Loudspeakers in the Russian town of Ivangorod blasted victory songs across the Narva River into Estonia on 9 May for the third year in a row. On the opposing riverbank, residents of Narva, Estonia’s third largest city, populated overwhelmingly by ethnic Russians, packed together to celebrate Victory Day, watching, clapping, and waving back at their Russian neighbours.

At the same time, an Estonian government-sponsored Europe Day event, which celebrates peace and unity on the continent, began at Narva’s town hall — no more than 200 metres away. For these sister cities, 9 May, Victory Day, has turned into a battle of symbols, history, and memory, particularly since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Officials in Ivangorod first erected a stage and screens facing Narva in 2023 after the Estonian government took measures to address Russia’s lingering influence in the country.

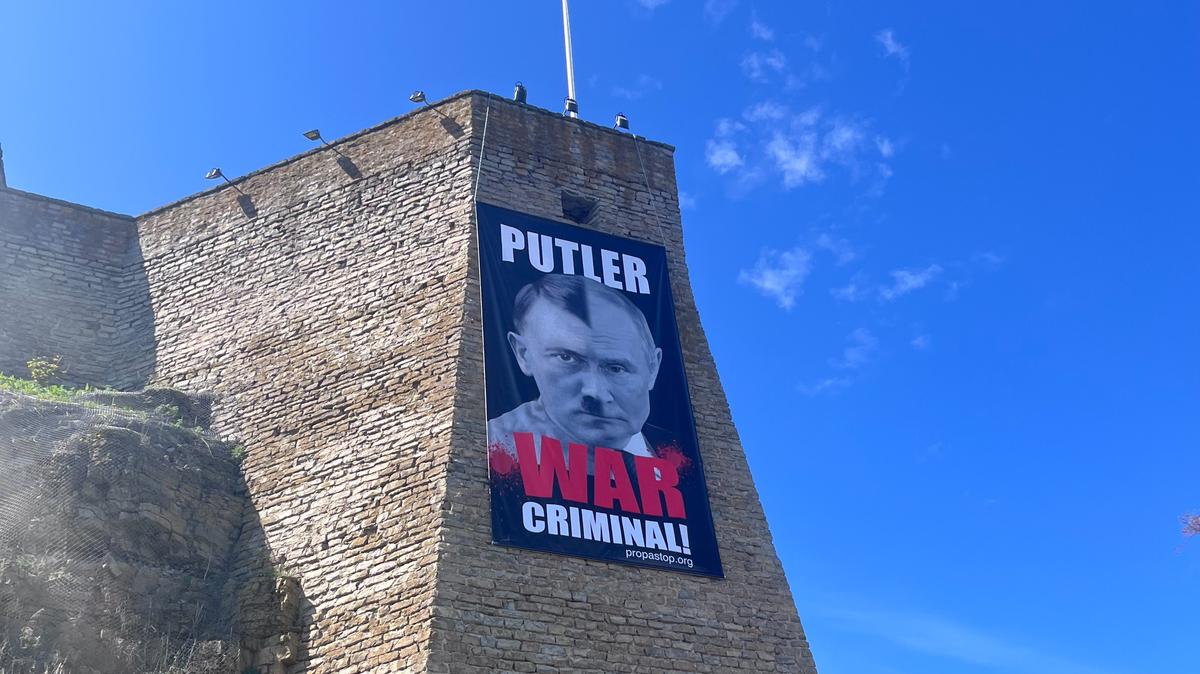

At the start of the Victory Day event in Ivangorod, the emcee welcomed his “dear friends” in the city of Narva, drawing cheers from the Estonian crowd that carried across the water. Just above their heads, a banner hung from the wall of the Narva Fortress featuring an image of Vladimir Putin and Adolf Hitler’s face spliced together that read: Putler War Criminal.

“I don’t like it,” Valentina Pisilova, a pensioner from Narva watching the Ivangorod show, said of the poster. “It’s low.” On the stage in Ivangorod, there were performances by Russian pop singer Tatiana Bulanova, who rose to fame in the 1980s with the band Letni Sad, and Georgian-Russian singer Soso Pavliashvili.

