Russians currently spend almost twice as much money on esoteric “services” as they do on medicine, with it now being established practice for fortune-tellers and psychics to claim they can prevent people being drafted into the army, or even divulge when the war will end. Could Russian propaganda be a factor in the country’s growing fascination with the occult?

This article was originally published in Novaya Gazeta Baltic.

Two days after Russia announced the partial mobilisation of its military reserve in September 2022, an eccentrically-worded post by Crimean rune expert Yury Kontomirov appeared on Russian social media network VK.

“We have a formula that will protect you from being called up to go to war,” Kontomirov wrote. “And if your husband or son has already gone to war, it will keep them alive.” He explained that the formula couldn’t be given away for free but that the money paid for it would “help your sons and husbands come home alive — or protect them from being called up if they haven’t been already. You need to have the formula with you at all times (!) until the war is over.”

As Kontomirov’s post might suggest, the war in Ukraine has led to a growing demand for esoteric services.

There is no accurate data on what proportion of Russians regularly turn to fortune-tellers and psychics, but some estimate the market to be worth about 2 trillion rubles (€20 billion) annually.

For comparison, the national statistics agency Rosstat says Russians spent barely half that amount on medicine in the first 10 months of 2023. Tarot card sales are also on the rise, according to online retailer Wildberries, which went from selling just 83 decks in 2020, to some 16,000 in 2023.

Anthropologist Olga Khristoforova cautions against rushing to too many conclusions, though, noting that a boom in esoteric services has been seen in the West as well as in Russia and can be traced back to the Covid-19 pandemic, during which sales of books on the occult increased by more than 50% in Russia.

Uncertainty about the future created a market for some form of spiritual reassurance, and people also had a lot more free time during lockdown, which was used by many to take up a range of esoteric activities and to seek new sources of income by taking courses in tarot reading, for example.

Dear God, it's me, Vladimir. Photo: Alexander Zemlianichenko / EPA-EFE

Neo-medievalism

The growth of esoterica in the 2020s is the ideological inheritance of the 1990s, when neo-medievalist practices began to appear in Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union. In the Russia of the 1990s, Khristoforova says, people stopped seeing science as beyond reproach. Some began to reject facts altogether, while others sought alternatives in the guise of mystical and esoteric practices.

Interest in the esoteric decreased slightly during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s first two terms in office due to his regime’s support for the Russian Orthodox Church, but it didn’t die out entirely, Khristoforova says, pointing to the popularity of Russian TV programmes such as Battle of the Psychics. With increased internet access, esoterica found a wider audience in Russia, which was further boosted by anxiety over the pandemic and then over the war.

It is fairly standard for people to seek help from mystics in times of war, Khristoforova says, noting that Soviet women would go to fortune-tellers during World War II to “find out” what was happening to their husbands, brothers and sons, especially when letters stopped coming from the front.

The same thing appears to be happening again now. Indeed, lawyer Ilya Rusyaev estimates that fortune-tellers using methods such as tarot cards and palm-reading to answer questions for clients account for 60–70% of the occult market in Russia today.

Coping strategies

When people experience anxiety, despair and fear due to external circumstances, they seek support in the way most familiar to them, says psychologist and psychotherapist Maria Mitina. Depending on the individual, that may be through psychotherapy, religion or esoterica. It’s clear that the war is affecting Russians’ mental health — spending on antidepressants increased by 70% in 2022 — and fortune-tellers and horoscopes may offer a different way of coping with the same concerns.

A fortune-teller or psychic can help in the short term and relieve anxiety, Mitina says, but the long-term consequences are more likely to be harmful. Putting off psychotherapy or medication to help with anxiety and depression will only complicate and lengthen the recovery process.

Tarot-reader and YouTuber Dementy Apollonov told independent media outlet 7x7 in 2023 that over the last two years about 15–20% of his customers had asked about the end of the war and further mobilisation.

Yulia, a specialist in runes, amulets and candles, told Novaya Gazeta Baltic that magic had always existed, but the market for it had actively grown in recent years as people realised the potential it offered for earning money.

Online vendors selling candles and charms against mobilisation are exploiting people’s fear for their loved ones, she says. “My clients have sent me screenshots of their conversations with “experts” who very skilfully wheedle money out of them by playing on their fears. People are too lazy to work things through for themselves. They think that if they pay someone, they’ll have a magic wand, a solution to all their problems. That’s not how real magic works.”

The Russian media regularly reports on swindler mystics. Fraudsters tend to gain people’s trust through con tricks, and then they gradually start offering services for money. Successful fortune-tellers can achieve great financial success. Seven women from Moscow paid “clairvoyants” from the Krasnodar region of southern Russia 24 million rubles (€240,000) over the course of several years for their services. Another Muscovite woman paid a “psychic” from the southern Russian city of Volgograd 67 million rubles (€678,000) to keep her out of harm’s way.

