The final turnout for Russia’s presidential election in occupied Kherson was 83.87% according to polling data released on Sunday. Marina Zakharova, head of the regional electoral authority, said that with 100% of votes counted, incumbent Russian President Vladimir Putin had secured 88.12% of the region’s vote and that no irregularities had been reported.

According to official data provided by the Russian-appointed authorities in the region, there were 61 polling stations operating in divided Kherson and a further 300 mobile teams dispatched to help people vote in or near their homes.

“They might have been somewhere, but they definitely weren’t here,” Andriy, 45, from the Russian-controlled town of Oleshky, told Novaya Gazeta Europe. He said that not many people would risk coming down the “road of death” to Oleshky with their propaganda as it is under constant surveillance and is frequently shelled by Ukrainian forces.

“The only cars that come here are carrying food and industrial goods from Hola Prystan,” he added.

Andriy maintains that if the election went ahead at all in Kherson, then it was only somewhere deep within occupied territory. There was no early voting in Oleshky either. “There’s no point faking an election when there’s daily shelling, or going to vote somewhere where they’ll declare a 100% tally for Putin anyway.”

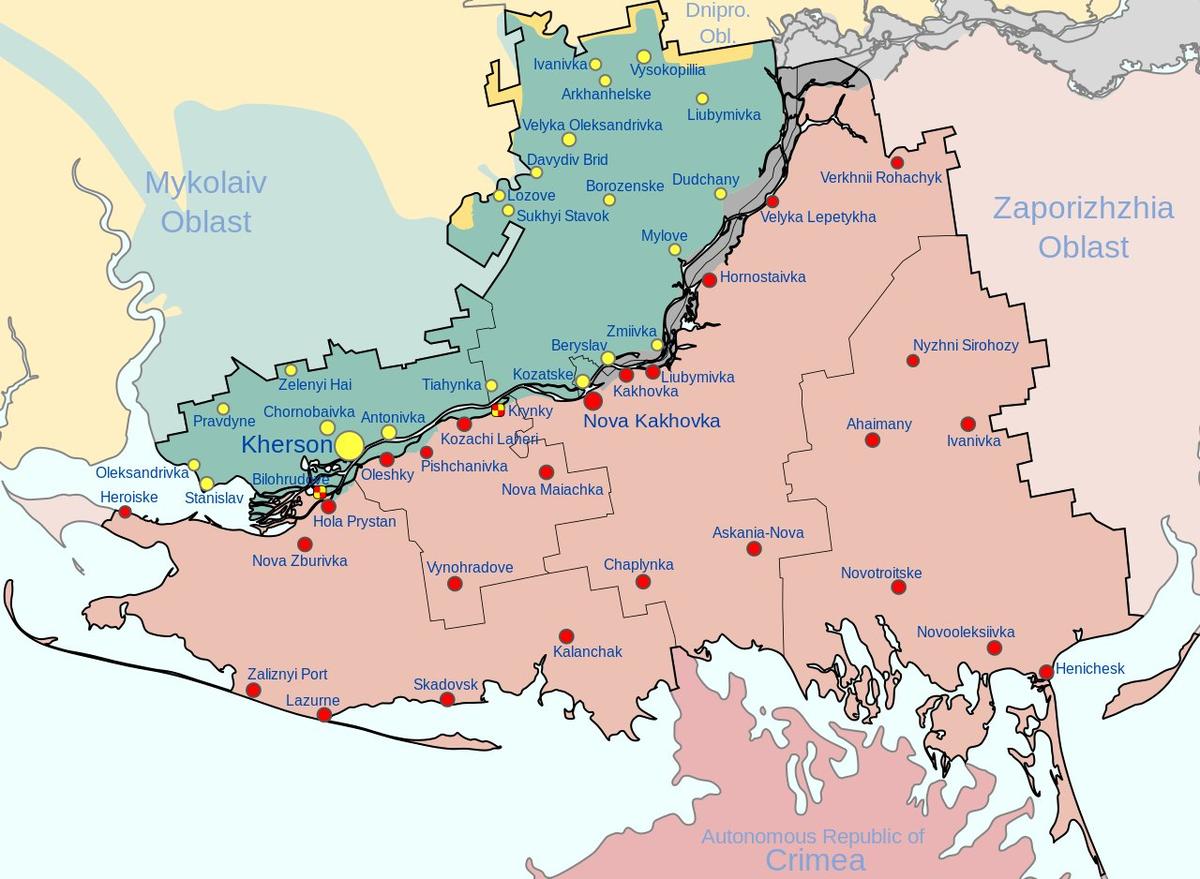

A map of Ukraine's Kherson region, showing Russian-occupied territory on the left bank of the Dnipro River in red and the Ukrainian-controlled right bank in green. Source: Wikipedia

Andriy and his family still have Ukrainian passports, and refuse to accept Russian benefits and pensions. Their Ukrainian pensions cover food. The only thing that really worries him is the news that the local authorities will start deporting Ukrainians who don’t have Russian passports from 1 July.

“I have no idea how they’re going to do it,” says Andriy. “How will they get people out of the occupied areas? Run after us with machine guns while Ukrainian drones fire at them?”

Andriy added that Russian nationalists had already suggested stringing up or shooting any Ukrainians still hoping for the Armed Forces of Ukraine to arrive and liberate them.

