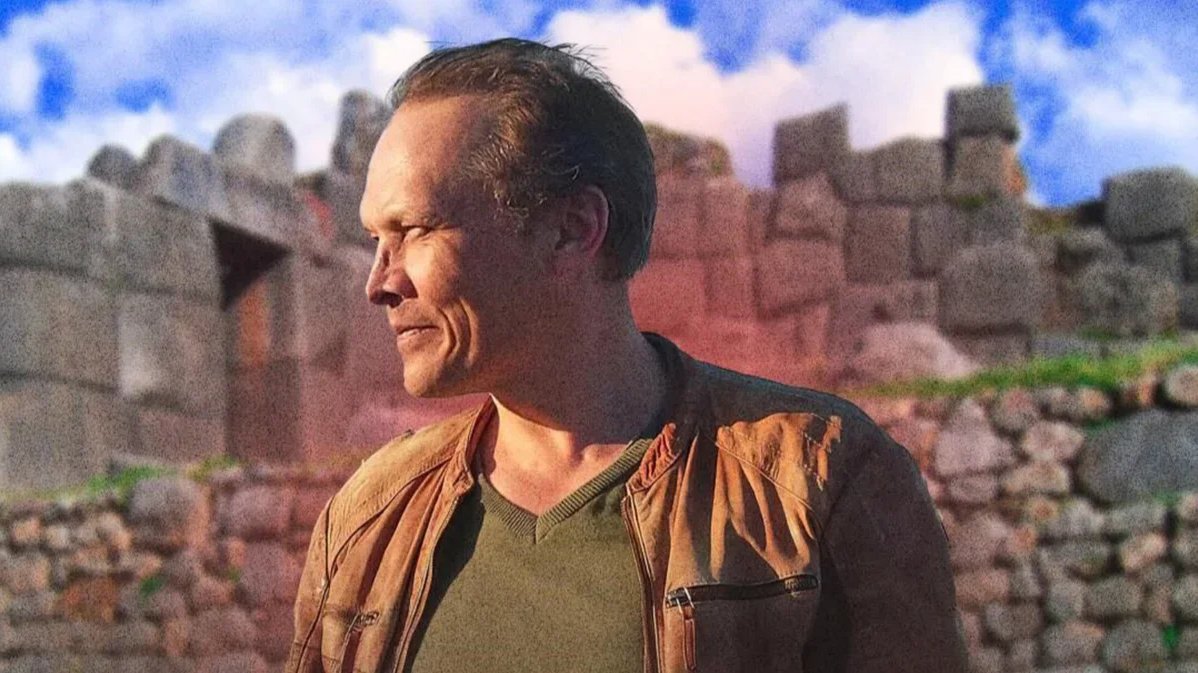

At the end of May, Russia’s latest treason trial reached its conclusion. This time, the person being convicted behind closed doors was Andrey Veryanov, a 55-year-old self-taught scientist and archaeologist who has spent much of his adult life in Peru. Nothing about Veryanov is ordinary: not his case, not his backstory, and certainly not his 24-year sentence to be served in a maximum-security penal colony.

Veryanov built a successful business, worked on geological expeditions, and made several notable archaeological discoveries during his time living in Peru. In 2017, however, he decided to return to his homeland. Five years later, when the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine began, Veryanov made his opposition to it well known, attending protests, fiercely criticising the Kremlin on social media, and continuing to associate with people labelled “foreign agents” or “extremists” by the Russian authorities. While doing so, according to investigators, Veryanov supposedly invented a device made from tin foil and cardboard which interfered with Russian air defence systems.

Before long, Veryanov was detained, heavy-handedly and publicly, after which he was placed in pretrial detention in Moscow’s infamous Lefortovo prison, assigned a lawyer by the state, charged with treason and — eventually — convicted in a “classified” trial conducted entirely behind closed doors.

Veryanov had been staunchly anti-Soviet, making friends with foreigners and trading their valuable currency and fashionable clothes, both of which were in short supply in the USSR.

In addition to the treason charges, Veryanov was charged with participating in the activities of a terrorist organisation for allegedly attempting to join the Freedom of Russia Legion, a volunteer unit of Russian citizens fighting within the Ukrainian Armed Forces that was classified as a terrorist organisation by the Russian government in 2023.

Veryanov was found guilty on both counts. What follows is what we know about the self-taught geologist who has become one of the most unusual figures ever to be convicted of treason in Russia.

Andrey Veryanov with two Peruvians. Photo: Facebook

The outsider

Andrey Veryanov was born in 1970 in Rostov-on-Don, an important port city on the Sea of Azov in southern Russia. From an early age, Veryanov showed a capacity for independent thinking and action, dropping out of school after finishing the eighth grade, completing his compulsory military service, and eventually going to work in a Rostov helicopter factory.

