearing, the judge will most likely set them another preliminary meeting.

My first hearing was scheduled by CBP officers for September 2022. In July, Carolina filed my I-589 form in advance. After that, bypassing the Master Hearing, I was immediately set for the Individual Hearing in April 2023. That was very fast.

But it was not without difficulties. When I applied for asylum, Georgii’s case information, for some reason, had not yet appeared in the court system.

Simply put, it meant that the deportation process for us so far proceeded independently of each other, as if we were not married.

This had its pros and cons. If I had won the case and been granted asylum, Georgii would have been able to obtain the same status only after the approval of the Asylee Relative Petition, which now takes from one to two and a half years to process. This would significantly delay his legalisation. But if I had lost the case, then we would have a second chance to get asylum. We could file I-589 again, but this time Georgii would be the main applicant.

What happened to us was neither of these scenarios. Georgii’s case appeared in the court system in September last year. We found out about it four days before his Master Hearing. At the hearing, which took no more than 15 minutes, our cases were merged. If I hadn’t checked the case status every two days, we could have easily missed the hearing. This could have led to my husband’s deportation.

Near the Atlanta Immigration Court building (on the left). Photo courtesy of the author

Work

Georgia has quite a big Russian-speaking community. The largest immigrant Facebook group now has over 12,000 members. But there are not so many asylum seekers among them. This is because Georgia is a “purple” state.

If you look at the state’s 2022 Midterm Elections map, you can see that in the major cities of Georgia — Atlanta, Augusta and Savannah — the Americans predominantly voted for the Democratic Senate candidate. However, the rest of the territory was dominated by Republican supporters, who traditionally advocate stricter immigration laws. This is why Georgia is one of the “toughest” states to get asylum. According to the TRAC Immigration project, the average denial percentage among Atlanta judges is 94%. Judge Philip Barr, who was assigned to my case, had a 9.3% approval rate: the second highest. Few people go to Georgia considering these statistics. However, it is worth mentioning that most of the negative decisions were ruled on immigrants from Central America: El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. It is much more difficult for them to prove persecution for political reasons.

Downtown Atlanta. Photo courtesy of the author

My husband and I received our work permits this year in February. Georgii, who has an acting degree, is taking his first steps in the film industry. He has already starred in several TV series and films. These were small background roles without lines. They are paid at a minimum wage, but this is just the beginning. He recently joined a rock band that is preparing to give its first concert. At the same time, in order to pay for bills, he works in delivery, as a barista in a coffee shop and does house repairs.

I also had to plunge into something completely different from my specialisation. Now I work in an automotive shop run by five Turkish brothers who immigrated from Russia in the 2000s. I am gradually mastering the world of car parts, and how to order them. It was difficult to find a less suitable candidate for this position, but I managed. Previously, I could not distinguish Hyundai from Honda. Now I know in detail what the suspension consists of (although only in English). This job allowed us to pay off all our debts and buy our first car.

Elizaveta at work. Photo courtesy of the author

There was no time left to fully get back into journalism. I threw all my resources into carefully preparing for the hearing. I honestly do not understand when asylum seekers, after filing Form I-589, cease to be interested in their case, letting it take its course. They frivolously think that now the responsibility for the case lies entirely on their attorney. But they need to understand that lawyers are people too. They make mistakes and cannot always regularly track the status of all the documents, especially if they have hundreds of clients. In addition, a lawyer does not have the right to describe clients’ persecution for them.

Articulating the story, requesting testimonials, finding media articles, picking up photo evidence — that’s the job of the asylum seeker.

I know two Russian-speaking brothers who, by the time of their final hearing, had as evidence only one page of the same testimony for two. They simply forgot about the rest of the documents the lawyer had asked them to prepare. Their final hearing eventually had to be postponed.

I worked on my case every day, without exaggeration. I translated all the evidence myself, added it to my case as we went along, regularly read Russian and American news, monitored blogs of other lawyers for changes in immigration laws, looked through immigrant Telegram chats daily for useful information. I also worked on my business English because I didn’t want to use an interpreter in court. I heard they often translate the defendants’ testimony incorrectly. I couldn’t take a risk: the fate of the whole case may depend on any misunderstood word.

