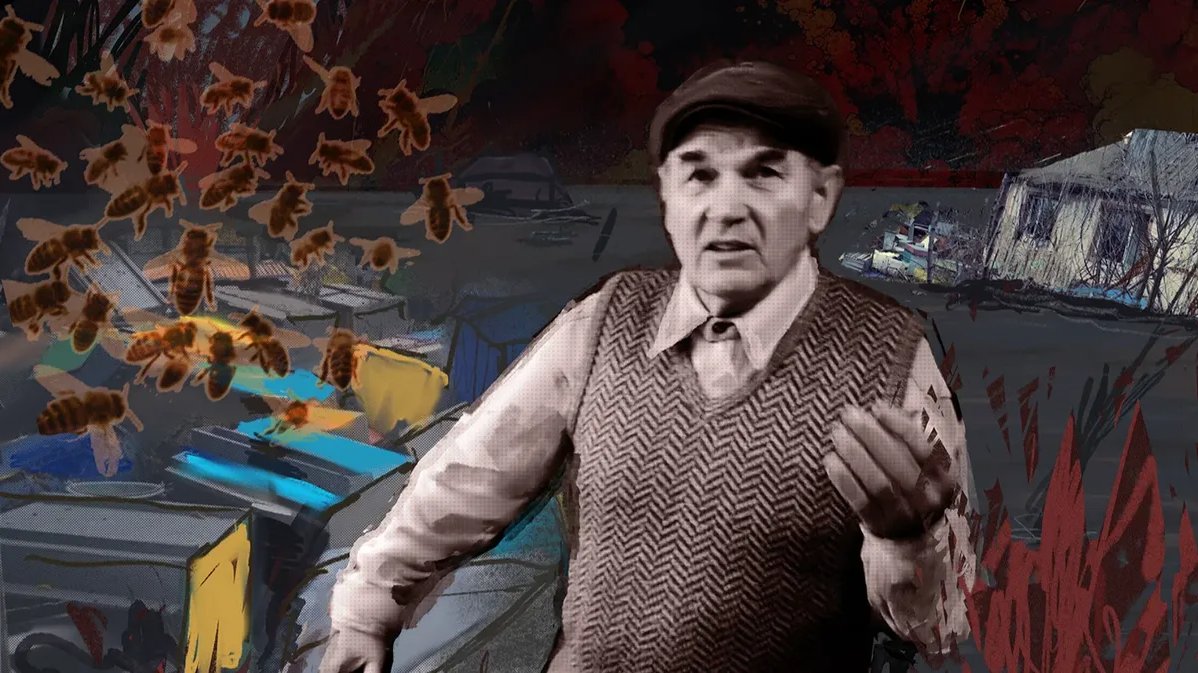

Oleshky native Mykola Stepanskyi, 74, was a professional beekeeper with his own honey farm until the so-called “Russian world” burst into his life and destroyed everything he lived for. His son was taken prisoner and tortured, then his daughter was killed in shelling. Finally, all his bees drowned when Oleshky was flooded by the collapse of the Kakhovka dam in June.

Stepanskyi, his wife Lyda and their two children, Oksana and Oleh, once lived in Oleshky, a town on the left bank of the Dnipro River, in the part of Ukraine’s Kherson region that is now under Russian control.

The family witnessed firsthand the outbreak of war on 24 February 2022 when they heard gunfire and explosions as fighting raged over the Antonivskyi Bridge in the nearby regional capital of Kherson.

Stepanskyi’s grandson Slava, a paramedic in the local ambulance service, received a call that morning reporting dozens of injured people on the bridge: Russians and Ukrainians, soldiers and civilians. The paramedics had no idea who the injured were, Slava says, recalling seeing only severed limbs and numerous corpses.

That night he returned home pale as a sheet. Barely speaking a word for the next two weeks, he was unable to eat, losing 13 kilograms. However, by early March he had recovered to some extent and was able to return to work.

