Since St. Petersburg’s Erarta Museum of Contemporary Art first opened its doors in 2010, its exhibitions have pushed the limits of creative and political conformity, a challenging task that has only become more so as Russia sinks ever deeper into authoritarianism.

Housed in a renovated neoclassical Stalinist building that was once home to the district Communist Party and then St. Petersburg’s Synthetic Rubber Research Institute, the impressive five-storey space teems with works by primarily young, almost exclusively Russian creatives, and it’s easy to see why Erarta was central to the public fascination with contemporary art that gripped Russia during the relatively liberal 2010s.

Today though, while Russia’s largest museum of contemporary art still enjoys far greater creative freedom than the country’s publicly-funded museums, it’s arguably tempered by the greater scrutiny it has received from the authorities since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Since then, cultural institutions have faced growing political pressure, as evidenced by the Gulag History Museum’s 2024 closure following its refusal to alter a display to align with Kremlin narratives. So in January, when several pro-regime voices publicly began criticising works on display in the museum, it seemed that Erarta might be at risk of being shut down too.

The art of war

Erarta’s present difficulties began in January, when Sergey Mironov, a member of Russia’s State Duma and leader of the party For a Just Russia — For Truth, called for an investigation into what he described as the museum’s “anti-patriotic exhibits” and calling it “unacceptable” that such artworks be on display in Putin’s hometown, of all places.

As he spoke, his aides brandished photos of pieces he found particularly objectionable, such as Yevgeny Kondratyev’s interactive Welcome to Russia, a life-size matryoshka doll that swings open to reveal internal spikes akin to those of an iron maiden, or Yuly Rybakov’s sculpture Big Brother, in which an egg nestled in a crown of barbed wire is targeted at close range by a revolver.

Photo: Yevgeny Kondratyev’s Welcome to Russia at the Erarta Museum. Photo: @pavluchenkovaav / Telegram

The transgressive content of the museum appears to have been brought to Mironov’s attention by Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova, who heads his party’s youth wing. It was Pavlyuchenkova’s visit to Erarta earlier in January that led her to post examples on Telegram of the “dozens of works” in the museum that she alleged promoted Russophobia and “devalued” traditional Russian symbols.

Highlighting the links between Erarta and other organisations that she considered to be undermining the state, such as the Yeltsin Center, Moscow’s Gulag History Museum and the Soros Foundation, Pavlyuchenkova nevertheless stressed that the party was not calling for its closure but simply wanted the governor of St. Petersburg to step in to “restore order” to the institution.

Then, as deputies from the New People Party came out against A Just Russia in support of the museum, an active, if relatively tranquil debate in the State Duma ensued, with Deputy Ksenia Goryacheva of the New People party warning that closing the museum would be a “tragic page” in the city’s history books; while St. Petersburg Legislative Assembly member Dmitry Pavlov resolved to go along in person to acquaint himself with the exhibits, even getting into the matryoshka doll, and urging everyone to follow his lead, explaining that “art lives through dialogue, diversity of opinions and emotions.”

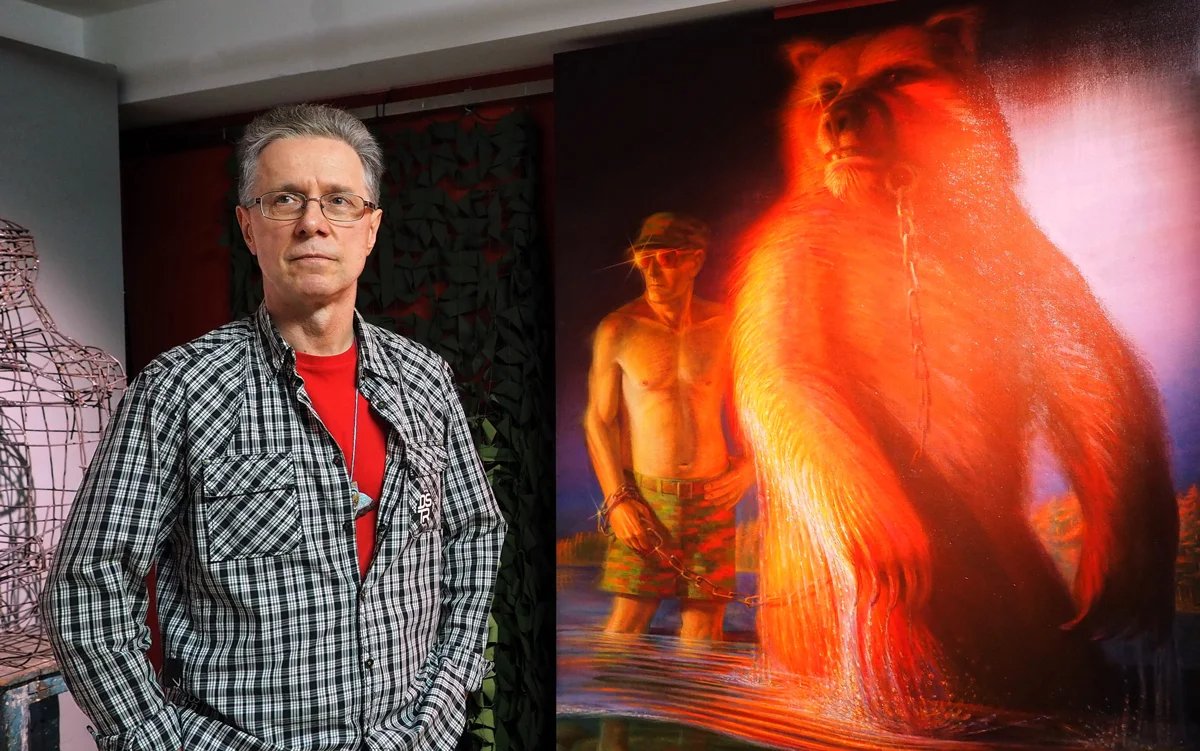

Photo: Vadim Grigoryev-Bashun in front of his painting Bathing of the Red Bear at the Erarta Museum, 1 April 2023. Photo: Alexander Chizhenok / Kommersant / Sipa USA / Vida Press