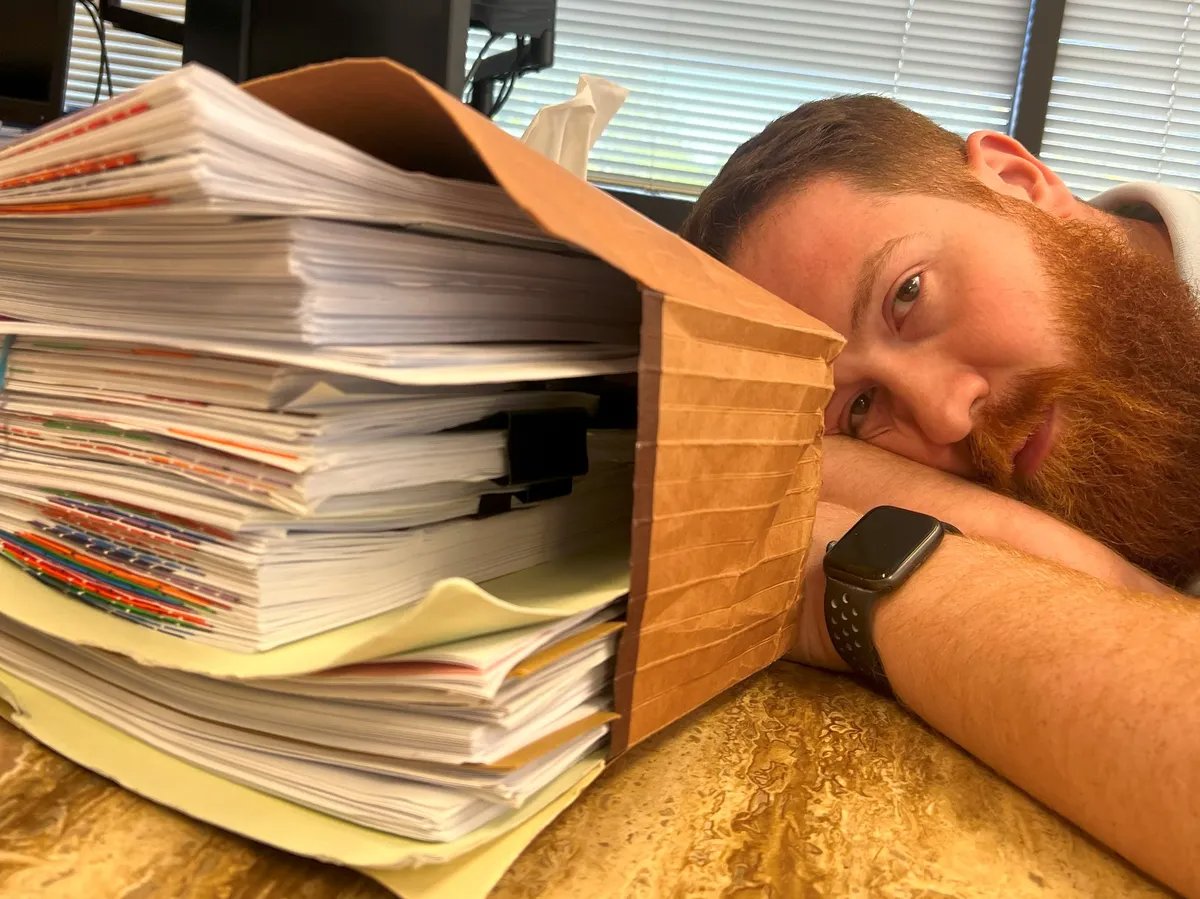

Elizaveta and Georgii’s case file. Photo courtesy of the author

Court

In January, I found out Philip Barr, the Judge assigned to me, had retired. My case was transferred to Suzette Smikle. Since she was appointed as an Immigration Judge only in October 2022, there were no statistics on her cases. I learned from the official biography that Smikle earned a Juris Doctor from Harvard Law School in 2002. For the past 12 years, she has served as an assistant US attorney first in Georgia, then in Florida. Over the years, she temporarily worked as a Resident Legal Advisor for the American government entities in Burundi, Niger and Peru.

A few days before my Individual Hearing the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) contacted Judge Smikle. The state prosecutor offered to dismiss my case “in the exercise of its sole and unreviewable prosecutorial discretion”.

According to the Department, due to changed circumstances, “continuation [of my case in court] is no longer in the best interest of the government”.

In simple terms, it meant that if the Judge approved this motion, my husband and I would no longer be in the removal proceedings, which is good. But at the same time, we will not get any legal status, and this is a problem. To solve it, we would have to re-submit the I-589 form: not to the court, as before, but to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The agency would have to schedule an interview with the officer who might have made the decision on asylum. If it was negative, we would be placed in the deportation process again. But at the same time there would be a second chance to prove our persecution in immigration court.

