In order to circumvent strict international sanctions imposed on it following the invasion of Ukraine three years ago, Moscow has assembled a vast “shadow fleet” of ageing oil tankers sailing under the flag of poorly regulated third countries to allow it to continue exporting oil to earn the petrodollars vital for its prosecution of the war.

However, four mysterious explosions on shadow fleet oil tankers in the Baltic and Mediterranean Seas in the past three months have made many wonder whether, as well as undermining the sanctions on Russia, the fleet poses a growing threat to the global ecosystems.

On average, three shadow fleet tankers left Russian ports per day last year, transporting some 84% of all Russian oil exports. Who maintains the fleet, which is estimated to number anywhere between 300 and over 1,000 tankers, and who inspects them for seaworthiness is not known.

The risks inherent in operating this aged fleet are further exacerbated by their often unreliable insurers, and the fact that the tankers often disable their maritime tracking systems to avoid being monitored, which massively increases the chance of colliding with another vessel on the open seas.

In the event of an accident, cleaning up an oil spill can cost anywhere between €1.4 billion to €2.7 billion, depending on the region, says Petras Katinas, an energy analyst at CREA.

While the Volgoneft 212 tanker, which broke in half in December in the Kerch Strait between Crimea and Russia and caused an environmental disaster on the Black Sea coast, is not a shadow-fleet tanker, it was carrying fuel for a ship named FIRN, registered in Panama, which is part of the Russian shadow fleet, according to the Ukraine War Environmental Consequences Work Group, which employs both Russian and Ukrainian environmentalists.

At least four dangerous incidents involving vessels in the Russian shadow fleet have taken place over the past year. The tanker Seacharm was damaged by an explosion in the Turkish port of Ceyhan, and the same fate befell the Grace Ferrum in Libyan waters. Two similar incidents occurred in February, one on board the tanker the Koala in the port of Ust-Luga on Russia’s Baltic coast, the other on the crude oil tanker the Seajewel, at the Italian port of Savona. The cause of these explosions remains unknown, but Reuters cited vessel tracking data and sources to confirm that Seacharm, Grace Ferrum and Seajewel had all recently called at Russian ports.

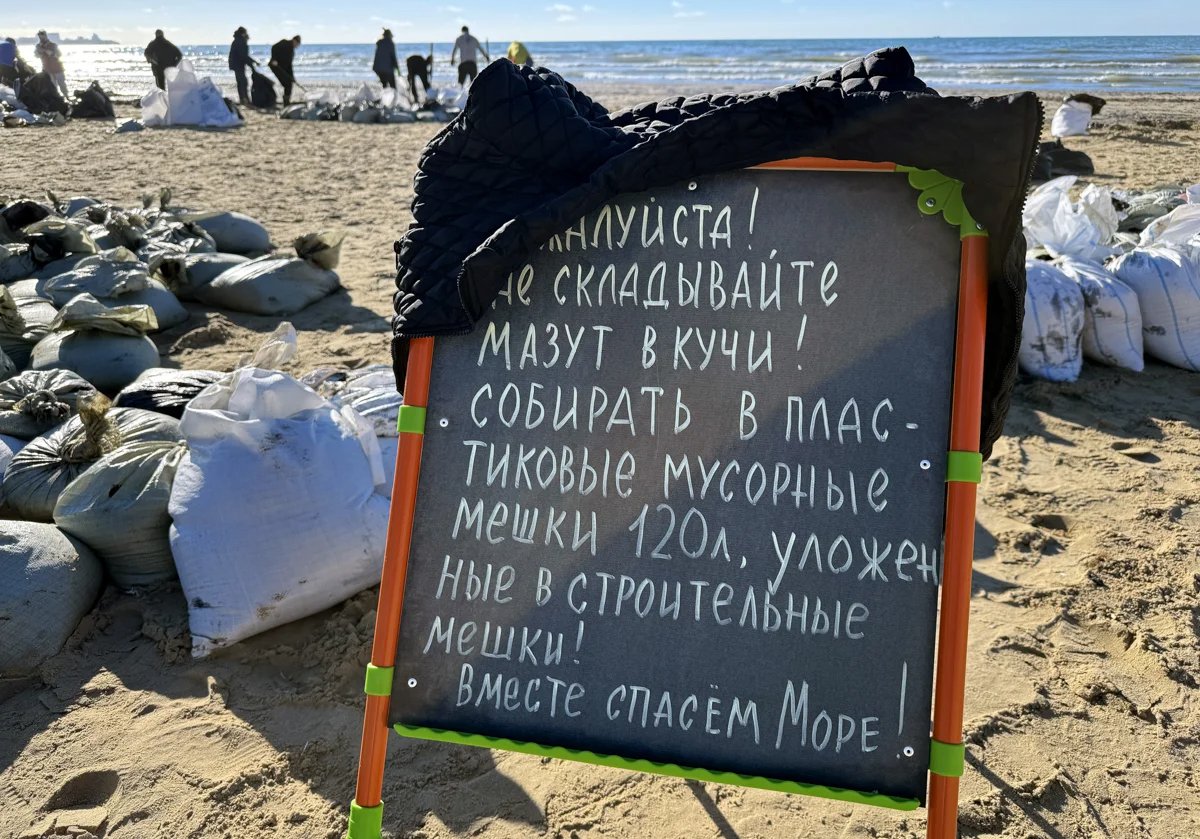

A sign instructs volunteers how to treat oil washed up onto the beach in the aftermath of the Volgoneft oil spill. Photo: IMAGO / SNA / Vitaly Timkiv / Scanpix

In addition, several technical failures that were logged could have led to major oil spills, according to the independent Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). In December, the Eventin tanker drifted off the coast of Germany with almost 100,000 tons of oil on board after its crew lost control of the ship, prompting Germany to impound the vessel. In May, the engine of the Sea Marine 1 oil tanker failed in the Dardanelles as it sailed from Greece to Russia.