Before long, St. Petersburg’s vice governor for culture and sport, Boris Piotrovsky, entered the fray to deliver an official response. Speaking to a local TV channel, Piotrovsky admitted that he had not seen the scandalous matryoshka itself, but said that, having been to Erarta many times, he understood the “bewilderment about some of the exhibits”. While reaffirming the importance of freedom of expression, he nevertheless listed a number of other federal, regional and private museums that people could visit instead where, he said, the exhibits didn’t usually “provoke such concerns”.

Formerly friendly

There was a time, not too long ago, when Erarta was considered a Kremlin-friendly establishment. Indeed, when in 2021, Znanie, a Kremlin-backed educational propaganda non-profit which has since been sanctioned by the EU, helped organise a three-day event at the institution, none of the high-ranking cultural officials in attendance felt compelled to complain about any of the museum’s exhibitions.

Within Russia’s artistic community, the museum has a reputation for housing brash works in kitschy frames and is often criticised for its eclectic, omnivorous approach to curation

But that was then, and changes to Russia’s post-war political climate have seen much in the public sphere come under greater scrutiny, Erarta being no exception. In 2023, when Vadim Grigoryev-Bashun’s painting Bathing of the Red Bear was presented at the annual Erarta Prize show, one disgruntled visitor was moved to lodge an official complaint, arguing that the 2020 work, which depicts a bear being led on a chain by a man resembling Putin, discredited Russia, its president and the so-called “special military operation”.

Though no case was ever brought against the museum for displaying the piece, Grigoryev-Bashun has since had many of his shows elsewhere in Russia cancelled or postponed.

Sergey Grynevich’s painting Festival, which features the slogan “Long live Belarus”, on display at the Erarta Museum, 15 April 2021. Photo: Alexander Chizhenok / Kommersant / Sipa USA / Vida Press

In July, Erarta did finally find itself subjected to legal proceedings when it was charged for displaying Sergey Grynevich’s painting Festival in 2020, which prosecutors argued contained “Nazi symbols” due to its inclusion of the phrase “long live Belarus”, an innocuous sounding slogan that was banned in Belarus due to its association with the anti-government protests that took place the same year. However, the case was ultimately dismissed due to the expiration of the relevant statute of limitations.

Siege mentality

Erarta has long been an outlier in the Russian art world, having alienated many with its modus operandi, well before sycophantic officials and moral crusaders began to target the institution. The museum’s inscrutable curational choices often appear to follow an internal logic, its exhibitions are developed using closely-guarded in-house creative criteria, it lacks clear museum design, and visitors are not presented with any typical forms of art mediation. Perhaps most confounding of all, a single entry ticket costs more than an annual pass, but requires filling out a questionnaire and taking a photo as Erarta uses facial recognition for entry authorisation.

Within Russia’s artistic community, the museum has a reputation for housing brash works in kitschy frames and is often criticised for its eclectic, omnivorous approach to curation that has left its space crowded with works from an enormous number of schools and in a huge array of styles.

Erarta is the brainchild of Marina Varvarina, the widow of multimillionaire businessman Dmitry Varvarin, who was killed 25 years ago in what was believed to be a targeted assassination. The case went unsolved and within a few years of his murder, Varvarina had sold her inherited assets. Since then, she has cut a low profile, reportedly splitting her time between London, the Channel Islands, and her native St. Petersburg. Her exact net worth is unknown, and when pundits reported that it had cost some $30 million to open Erarta in 2010, the museum neither confirmed nor denied the figure.

Varvarina, who is as private as her brainchild museum is enigmatic, has always appeared unconcerned with professional criticism and did not speak publicly about her creation until 2019, when, giving an interview to promote a children’s book she had written, she said that Erarta had never been intended to “impress a narrow group of specialists.”

Unlike many of St. Petersburg’s more traditional museums, Erarta’s focus is unashamedly on the visitor experience, and the fact that many well-known St. Petersburg artists continue to show their work there, drawn by the museum’s huge audience, clear humanist values and substantial budget, is arguably proof of Varvarina’s philosophy, that “a wholehearted approach is not amateurish.”

The opening of the 2025 Erarta Prize exhibition at the Erarta Museum, 6 February 2025. Photo: Alexei Smagin / Kommersant / Sipa USA / Vida Press

At this year’s annual Erarta Prize competition-exhibition, the museum’s democratic ethos became a criterion for evaluation, with each work’s description including its digital footprint, how many likes and comments the piece garnered on social media, while being unburdened by philosophical or cultural references. In keeping with that spirit the prize will be awarded based on an audience vote.

While critics might label Erarta as populist in its approach, perhaps the lesson to be taught by the museum is that contemporary art should be inherently democratic — not many collections in contemporary Russia currently allow for reflection on difficult social questions, and their function is, after all, to speak to visitors in language they understand.

Another potentially valuable lesson to be drawn from this situation is that the ever-more vulnerable private art community can no longer afford to alienate the public by being elitist or fragmented if it is to survive in contemporary Russia. Erarta may have survived the scrutiny of the public spotlight this time, but it may not be so lucky in the future.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]