Narva. Photo: Vladislava Snurnikova, for Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Europe Day organisers seemed to opt for acts appealing to a wider audience. Anne Veski, a 69-year-old pop singer and nublu, one of Estonia’s most popular rappers, took to the stage. Both singers perform mostly in Estonian but also have Russian language songs in their catalogues.

Though both events were well-attended, a significantly larger crowd watched the gathering in Ivangorod, with many locals saying that the history and emotions of Victory Day took precedence.

nublu concert, Europe Day, Narva, 9 May 2025. Photo: Jack Styler

“It’s an easy choice,” said Vadim Smirnov, who watched the Victory Day event from Narva. “The 9th of May,” he said, is “a big and partly religious event because, for us, it’s the day when we saved our country, our nation from extinction. And when I mean nation, I don’t mean one Russian nation, but all nations of the Soviet Union. Most of all, our grandparents were participating in this war,” said Smirnov. “We understand this importance.”

Officials in Ivangorod first erected a stage and screens facing Narva in 2023 after the Estonian government took measures to address Russia’s lingering influence in the country, including switching the language of instruction in all public schools to Estonian and removing all Soviet monuments from the country. In Narva, locals resisted the removal of monuments, resulting in multiple arrests.

The Narva Museum first suspended a banner reading Putin War Criminal with a blood-spattered portrait of the Russian leader in 2023, a little over a year after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Since the first concert in Ivangorod, news of the spectacle has spread throughout the Russian-speaking communities of the Baltics and beyond. “It’s our first time here,” said Tatjana Mahotina, who travelled with her family from Jūrmala, Latvia to celebrate. “It’s very important for us.” Tourists from the United States and China also came to check out the events.

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, officials in Narva have taken a careful approach to regulating celebrations on 9 May. Unlike in neighbouring Latvia, which banned all non-Europe Day celebrations on 9 May, Estonian authorities have not stopped residents of Narva from gathering to watch the Victory Day entertainment. However, the government has banned symbols of Russian aggression, including the black-and-orange Saint George’s ribbon, which has historically been worn on Victory Day and officially been labelled by Putin a “symbol of military glory”.