In 1991, Veryanov met his future wife Diana, the daughter of a Peruvian immigrant to the USSR, at a party. Just over a year later, the pair had their first child, Alexander. Years later, his by then ex-wife Diana described him as somebody living “outside of the system” and called him an “adrenaline junkie”, adding that throughout their acquaintance, Veryanov had to be “against something” and “against somebody”.

The brutality of the siege shocked the country, and, for Veryanov, served as proof that Russia was no longer a safe place for his family.

At the time, Veryanov had been staunchly anti-Soviet, making friends with foreigners and trading their valuable currency and fashionable clothes, both of which were in short supply in the USSR. Following the collapse of communism, Veryanov began travelling to Moscow in the hopes of earning some real money. Veryanov’s business plan involved selling geodesic theodolites — high-precision optical instruments used to measure the Earth’s surface — to customers in Latin America. The venture did not take off.

In 1993, Veryanov moved his family to Peru. There, he again tried to sell theodolites, again, without success, and before long the family returned to Russia. By then, Veryanov had learned to speak Spanish fluently and began working as a translator.

Things continued this way until 2004, a year described by Veryanov in his letters sent from Lefortovo as a “watershed” moment in his life. In September of that year, in the Caucasian republic of North Ossetia-Alania, armed militants stormed School No. 1 in the town of Beslan, taking more than 1,000 people hostage, most of whom were children.

The crisis, which lasted three days, ended with a botched rescue operation by the Russian security forces that resulted in the deaths of over 330 people, including 186 children. The brutality of the siege shocked the country, and, for Veryanov, served as proof that Russia was no longer a safe place for his family. As a result, when his second child, a daughter, was born a year later, Veryanov once again moved his family to Peru.

At one point, he apparently even told friends that he intended to give up his Russian passport and would apply for Ukrainian citizenship at the embassy in Lima.

There, Veryanov forged a living for himself in the antique weapons trade, buying German guns and other military paraphernalia from individuals all over South America, a popular destination for fugitive Wehrmacht soldiers following the end of World War II. In turn, Veryanov would sell the items on to collectors from the United States.

At the same time, Veryanov also found a new calling: ground-penetrating radar surveying. Peru was experiencing a mining boom in the early 2000s, and the demand for subsurface geological analysis was growing fast. Despite having no formal training in the field, Veryanov threw himself into the work, driven simultaneously, according to his ex-wife, by his own enthusiasm and the necessity of making a living.

The Inti Raymi sun festival at the Sacsayhuamán archaeological complex in Cusco, Peru, 24 June 2021. Photo: EPA-EFE/Stringer

According to his colleagues, Veryanov was the first person in Peru to successfully undertake geophysical research using high-powered ground-penetrating radar systems. At the time, such advanced technology was virtually unknown not only in Peru, but in Latin America as a whole.

In 2012, the Peruvian Culture Ministry hired Veryanov to investigate why the giant stones making up the Inca-built Sacsayhuamán Fortress near the city of Cusco were shifting around and, in some cases, falling over. Organising an expedition of geophysicists from Russia and Ukraine, Veryanov and his team found that groundwater was increasingly washing away the structure’s foundations.

He began to abuse alcohol and cocaine, spending seven months in rehab before attempting to make a dramatic escape by jumping from a third-floor window.

Veryanov, however, also noted that the stone in the fortress walls differed in appearance from the ordinary limestone used elsewhere in the structure. None of the blocks had the characteristic veins or signs of fossilised organic life that would typically be expected in sedimentary rock, even though a sample had confirmed that the stones matched the chemical composition of limestone from a nearby quarry. So the self-taught geophysicist made his hypothesis: using an unknown technology, the Incas had taken hundreds of tons of rock, and crushed it into something resembling concrete.

The discovery, though not officially accepted by the Culture Ministry, made Veryanov a name for himself among Peruvian geophysicists, allowing him and his wife to set up their own geophysical surveying company. Their clients included major gold, copper, iron ore, manganese and titanium mining firms. Suddenly, everything seemed to be looking up.

Cracks in the surface

Russia’s illegal 2014 annexation of Crimea and the launch of its war against Kyiv in eastern Ukraine both came as a profound shock to Veryanov, who had many close Ukrainian friends. Those close to him say he struggled to comprehend the Kremlin’s actions and spoke openly of his disgust at what was going on. At one point, he apparently even told friends that he intended to give up his Russian passport and would apply for Ukrainian citizenship at the embassy in Lima, although he didn’t ultimately go through with that plan.

At the same time, Veryanov and Diana’s marriage broke down, and he began to abuse alcohol and cocaine, spending seven months in rehab before attempting to make a dramatic escape by jumping from a third-floor window. Veryanov broke his spine and both legs, leaving him confined to a hospital bed for the next few months.