A drone found on the roof of a building that was reportedly being used as a polling station in Nova Kakhovka, 16 March 2024. Photo: izbirkomherson / Telegram

‘They pointed and I checked the box’

The election did go ahead, though, in the inland villages of Brylivka and Nova Maiachka, both about 30 kilometres north of Kherson’s Black Sea coast. On the morning of 15 March, local propaganda outlets published pictures and clips of happy voters, but by the afternoon news got out that a rocket had hit the Brylivka polling station, injuring voters. A drone also hit a polling station in the town of Kakhovka.

Shortly before the incident, Volodymyr Saldo, the Moscow-installed governor of the Kherson region, said that people in the towns of Kakhovka and Nova Kakhovka had been queuing up to vote from 7am, even though polling stations only opened at 8am. In view of the subsequent attacks, it isn’t clear why voters were in such a rush — was it a burning desire to fulfil their civic duty or simply to get it over and done with quickly to get as far away as possible from an unsafe place?

“Everyone has to go to the polls. It is everyone’s civic duty, and they are obliged to do so. Let’s hope that the war ends soon and everything will be fine,” the pro-Russian TV channel Tavria quoted a local woman as saying.

“They came to our boarding house on the first day of voting,” Nadezhda told Novaya Gazeta Europe before the official results had been announced. Nadezhda, a 75-year-old from the village of Kardashynka, has been living in temporary accommodation in Zaliznyi Port since the summer of 2023. “I asked who the youngest person on the list was. They pointed and I checked the box. I don’t even remember the candidates’ surnames. It doesn’t matter what their names are or who they are, as long as I don’t vote for Putin. But knowing the Russians, there’s no doubt they’ll declare Putin the winner. I didn’t want to be part of this circus at all, but there was no way round it. They told us that if anyone refused to vote, they’d be thrown out, along with their things. And I have nowhere to go. I lost everything in the flood.”

‘They will vote on our behalf as they see fit’

“As a law-abiding Russian citizen, I am voting for the bright, beautiful future that awaits us in the Kherson region,” says Maria from Zaliznyi Port in one of many similar propaganda videos broadcast on Saturday. Residents of the town of Hola Prystan immediately recognised the lady draped in fur as a former employee at the local welfare office.

“It’s sad seeing familiar faces justifying this bloody war for money, but I hope that the Ukrainian legal system will come down hard on them one day,” says Natasha, 41.

“Not a single one of my relatives or close friends voted in these so-called ‘elections’. There wasn’t even a polling station. I noticed a mobile group visiting several elderly people and those with mobility issues in early March, but there really aren’t many of them.”

Natasha says most people in the town ignored the election. There were no billboards and there was no campaigning. She is convinced that not everyone even knew there was an election. Hola Prystan is now considered hard to reach, so the authorities don’t pay it too much attention.

Vera, a 68-year-old from the town, agrees. She says that there are just five residents remaining on her street, and there are barely 50 people in an area that was once home to about 3,000 before the war. Vera and her pensioner neighbours applied for Russian passports in the winter, having been warned that without them they wouldn’t be eligible for their monthly pension of 10,000 rubles (€99). There are no banks or ATMs in the town. Indeed, the town itself is almost gone.

“We basically have nowhere to go, so we had to accept this red passport to avoid starvation,” Vera says with a sigh.

“I know that in villages beyond the 15-kilometre zone, doctors won’t even provide medical care to people who still have Ukrainian ID cards. Things are easier here. We don’t have doctors, not even a paramedic, so nobody cares about your passport, except for the people who bring our pensions. Did the news say there were elections here? Seriously? The town is in ruins. How could you hold an election? They already have our data. We had to provide it when applying for our passports. They will vote on our behalf as they see fit.”

A polling station in the Kherson region, 17 March 2024. Photo: izbirkomherson / Telegram

‘Nobody asked our opinion in Ukraine or in Russia’

The situation is no better in villages further from the front line. One man in the small village of Chornomorske, near Zaliznyi Port, told Novaya Gazeta Europe that they had received no state benefits at all — pensions, disability payments, child welfare — since the start of the year, even though they were made to apply for Russian passports last year. He says there was no election in the village, but a mobile team did visit the elderly and disabled in early March. But last weekend, when the news was full of video footage from polling stations, silence reigned.

In the port town of Skadovsk, classes were cancelled at a school that was used as a polling station, but elsewhere the children studied as normal. The local authorities said there was an act of sabotage at a polling station in the town; somebody placed an improvised explosive device in a bin by the entrance, and it exploded. The incident did not disrupt the voting, however, with the polling station functioning as normal.

“There was an event in Skadovsk to do with the elections. There was music. There were a lot of people on the street,” says Iryna, 54, who lives in the surrounding area.

“But there was no campaigning in our village. They didn’t even put posters on the shop door. There weren’t any lotteries or draws here either, like there were in other parts of Russia. And there was no election in the village.”

Iryna, who worked for the occupying authorities for over a year and was one of the first people on the left bank of the Dnipro to receive a Russian passport, nevertheless admits she had no desire to go to the polls anyway, so it was “just as well” there was no election in the village.

“I don’t even care who the candidates are,” Iryna said. “Nobody asked our opinion in Ukraine or in Russia. The one who steals the most votes will win. I gave up on the idea of voting five years ago. I didn’t like the candidates. Whoever the authorities want to win will win. There’s no way round that in this country.”

The electoral register in the “new territories” supposedly includes all the adults officially resident in the occupied regions of Ukraine in early 2022. However, analysts agree that the census was inaccurate in these regions even before the outbreak of the war, and that the level of inaccuracy has reached an entirely different level since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. Indeed, demographers estimate that the figure of “4.6 million official voters is about 80% higher than the actual adult population living there”.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]