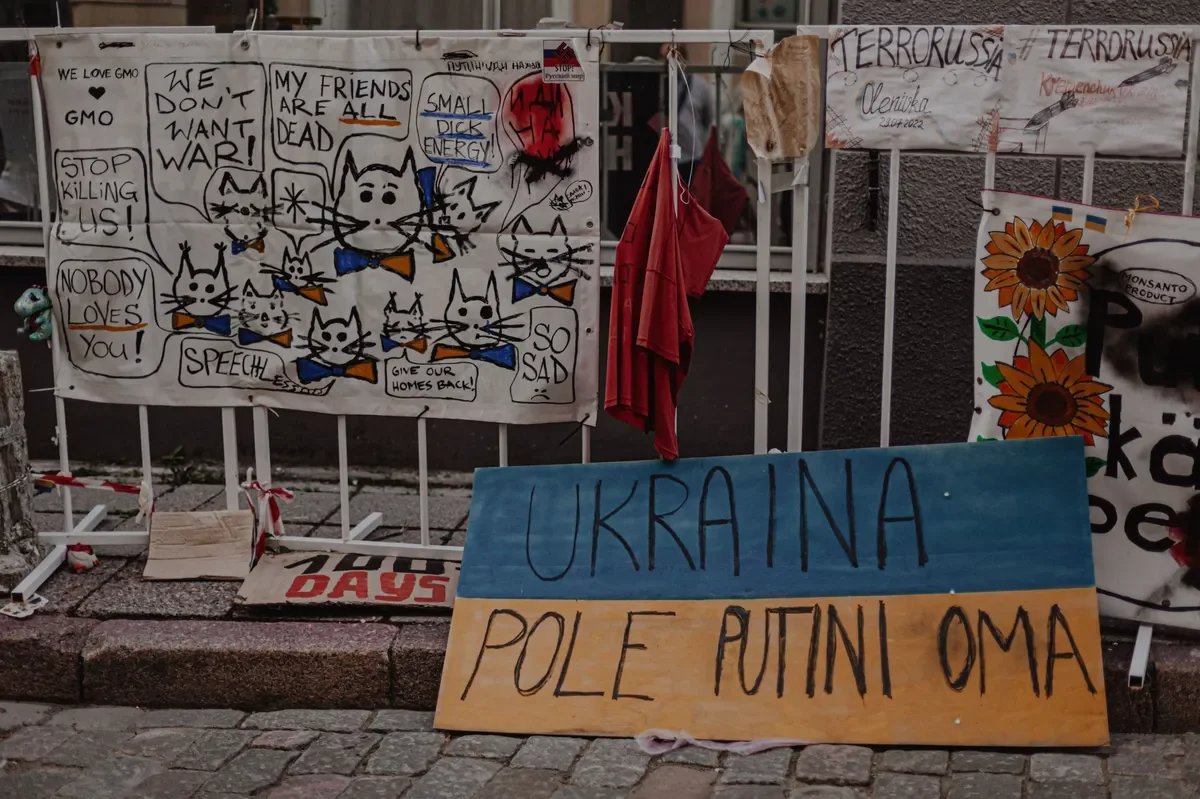

Posters in support of Ukraine in Tallinn. Photo: Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

“After Yeltsin, the one thing that most Russians can agree upon is victory over fascism in the Second World War,” said Andres Kasekamp, a professor of Estonian studies and history at the University of Toronto. As Putin has increasingly tied his government to that victory, “that leaves Estonians and Latvians with the counternarrative,” said Kasekamp. “There doesn’t seem to be any middle ground between liberator and occupier.”

Local museum makes a stand

Housed in the Narva Fortress that directly faces Ivangorod, the Narva Museum has confronted the legacy of the Soviet Union and the current Russian military aggression.

The Narva Museum first suspended a banner reading Putin War Criminal with a blood-spattered portrait of the Russian leader in 2023, a little over a year after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, prompting Russian border guard authorities to request an impromptu meeting with their Estonian counterparts demanding the sign be taken down, but to no avail. The same banner was used during the 9 May celebrations the following year.

In January, Russia issued an arrest warrant in absentia for Narva Museum director Maria Smorzhevskikh-Smirnova for spreading “fake news” about the Russian army. Smorzhevskikh-Smirnova called the ruling a “great honour” in a statement to the Estonian public broadcaster.

Narva is overwhelmingly ethnically Russian because the Soviets did not allow the pre-war residents to return after the Red Army destroyed upwards of 95% of the city in a devastating bombing campaign.

Last year, the Narva Museum once again stirred controversy in the city when it opened an exhibit called Narva 44, which showcased how the Soviet army destroyed Narva during World War II and compared that destruction with photographs of demolished infrastructure in Ukraine.

In late April, an unidentified assailant assaulted Madis Tuuder, a historian who helped put together Narva 44, in Narva’s city centre, reportedly kicking him and breaking his glasses. Tuuder told local media that the attackers accused him of telling “incorrect history” in a series of lectures he had completed about the Soviet destruction of Narva. Narva police department head, Indrek Püvi, confirmed that they were aware of the incident and had identified a suspect. However, the suspect’s “exact motive is still being determined,” Püvi told Novaya Gazeta Europe.

On 9 May, as the sounds from the Russian event echoed throughout Narva, Smorzhevskikh-Smirnova and Tuuder opened a new exhibition, Narva 54, which continues the story of demolition and reconstruction begun in Narva 44.

View of Ivangorod Fortress, in Russia, from Narva, Estonia. Photo: Jack Styler

Today, Narva is overwhelmingly ethnically Russian because the Soviets did not allow the pre-war residents to return after the Red Army destroyed upwards of 95% of the city in a devastating bombing campaign. As a result, most current residents, descendants of the Russian workers brought to Narva after 1945, do not share the Estonian collective memory of World War II.

Tuuder told Novaya Gazeta Europe that he wasn’t sure how the new exhibit would be received by locals. “There are certainly some problems in the east,” he said. “But we have some people among Estonians also who are not very loyal.” The museum also set up a special exhibition memorialising the children of Ukraine who have been killed by the Russian military. The pop-up exhibition will run for only four days, from 8 May to 11 May.

Estonia has given a higher percentage of aid in terms of GDP to Ukraine than any other country, and former Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, who now heads EU foreign policy, has been one of Putin’s most ardent critics.