It struck Veryanov that in Russia he was in the thick of things and could perhaps make a difference.

By 2016, Veryanov had once again begun travelling regularly to Russia, hoping to start a new chapter of his life and reluctant to be so far away from his elderly mother. In 2018, when Russia hosted the World Cup, Veryanov worked as an interpreter in Sochi. Then, as he had done in the 1990s, he moved to Moscow, in an attempt to make some real money.

“I assembled stages on Red Square, cleaned garages in auto repair shops, [worked] as a carpenter, at a sawmill, as a mechanic… I also worked as a Spanish translator,” Veryanov wrote from pretrial detention.

Tin foil devices dug up by FSB officers in Veryanov’s presence. Photo: FSB video screenshot

Veryanov became actively involved in politics, attending protests against the Moscow City Election Commission’s refusal to register independent candidates to stand in elections to the Moscow City Duma in 2019, and, two years later, demonstrating against the arrest of Alexey Navalny.

Then, in February 2022, Russian troops rolled into Ukraine as the full-scale invasion began. Veryanov, according to his son Alexander, was angry — both at Putin and at the Russian people for “not overthrowing their president”. He began to voice his opinions more openly online as well as in conversation with friends and acquaintances.

“When Putin started the war, I tried to resist, looking for like-minded people. I hope that this nightmare will soon be over and we will all be free.”

According to those close to him, Veryanov wanted to leave Russia again. This was another watershed moment, as this time he wanted to take his mother and sister, who lived near the border with Ukraine. But doing so turned out to be far more difficult than he had imagined, and, perhaps more importantly, it struck Veryanov that in Russia he was in the thick of things and could perhaps make a difference.

In the summer of 2023, Veryanov told a friend that he was working on launching an object that could confuse Russian air defence systems stationed at military facilities near Moscow. To illustrate his point, he linked a Wikipedia article about “corner reflectors” and sent a photo of the design he had made. He explained that upon detecting such an object, a radar would instruct air defence systems to shoot it down.

The reflector in Veryanov’s photo was attached to a bunch of white and blue balloons. He explained to his friend that it was the flag of the Freedom of Russia Legion. Whether this correspondence was ever used in evidence against him is unknown, as all judicial proceedings related to Veryanov’s case have been classified.

Andrey Veryanov in Moscow. Photo: Facebook

Fault line

In December 2023, Veryanov was detained in a dawn raid on his home in the Moscow region. In video footage that was leaked to state media, he is shown with his face blurred, being held face down on his bed by armed FSB agents as he is handcuffed. After admitting to his arresting officers that he had prepared “fireworks” at the behest of the Freedom of Russia Legion, he is led in handcuffs to a snowdrift outside, from which the FSB officers retrieve something that appears to be foil-wrapped pieces of cardboard or plywood.

Three months after his arrest, an FSB press release alleged that Veryanov had attempted to disrupt Russian air defence systems on behalf of the Freedom of Russia Legion, having “assembled and launched unmanned aerial vehicles to create decoy targets in the immediate vicinity of Russian Defence Ministry facilities”.

Much of what we know about Veryanov comes from letters he has written from pretrial detention. Last March, when the FSB press release alerted human rights activists to his existence and the criminal charges against him, they began to write to him in pretrial detention. Veryanov willingly replied, though he was careful not to go into detail regarding the accusations against him, citing the classified nature of the case.

Andrey Veryanov protesting the arrest of Alexey Navalny upon his return to Russia, 2021. Photo: Facebook

Though his letters were censored by prison guards, his political views were crystal clear: “From the moment I returned to Russia, I could not accept the nightmare into which the country had been plunged. As much as I could, I went to protests and rallies. When Putin started the war, I tried to resist, looking for like-minded people. I hope that this nightmare will soon be over and we will all be free,” Veryanov wrote.

On 23 May, after a year and a half of pretrial detention, a Moscow military court sentenced Veryanov to 24 years in prison. There is little information available about how the trial was conducted, and Veryanov’s court-appointed lawyer is subject to a non-disclosure agreement and will not answer enquiries from journalists.

Veryanov will be almost 80 when he gets out of prison if he serves his entire term.

Russian human rights organisation First Department also declined Novaya Gazeta Europe’s requests for comment, saying that it did not wish to discuss other people’s cases. Previously, however, a First Department lawyer noted that there was no evidence that Veryanov had actually been in contact with the Freedom of Russia Legion, suggesting instead that the instructions he received may have come from the FSB itself.

Memorial has included Veryanov in a list of people who have been subject to politically motivated criminal prosecution. Now aged 55, Veryanov will be almost 80 when he gets out of prison if he serves his entire term.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]