The prosecutor, contrary to the recommendations, did not inquire about my position on the dismissal of the case before sending the motion to the Judge. My attorney and I were against granting it: the waiting time for an interview at the USCIS could take up for years. In the opposition letter, Carolina Antonini emphasised that the DHS has failed to establish that circumstances in my case have changed and to demonstrate that continuation is no longer in the government’s best interest. One of the reasons for exercising “prosecutorial discretion” is usually the desire to use “limited government resources” more efficiently. However, in our case, the lawyer noted, dismissal of the case would have led to the opposite result. If the prosecutor’s motion was approved, we would have appealed this decision, which could have led to an additional burden on both the judicial system and the DHS itself.

A few days later, the prosecutor sent another letter to Judge Smikle, informing her that he did not intend to appear at my hearing at all. At the same time, the Department opposed the grant of asylum. However, he would not appeal if the Judge’s decision was positive. According to Antonini, the judge said the DHS was “wrong to ask for dismissal [of the case] and then ask for a denial without even hearing evidence or testimony” of the defendant. We expected Smikle to make the decision whether to close my case or not right at the hearing.

Near the court building. Photo courtesy of the author

20 April was a sunny day in Atlanta. An hour before the hearing, we drove up to the Immigration Court, which is located in the very city centre in one of the glass skyscrapers.

Dressed in brand new suits, bought specifically for the hearing, we felt like we were about to take an important university exam. Only instead of study materials, we should be tested on the facts from our own lives.

We entered the court at precisely 1 PM. A small room with grey walls was divided into two parts by a railing. The large wooden benches for spectators in the first section were empty, the second part had tables with microphones for prosecutors and defendants. In the centre was the Judge’s desk with two large monitors. Behind it — a TV screen in case one of the parties cannot be present offline.

When Judge Smikle entered the room, we stood up and, at her invitation, walked behind the railing to our table. After discussing formal issues with the lawyer and connecting Georgii’s online interpreter, the judge asked us to take an oath. We raised our right hands and promised we would speak truth and only truth. Then I moved to a separate table to testify. Before I began, the Judge warned me that during the interrogation she might not always look at me, rather than type on the computer, but this did not mean she was not listening to me.

Antonini asked me questions first. Her task was to reveal the essence of my case. By law, in order to be granted asylum, I must have proved either that I have been systematically persecuted by the government in the past, or that I have a well-founded fear of future persecution.

A severed ram’s head sent to the Novaya Gazeta office with a threatening message

What I told the lawyer

In response to Antonini’s questions, I talked about the events that occurred in Russian journalism and in my life as a reporter over the past five years. Among other things, I mentioned how:

- In 2018, a funeral wreath was left in front of the Novaya Gazeta’s building with threats to my colleague Denis Korotkov, who was preparing an investigation about head of the Wagner Group Yevgeny Prigozhin. After that, Novaya Gazeta received a severed ram’s head with threats against the entire editorial office, and some time later — three cages with sheep dressed in “Press” vests. This happened at the same time as the school shooting at a college in Kerch. On that day, I collected comments from eyewitnesses and published an article that was discussed on air on Russian propaganda TV. The propagandists named the author of the text (who was me) “an accomplice of information terrorism” and said that there should be a punishment for journalists who “spread panic”.

- In 2021, Russia’s National Guard beat me and my colleagues while covering a rally in support of oppositionist Alexey Navalny. This incident was reported by almost all independent Russian media and many foreign media. “Reporters Without Borders” even called on the European Union to impose sanctions against those responsible for our beating. However, the perpetrators have not yet been identified. The police decided not to open a criminal case, publicly stating that the police check did not reveal any of our injuries. A few weeks after these events, our office was under a chemical attack. The smell of a toxic substance spilled by an unknown person in the courier uniform was so pervasive that the editorial office had to change the asphalt around the main entrance. The perpetrator was also not found.

- In 2022, Novaya Gazeta faced unprecedented pressure from the Russian authorities for its coverage of the war in Ukraine. Millions in fines from Russian media watchdog Roskomnadzor, labelling my colleagues as “foreign agents”, new criminal cases, attack on the editor-in-chief and Nobel laureate Dmitry Muratov. Last March, the editorial office had to suspend operations, and in February 2023, the authorities took away our media license for good. For publishing several articles, we have been fined under the recently passed law on the “discrediting” of the Russian military. Most of our journalists now live in exile.