Improvised memorial where monument in Narva once stood. Photo: Vladislava Snurnikova, for Novaya Gazeta Europe

Regional tension

Relations between Tallinn and Moscow are at a low point. In April, Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service Director Sergey Naryshkin said that the Baltic countries and Poland would be the “first to suffer” if there were a direct conflict between NATO and Russia.

Estonia has given a higher percentage of aid in terms of GDP to Ukraine than any other country, and former Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, who now heads EU foreign policy, has been one of Putin’s most ardent critics. Last year, Moscow put her on a “wanted list” for leading the charge to take down Soviet monuments in Estonia.

All three Baltic states closed their airspace to those heading to Moscow for Victory Day celebrations, namely Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico and Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, the only two European leaders who made the trip. Much of the tension between the two countries has played out in Narva and the surrounding Ida-Viru County, where ethnic Russians make up the majority of the population and Russian is still the language of the majority.

Last May, Russian border guards removed 24 buoys that Estonian authorities had placed in the Narva River, which demarcated the water boundary between the nations. In April, Elisabeth Braw, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Security Initiative, called the incident another instance of creeping “gray-zone” aggression from Moscow in the pages of Foreign Policy.

The Estonian military also announced last month that it would be establishing a new base in Narva, housing 200-250 soldiers on a permanent basis to build up the Estonian military force in the city. Estonian Major General Vahur Karus told Estonian national radio that the military base is “something we owe Narva — the EDF has had very little visible presence there. Narva is the only major Estonian city where that’s been the case”. The base, he continued, would “provide a kind of guarantee to Narva residents that yes, we are here, this is Estonia, and it is very clearly an Estonian city”.

Though the crowds at the Europe Day concert were much smaller than those that watched the Russian Victory Day concert, it may have given a glimpse into the country’s future. Much of the crowd lined up to watch the Victory Day celebration skewed older.

Today, the Friendship Bridge, which connects Narva to Ivangorod, is closed to vehicle traffic, and the Estonian-side is lined with anti-tank dragon’s teeth.

A more complicated reality

After both the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there has been much written about potential security concerns in Narva given its large Russian population. Yet, the position of many ethnic Russians is much more nuanced.

“We make this assumption that none of them want to learn Estonian,” said Janus Paurman, a Tallinn resident who frequently works with the Russian minority in Ida-Viru County. “I see those Russians who want to learn Estonian. I see those Russians who want to learn about Estonian culture.”

Kaja Kallas speaks at a press conference in Athens, Greece, 10 October 2023. Photo: EPA-EFE/YANNIS KOLESIDIS

Kasekamp agreed that speculation of an imminent Russian invasion supported by ethnic Russians in the Baltics was exaggerated. Though there may be ethnic Russians living in northeastern Estonia who may sympathise with the Russian army’s actions in Ukraine, “if you ask them if they want to trade their euros for rubles, or trade Estonian healthcare for Russian healthcare, or Estonian pension for a Russian pension ... the answer will be different,” said Kasekamp.

At 79, life expectancy in Estonia is also about nine years higher than in Russia, according to data from the World Health Organisation and Estonian government statistics.

Demographic shift

Though the crowds at the Europe Day concert were much smaller than those that watched the Russian Victory Day concert, it may have given a glimpse into the country’s future. Much of the crowd lined up to watch the Victory Day celebration skewed older, while teenagers were packed tightly by the stage to watch nublu’s set.

Daria Avdoshina, an organiser at a local youth centre, helped decorate the city in preparation for the Europe Day event. She said that the turnout at last year’s Europe Day had surprised her. “I thought no one would come [because] everyone would be there watching the Russian side. But actually all the young people and all the families came to the Europe Day, and it was such a heartwarming feeling.”

This year, she was looking forward to seeing nublu’s set. “Here in Narva people usually do not listen to Estonian music but as he [has] a song about Narva, I think everyone’s waiting for that.” The song in question, For Oksana, tells the story of nublu pining for a Russian girl in Narva with a Saint George’s ribbon “entwined forever” in her hair. His set, which featured pyrotechnics and smoke machines, saved For Oksana until the end. As he reached the chorus, shouting out “it’s life, it’s karma/hey Narva city”, the crowd duly went wild.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]