Months later his family would learn that Slava had been forced to take Russian officers by ambulance to Henichesk, a Ukrainian port on the Sea of Azov seized by Russian forces on 24 February, and Armiansk, a town in the north of the annexed Crimean peninsula. The soldiers also forced him to sign a non-disclosure agreement and took his fingerprints. There was no way he could refuse.

Russian troops advancing towards Ukrainian-held territory near Armiansk, Crimea, 25 February 2022. Photo: Stringer / EPA-EFE

Oleh disappears

Stepanskyi’s son, Oleh, then 41, disappeared in the summer of 2022. One Sunday, Oleh called his parents to let them know he was cycling to visit them that day and simply never showed up.

At the time, Russian police officers and soldiers were frequently abducting people from their homes or from the streets in the occupied Ukrainian territories. It turned out that Oleh had been abducted by Federal Security Service (FSB) officers. His worried parents went to the local police station. The police told them they couldn’t do anything, as they had nothing to do with people detained by the FSB, but they did allow them to leave a parcel for him.

For days, the police took parcels of food and clothes, but wouldn’t let the family see Oleh.

“There were stories of people getting their children back from the Russians for a certain sum,” says Stepanskyi. “We were prepared to buy back our son as long as he was still alive, but nobody even mentioned money.”

In the end, Oleh was lucky — he was released after 10 days, though he said the parcels his parents handed over had never reached him. He told his parents that FSB officers had stopped him on the street to inspect his telephone, and detained him “just in case” after seeing messages to a friend he’d written in Ukrainian.

Oleh said that prisoners were given one biscuit each a day and a small bottle of water to share. He wasn’t sure how many prisoners were in the cell, but for a few days there were so many that it was impossible to sit or lie down — you could only stand. He barely slept, and every night the prisoners could hear the terrifying cries of people being tortured.

One woman and her 12-year-old son particularly stuck in Oleh’s memory. They had been put in a cell either because she was the wife of a Ukrainian soldier or because her husband had passed on information to the Ukrainian army — nobody knew for sure.

But every night she was tortured, and every day an elderly man came to the police station begging for the child to be released. Oleh has no idea what happened to them.

All this time, Oleh was left in peace. But on the tenth day, he was taken from the cell to a torture chamber. His arms and legs were spread, and he was beaten and kicked, which caused injuries to his ribs and kidneys. He was given electric shocks in an attempt to make him confess to being a terrorist. But he didn’t buckle.

During the torture, his interrogators kept asking him about his wife and child, who left Oleshky for Ternopil in western Ukraine as soon as the war broke out. His wife’s parents were Ukrainian speakers and feared persecution from the Russians. Oleh’s wife and daughter went with them. Oleh replied that in western Ukraine “Russian speakers are disliked” and the investigator let him go.

Mykola says that anyone released from prison still remained under observation. “The men who were in the same cell as Oleh told him ‘Oleh, hide, otherwise they’ll bring you back. They don’t let anyone out of their clutches just like that.’” After his release, Oleh hid out at his family’s dacha, or with friends.

Mykola says many of their friends in Oleshky have been abducted. A man who lived across the road was knocked to the ground by men in civilian clothing, who then put a black bag over his head, shoved him into a car and drove off. The men tortured him, and tried to make him confess to being a terrorist, but in the end they let him go.

Not everyone has been so lucky. Many corpses have been found in the area. A husband and wife who had a grocery shop were shot in the nearby forest. Another man who had a retail business was found murdered in a swamp. The Russian invaders soon had people earning good incomes in their sights and robbed and killed them from the very beginning of the war.

Oleh decided to flee in September 2022 as the “referendum” for the Kherson region to join Russia was approaching.

The Stepanskyis contacted an acquaintance who took people out of the region via Vasylivka, in the Zaporizhzhia region, the only checkpoint between Russian-occupied territory and the area controlled by Ukraine.

Oleh was lucky. He made it unscathed and was reunited with his family in the Ternopil region of western Ukraine. His parents were relieved that their son was safe.