- I was also talking about colleagues from other media outlets facing political persecution. First of all, about RusNews journalist Maria Ponomarenko, who was sentenced to six years in prison for a post about an artillery attack on a theatre in Mariupol, and about WSJ correspondent Evan Gershkovich arrested in Moscow on charges of espionage for the United States.

Decision

The DHS was supposed to ask me questions after the lawyer. But the prosecutor, as he warned in advance, did not appear at our hearing. Judge Smikle began the interrogation then. Since it was forbidden to record the hearing, I cannot quote her questions verbatim. I can only mention some of them that I remember by heart.

Speaking about the 2021 protest in support of Navalny, the Judge asked if the guards who staged the attack knew me. I did not understand this question the first time. Of course, they knew that I was a journalist: I was wearing a bright press vest and a badge around my neck with my name and occupation. They also understood that I was an independent journalist, because state media correspondents had long ceased to officially cover unauthorised rallies. Then the Judge asked again: did the police know me personally? The answer was no.

A protester sanitising Elizaveta’s head injury after she was hit with a baton. Photo courtesy of the author

Have there been other physical attacks on me personally and have I personally received death threats? I remembered the threats left on my social media in 2019. After covering protests in support of honest elections to the Moscow City Duma, my Instagram was attacked by bots.

Among the comments they left under my photos were: “Where is the government looking? Such degenerates should be imprisoned” and “You’re dumb. Prison is calling for you”.

Have I contacted the police about these comments? I didn’t expect this question. Russians often do not go to law enforcement agencies even with more serious threats. I told the Judge I had not asked the police for protection.

Have my colleagues personally received death threats or been physically attacked? I answered yes, but I couldn’t give specific examples. Despite the fact that half an hour ago, during the lawyer’s interrogation, I mentioned the attack on Dmitry Muratov on the train. And despite the editors regarding the wreath, the ram’s head and the cages with sheep in 2018 as threats as well, which I also spoke about earlier. I am ashamed that I did not tell the Judge about the six murdered Novaya Gazeta’s journalists. By that time, the hearing had been going on for almost three hours. I was terribly anxious and felt sick after spending so much time in a stuffy room. Only illegal fines, arrests and criminal cases under the article on “discrediting the army” popped into my head. I talked about them in detail again.

Novaya Gazeta editor-in-chief and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Dmitry Muratov right after the attack when an unknown man threw red paint on him. Photo: Dmitry Muratov / Novaya Gazeta

After the interrogation was over, Carolina Antonini made the final statement. In her speech, she mentioned the case of Cuban journalist Luis Martinez. He wrote critical articles for a dissident online periodical. Though his materials were published anonymously, the Cuban authorities were able to figure out Martinez’s identity. Government officials beat the journalist unconscious on the street, arrested him twice and held him in prison without filing any charges. They also forbade him from leaving the country. The Immigration Court of Atlanta denied Martinez asylum. According to the Judge, the authorities suspected Martinez of “merely associating with journalists”, and there was no direct evidence of persecution for his journalism. In 2021, the Atlanta-based Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the previous decision was erroneous mostly because the persecution of other dissident journalists in Cuba had been well documented. The case, according to Antonini, showed that it is not necessary for an applicant to prove that they personally faced threats if there is a “pattern of practice” of persecuting members of the same social group. This practice, the lawyer noted, is also applicable to my case.

Judge Smikle listened carefully to my attorney, and then, without going on a break, announced that her decision was ready. For the first criterion — past systematic persecution — the judge denied me asylum. She considered the episodes I described not threatening my life and health, and the injuries received during the protests in 2021 not serious. However, the judge took into account the current situation in Russia in relation to my social group — independent journalists. She acknowledged that my fear of future persecution if I returned to Russia was well-founded.

“I grant you asylum,” declared Judge Suzette Smikle.

After that, Georgii tightly squeezed my hand. Carolina and I breathed a sigh of relief. Tears came to my eyes.

Elizaveta, Georgii, Carolina. Photo courtesy of the author

Epilogue

More than two months have passed since the final hearing. There is no more fear of deportation, but there are other things to worry about. We need to save money to apply for permanent residence. As it turned out, it is not cheap: a fee for one person is $1,225. We do not expect to obtain it quickly. The waiting time for a Green Card is expected to be one to three years.

Now that there is more certainty in our lives, we even dare to dream.

We dream of finally making a long-planned trip from the east to the west coast of the United States, visiting all our friends and relatives along the way.

We dream of seeing those who remain on another continent, who were separated from us by war.

We dream about simple things: our own house, children, and a dog.

In Atlanta. Photo courtesy of the author

Georgia, United States

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]