Yulia says that real specialists in magic believe everyone has karmic circles they have to go through. You cannot buy your way out of your debt to karma. She suggests some people killed innocent people in previous wars and are now paying for their old sins. “We can’t cleanse our karma in any way. A person has to work everything off by themselves. So it’s wrong to try to help people avoid the draft. We can only provide mental fortification, not physical protection.”

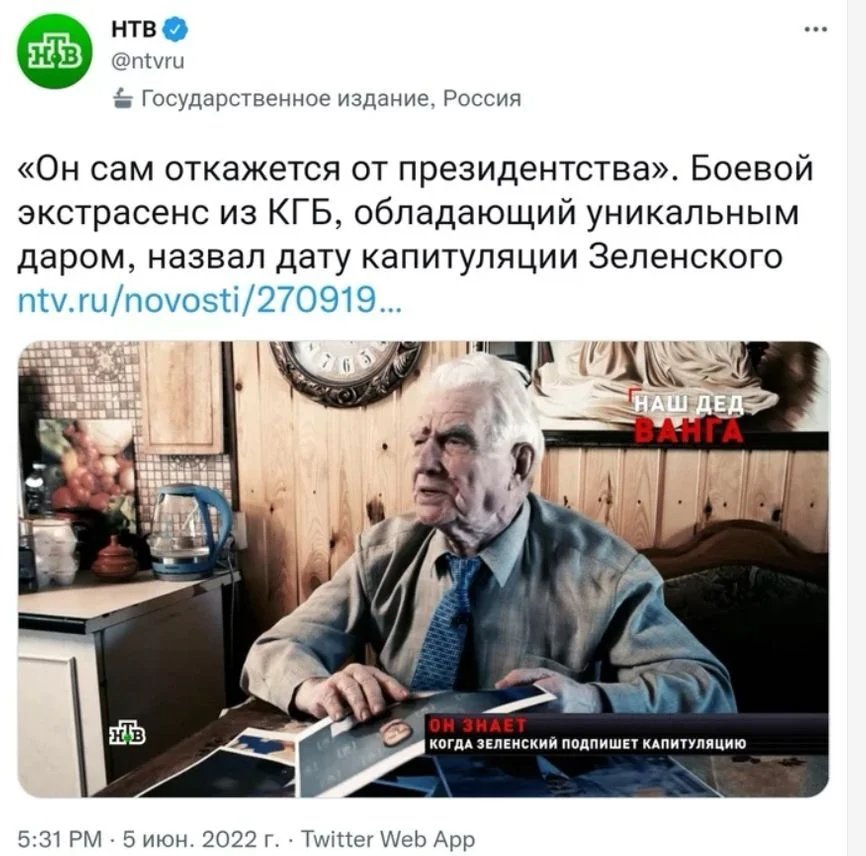

KGB military psychic on NTV social media

Demon-haunted propaganda

Russian propaganda also helps contribute to this neo-medievalism. In 2022, political talk show ratings plummeted, and so TV channels began to vary the guests they invited on. Psychics, fortune-tellers and astrologers gradually replaced political scientists, military experts and propagandists. The psychics invited onto propaganda channels spoke, unsurprisingly, of Russia’s imminent victory while slinging mud at Ukraine and praising Vladimir Putin. In Khristoforova’s words, “esoterica on TV strengthens and stimulates people’s faith in the mystical.”

An interest in the occult is typical in authoritarian and totalitarian regimes waging war, Khristoforova says, adding that esoterica can even help strengthen people’s sense of identity. However, in the post-war environment, it manifests in a different way, and the obsession with the occult becomes more mundane, as people try to find support in the spiritual. In her 2020 book A Demon-Haunted Land, which describes the hold post-war mysticism had on 1950s Germany, US historian Monica Black explains how once the Third Reich had been defeated, it became routine for Germans to turn to fortune-tellers and psychics.

Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov

Literary critic Galina Yuzefovich sees parallels with 1990s Russia. “The reasons behind the upsurge in all sorts of charlatans and obscurantists were similar in Russia and post-war Germany. There had long been a ban on such practices, the public sphere was freer, the ideological system had collapsed and that led to confusion. But the main thing was the accumulated trauma and collective guilt, and an almost complete absence of legal ways to cope and deal with them.”

Khristoforova says she doubts there will be a similar explosion of esoterica when the war in Ukraine comes to an end, mainly as, unlike in the 1990s, these services were already available in Russia. Phenomena such as these only arise in such a striking fashion in the wake of profound economic crisis or regime change, which in turn cause people to search for new forms of authority, she adds.

“For those who watch the current propaganda, they have Putin as a father figure, a god. When he’s gone, they’ll need something or someone else to replace him, and they’ll look for that wherever they can find it, so the emergence of new sects and occult movements is all too possible.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]