Mykola says they experienced the so-called “referendum” first hand in September. Campaigners armed with guns came to the family home, urging them to vote. Mykola and Lyda refused. “Why bother participating in this disgraceful farce?” Mykola asks.

A hole in the heart

Oleshky had been subjected to heavy shelling from the first days of the war, and that only intensified when the Ukrainian army liberated Kherson in November 2022. Oleshky is surrounded by forest, ideal for Russian soldiers to hide out in. From here they fire at Kherson, and the Ukrainians fire back.

For most of that time, the Stepanskyis, like their neighbours, stayed in their basement. On 28 December 2022, they received a message from Oleh: he had read on Telegram that there had been an air strike on Oksana’s street. The report was true.

Oksana’s husband, Leonyd Pavlyuchenko, told the Stepanskyis that their daughter had been killed by a shell, shards of metal piercing her body near her heart. After the shelling, FSB officers, soldiers and pro-Russian journalists turned up in their yard.

“First we were told that our daughter’s death was caused by Ukrainian shelling,” Mykola said. “But we heard where the firing was coming from. There was a tank not far away, firing randomly at houses.”

Three shells landed a short distance away, and the fourth exploded in the yard, right next to Oksana. The hole in her ribcage was so large you could put your hand inside it, her father said.

Oksana was buried on 29 December 2022. Many locals gathered in the ruins of the yard. Nobody would have thought that there were still so many locals left in Oleshky, which was being shelled from all sides on a daily basis.

Seeing that people had gathered for a funeral, Russian soldiers rolled out a missile launcher, set it up about a hundred metres away and started firing over people’s heads towards Kherson. Mykola thought that people would run away in fear.

“But no, not a single person left, so great was the hatred towards those who brought sorrow to our homes, to our country,” says Mykola.

The flood

After Russian forces captured the Kakhovka hydroelectric station, there was constant talk of it being blown up. To stay in Oleshky meant taking your life in your hands, but Mykola had no intention of leaving, whatever happened — the bee farm and the bees were like family.

The Kakhovka dam was eventually blown up on 6 June 2023. The occupiers didn’t evacuate Oleshky. They didn’t even warn people about the flood.

Perhaps the Russian troops didn’t know about the explosion themselves, Mykola says.

“I saw videos later on local channels of Russians sitting in trees, and the corpses of their soldiers floating down the Dnipro towards the sea. People said that many of the soldiers drowned, as many as a thousand. It shows that the Russian leadership not only doesn’t care about the civilian population, it doesn’t even care about its own soldiers — it is absolutely merciless.”

On the morning of 6 June, the Stepanskyis saw the water rising higher and higher.

“I hurried to the bee farm,” Mykola recalls. “I was on the verge of tears, to be honest, and I kept saying: ‘What can I do for you, my bees? I can at least open the lids of the beehives for you.’”

Mykola and his wife abandoned their house, which was filling with water, and went to the apartment building where their son had lived. They sat out the entire period of the flood there.

All the phone lines were out, and for a few days the Stepanskyis had no idea what had happened to their grandson and son-in-law. But then there came a sudden knock at the door: it was Slava and Leonyd. They said that their house was under water, with only the chimney left above the surface. They had sat out the flood in the attic of their neighbours’ two-storey home, and a boat had come to rescue them.

Seeing that his relatives were safe, Leonyd left his son with them and set off to help. He managed to find a boat and called on a neighbour to assist him, and for several days they rescued people from roofs and attics and took them to dry land.

Leonyd said that rowing the boat was made difficult by the sheer number of corpses in the water and that they had to do their best to manoeuvre around them. Nobody was focused on the dead at this point. Every effort was concentrated on rescuing as many of those who had survived as possible.

“A woman who had recently given birth to twins lived nearby,” Mykola continues.

“I don’t know where her husband was, but for some reason she was alone with her children during the occupation. When the water began rising, she tried to climb up into the attic with her two babies, but she slipped and fell back into the water with them. They all drowned.”