The Russian shadow fleet was involved in over 30 incidents around the world between 2022 and 2024, according to Isaac Levy from CREA. However, compiling a full list of incidents is extremely difficult, Levy says, due to both the secrecy surrounding the tankers and the refusal of their operators to share data. Such vessels often fly the flags of convenience of Panama, the Comoros and Liberia, countries whose enforcement of the law is known to be relatively lax, Levy adds. To limit any individual operator’s possible losses, each tanker is usually registered with a separate company.

Causes for concern

The age of the vessels in Russia’s shadow fleet adds to the environmental risks it poses, Levy says. Whereas the global average age of an oil tanker is 13 years, according to S&P Global, the average Russian shadow fleet ship was 18 years old in late 2024, and a third of them were over 20 years old, according to international consultancy Oxford Analytica. CREA says many ships used by Russia to circumvent sanctions have been in service for over 30 years.

But the lack of regular inspections and poor maintenance are more of a danger than their age, says Levy. “Shadow fleet vessels avoid inspections and are haphazard in their observation of safety precautions,” Russian independent energy expert Tatyana Lanshina agrees.

Russia-affiliated tankers on the sanctions list cannot be serviced and repaired at EU or G7 country shipyards, says Sergey Vakulenko, a senior researcher at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin. “They probably wouldn’t be accepted at shipyards in Singapore and South Korea, or at respectable ports in friendly countries. So it’s highly likely that they will use the services of second- or third-rate repairmen,” Vakulenko told Novaya Europe.

The same international restrictions make it difficult for the ships to use maritime pilot services, only further increasing risks. Shadow fleet tankers also transfer oil from one ship to another on the open sea, which is illegal. The practice often occurs at night and in rough conditions, both factors increasing the risk of an oil spill.

A dead dolphin washes up on the beach following the Volgoneft oil spill. Photo: IMAGO / SNA / Vitaly Timkiv / Scanpix

The fleet’s inherent secrecy presents a further risk, Lanshina says, adding that shadow fleet ships often lie about their location. The practice, known as spoofing, has become commonplace for tankers exporting oil from Russian ports in the Baltic, according to the Finnish Coast Guard. They disable the automatic identification system (AIS), making it difficult to find them in case of an accident, if they emit a signal at all. A tanker shutting down its AIS can also cause accidents as other ships might only notice them when it’s too late to avoid a collision, Levy says.

In the event of an accident, cleaning up an oil spill can cost anywhere between €1.4 billion to €2.7 billion, depending on the region, says Petras Katinas, an energy analyst at CREA.

The routes of the shadow fleet reflect the routes of Russian oil exports: at least 40% of ships pass through the Baltic Sea and the Danish Straits, then through the Mediterranean Sea and the Suez Canal, according to Bloomberg data as of January.

About the same number go from Pacific ports to Asian countries. The remaining 10-20% set off from the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiysk to the Mediterranean Sea via the Bosphorus Strait and the Dardanelles.

Individual tankers take the Northern Sea Route (NSR) via the Arctic to export raw materials from Lukoil and Gazpromneft’s Arctic oil fields and to transport crude oil from Russia’s Baltic ports to China to bypass the Suez Canal. Shadow fleet ships in the Arctic Ocean pose a particular risk, according to Lanshina. “It would be particularly difficult, if not impossible, to clean up an oil spill and to save the crew” in frozen conditions, she says.

Overblown fears?

For all the reasons described, it may feel obvious to conclude that Russia’s shadow fleet is more accident prone than better maintained and regulated oil tankers operating within the law.

As Vakulenko is keen to point out, the largest oil spills of recent decades were both caused by oil tankers far younger than the average age of the shadow fleet, one of which was 10 years old and the other 14.

In media coverage of the oil tankers carrying Russian oil ran into difficulties off the coast of Sweden and Germany, depicted the situation as one in which only a miracle prevented the tankers from running aground and causing an oil spill, Vakulenko recalls.

But statistics from monitoring website EMSA show that while ships going to or from Russia get into between one and three such incidents a year, the remaining tankers in EU waters combined are involved in between 15 to 25 such incidents annually, Vakulenko says, adding that the number of accidents has not increased since 2022, and none of the more than 250 accidents recorded since records began in 2011 has led to an oil spill.

While Vakulenko concedes that those statistics do not guarantee that shadow fleet tankers won’t be responsible for dangerous incidents in the future, he stresses, however, that “these worries also apply to regular vessels and the statistics on accidents do not yet bear out the theory that the shadow fleet is significantly different in this regard.”