This article was originally published by Novaya Gazeta Baltic

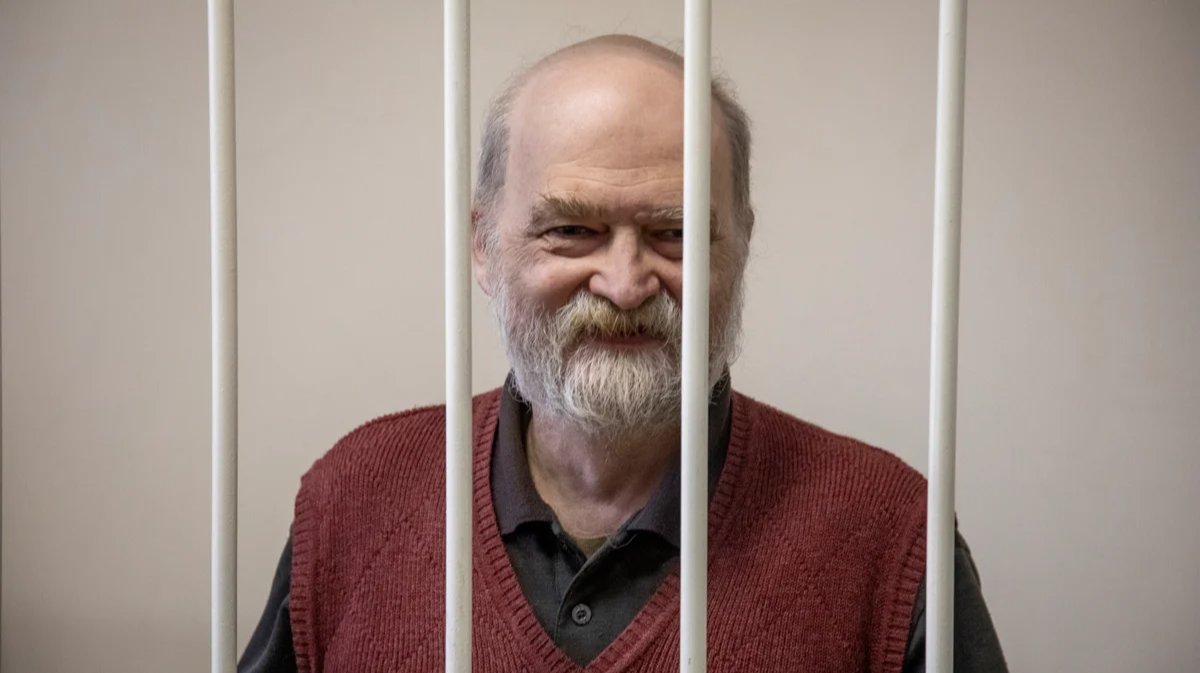

In early April, 66-year-old dissident Alexander Skobov was arrested for allegedly “justifying terrorism” in his posts online. For his friends and family members, the arrest came as no surprise.

Skobov, a long-time dissident who was made to spend seven years in a psychiatric ward after taking part in protests against the Soviet authorities in the 1970s, had published multiple posts condemning Russia’s actions in Ukraine since 2014. In March he was named a “foreign agent”, and since then people close to him said his arrest had seemed inevitable.

“He and I talked a hundred times about the fact that he would be arrested — if not today then tomorrow,” said Skobov’s friend Yuly Rybakov, a human rights activist and former deputy in the State Duma, Russia’s lower house of parliament. “People have been imprisoned for much less.”

Skobov’s 90-year-old mother, whom he lives with and cares for, said she had been having nightmares about his arrest for months before it happened, and Rybakov recalled that Skobov himself said he “didn’t understand” why the authorities hadn’t come for him yet.

Skobov’s mother Natalia. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov

Skobov’s children, who moved abroad long before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, urged their father to flee the country when they saw him in Istanbul in early March. Other friends have also tried to convince him to leave and avoid arrest, citing his many health issues, including severe diabetes, hepatitis C, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and near blindness.

But, Rybakov said, Skobov was resolute, telling him that he “wanted to be part of his own judicial process” when he was inevitably arrested.

Rybakov said that Skobov had been “driven to despair” by what had been happening in Russia in recent years and “felt that someone had to be radical”.

Another friend, Mikhail Sedunov, said that trying to convince Skobov to change his course of action was like “grabbing the wing of a plane that was already accelerating down the runway”.

On 2 April, masked policemen arrived at Rybakov’s flat, where Skobov had been staying. When Rybakov left to take the dog for a walk, the police reportedly entered the property, threw Skobov to the ground, twisted his arms and handcuffed him. According to Rybakov, Skobov “defiantly” refused to take either warm clothing, his diabetes medication, or his glasses with him, intending these gestures as an “act of protest”.

Skobov’s wife, Olga Shcheglova, managed to buy him replacement medication and glasses, which she brought to him ahead of his interrogation by Russia’s Investigative Committee. But Skobov refused to accept them — a reaction Shcheglova said she had “expected” from her husband.

Olga Shcheglova bringing a package to Skobov in a pretrial detention centre. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov

Resistance to the authorities and a fight for justice had defined Skobov’s life for more than four decades. His first foray into political activism was in 1976, when he and other university students in St. Petersburg scattered leaflets calling for the “establishment of true humane socialism” and the “overthrow of the tyranny of officials” ahead of a meeting of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The students were expelled from university and brought before a court, and some, like Skobov, were then sentenced to compulsory treatment in psychiatric hospitals because, according to Rybakov, it was believed that “only crazy people could dislike the Soviet regime”.

Skobov’s radical spirit remained unquelled when he was finally released from hospital in 1981, however, and he immediately joined the Free Interprofessional Association of Workers, a dissident group that led the first attempt to create an independent trade union in the USSR. In 1982 he was arrested for his involvement with the group and sent back to hospital, where he spent another three years.

Photos of Skobov from his personal archive. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov

In the early 1990s Skobov taught history at a secondary school for gifted students, writing and publishing his own award-winning textbooks. But later in the decade political activism again became the focal point of his life as he took part in protests against the Chechen wars.

When Russia annexed Ukraine in 2014, Skobov took to social media to rail against the regime, openly supporting Ukraine and condemning Russia’s military action. The same year, two unidentified men armed with knives attacked him outside his home in what his friends and family members say they are sure was retribution for his criticism of the regime.

Even this did not deter him, however, and his friends said his statements opposing Putin’s rule became “even sharper, more unrestrained, and more radical”. Speaking last year at the Free Russia Forum, an opposition conference held biannually in the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, Skobov condemned the regime more harshly than any of the other attendees, despite being one of the only participants still living in Russia.

Another friend of Skobov, Nikita Yeliseyev, said he doubted Skobov would survive the 7.5-year sentence that he is almost certain to receive.

“He is an old man,” Yeliseyev said. “And he has a number of very serious illnesses.”

Sedunov said all of Skobov’s actions stemmed from a desire to “struggle, as vigorously as possible, against the obvious evil represented by the current Russian government”.

“This is the way he was brought up: he wanted to fight evil any way he could. And this was the only way left,” Sedunov said.