Mykola says that according to a local friend and doctor, 1,560 people drowned in the flood in the Oleshky district alone, but that’s simply the number of bodies that were recovered in the immediate aftermath. Bodies that were swept into the river could not be counted. Neither the Russian nor the Ukrainian authorities have told the truth about the number of people who drowned, while the number of animals that drowned cannot even be guessed at.

Departure and return

The water took 10 days to recede from the Stepanskyis’ home, while it took over a month for Leonyd and Slava’s house to become accessible again. When Mykola and his wife returned to their yard, the trees were full of bees and the beehives were turned over and broken. The water had upended them and swirled them around, like a whirlpool. The young bees and queens had drowned and started to rot — the stench was terrible. And without the queens, of course, the adult bees also died.

The doors to the house had expanded, and had to be opened with a crowbar. Nothing inside had been spared: everything was covered in black slime, the walls and ceilings had collapsed, all the furniture was misshapen, the sofas had been shifted by the water pressure, and the large, heavy fridge lay on its side. The flood had also damaged their new car beyond repair, as well as their son’s motorcycles, and all the equipment and tools that Mykola had used for beekeeping.

Having lost everything, the Stepanskyis decided to leave Kherson for Europe. On 17 June, the family took a minibus to the border between the Kherson region and Crimea. They got through border control without any issues, although they had worried for their grandson and son-in-law. They were lucky that at that moment many people were leaving areas affected by the flood via Crimea, and the border guards were extremely busy.

After the border checkpoint, a large bus was waiting for them and other passengers. They paid $350 each and set off for a three-day journey across Russia, stopping only for food and toilet breaks at petrol stations.

Upon reaching the Latvian border at noon on 20 June, the passengers got off and the bus drove away.

After waiting for 12 hours, the guards began calling on the Ukrainians to pass the border inspection, 10 at a time. When the Stepanskyis’ turn came, Mykola was let through without any additional questions, because of his age. His wife, son-in-law and grandson had to fill out forms, providing details of everywhere they had lived since birth. Lyda wrote “USSR” in big letters, which drew a smile from the border guard.

“The border guards asked where our children were, but we didn’t tell them that our daughter had been killed by one of their shells. We said that they had stayed at home,” Mykola recalls.

The border guards inspected their personal items and let the elderly couple through, but Slava and Leonyd were taken away for additional questions. Several hours passed. Leonyd came back, but Slava didn’t.

“We were in such a state of fear the whole time, I can’t describe it in words,” says Mykola. “In the morning Slava came back to us, exhausted. Lord, we were so happy to see that he was alive and free. He didn’t say much. He’s been quiet ever since that first day on Antonivskyi Bridge, but he did say that they had made him a lot of promises: an apartment and a job with a good salary if he stayed in Russia. But he wouldn’t relent and eventually they let him go.”

A full 24 hours after they got off the bus, the Stepanskyi family crossed the Latvian border. From there they took another bus to Poland.

The Stepanskyis were given a warm welcome at the refugee camp in the Polish capital, Warsaw. They could finally eat proper meals again, and the food was delicious. For two days, they ate and slept in the camp. Mykola got a call from his brother who had been living in Europe for years, inviting them to stay, but he and Lyda decided that they wanted to live in Ukraine, and so they set off to join their son’s family in Ternopil.

“Our grandson stayed in Europe,” Mykola said. “We were afraid he would be called up to the army. Perhaps people will judge me, but let me put it like this. This war has taken a great deal away from us. I couldn’t care less about the material losses, but nobody can give us back our child, so at least Oksana’s son should be allowed to live. Slava is our daughter’s only legacy. Oksana’s death has been a constant source of grief for us for a year.”

“They say that time heals, but it doesn’t heal at all. Not a day has gone by when my wife hasn’t cried for our murdered daughter. Not a single day!”

“When the war broke out, nobody believed that people would really kill each other, that our children would be brutally tortured,” Mykola says. “Russian propaganda used to say that we were brothers, one people. But how can we be brothers after this? The war is like a litmus test showing people’s true worth.”