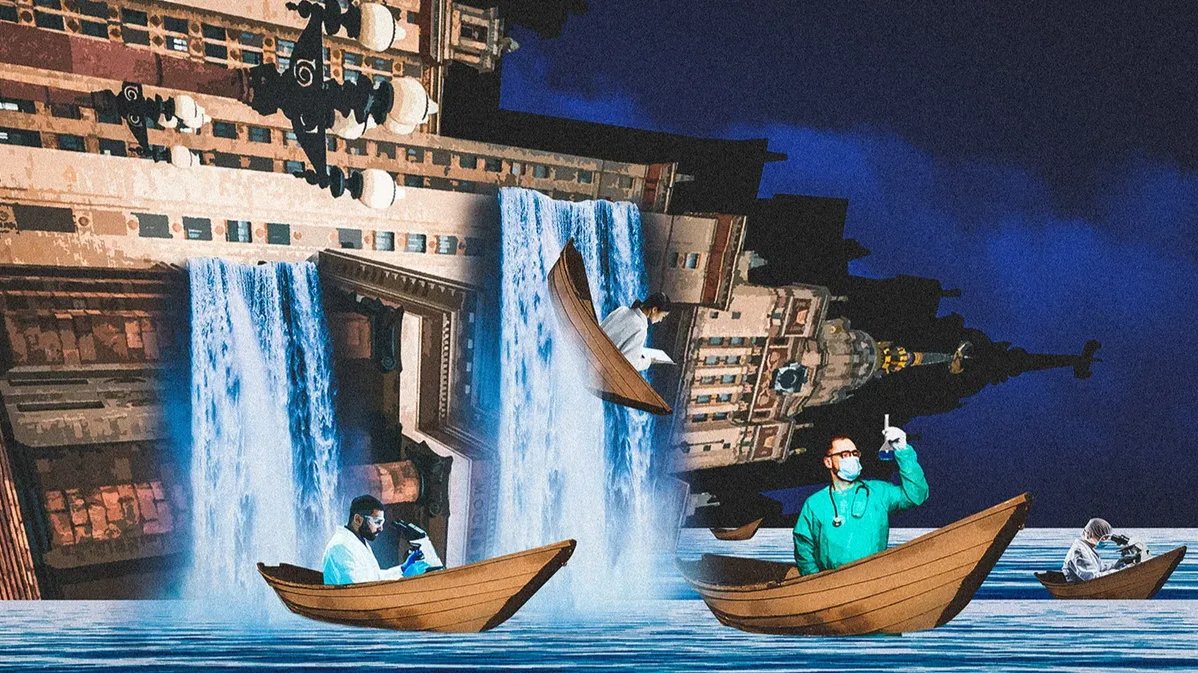

The war in Ukraine and the ensuing isolation of Russian scientific institutes have led many researchers to look for opportunities abroad. By analysing the publication of scientific papers over the past two years, Novaya Gazeta Europe estimates that as many as 2,500 scientists have left the country since the war began.

The Russian government’s attempts to monitor the scientific community’s international contacts, as well as the recent string of high treason cases against Russian physicists, may have only added fuel to this particular fire, with hundreds of Russian researchers choosing to leave their home country to avoid additional scrutiny.

In a study published in August, Novaya Europe looked at the staff lists published on Russian university websites before and after the war to discover that at least 270 scientists left Russia in that period. Our latest analysis of publication metrics shows that this number could actually be far higher.

Assessing scientific migration

To evaluate publication activity, we used ORCID, an international database created in 2012 to identify researchers that currently holds data on over 20 million scientists worldwide. Major Russian universities have made all academics publishing research register with ORCID and have been known to create accounts for them in bulk: by 2020, over 5,000 scientists were being added to the database every year.

As of October 2023, ORCID listed over 130,000 scientists working in Russian institutions. In major universities such as Moscow’s Higher School of Economics (HSE) and the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT), 20% to 30% of all researchers are registered with ORCID (including teaching staff and administrative personnel).

Other key universities with a significant ORCID presence include the Moscow State University (MSU), the Kazan Federal University (KFU), and the St. Petersburg State University (SPbU).

Analysing Russian ORCID accounts can help us establish how many scientists left Russia after the invasion of Ukraine, although there is usually a time lag of six to 12 months, as people tend to wait some time before updating their “place of work” status.

From 2012 to 2021, the share of Russian researchers changing affiliation remained at a steady 10%. In 2022, the number increased sharply to 30%. This means that more than 600 researchers have left Russia since 2022, while the share of those choosing their next job abroad has tripled.

If we take into account that people tend to wait for a year before updating their place of work, the total number of those who have severed ties with Russia can be put closer to 1,600.

If we include those who have been dismissed from a Russian organisation, added a new country of residence without specifying their workplace, or deleted records of employment in Russia, then we get an even higher number — 900 people for the years 2022-2023. This means that, by the most conservative estimates, a total of 2,500 researchers have left Russia since the war began.

Young Einstein

One researcher who requested anonymity told Novaya Europe that scientists have been leaving Russia since the outbreak of war not only due to fear of persecution, but for pragmatic reasons. As Russia is under Western sanctions, it has become much more difficult to do research, to join international collaborations, get published in scientific journals, and obtain access to necessary equipment.

Having analysed ORCID data, we identified several dozen academics who deleted references to work they did in Russia after 2021, though it’s impossible to say whether this was an attempt to avoid sanctions or an expression of their political stance. Scientists and experts interviewed by Novaya Europe pointed out that while the information provided in a scientist’s ORCID profile should not affect grant applications and job offers, universities outside Russia often frown upon a researcher’s previous connection with Russian scientific institutions — even those that have not been subjected to sanctions.

Another scientist who has left Russia and who spoke to us on condition of anonymity confirmed that there had been a noticeable increase in the number of young researchers deciding to leave the country. Top graduates of master’s and postgraduate programmes now often decide to pursue careers abroad early on in their studies, while graduates of 2022 and 2023 are already actively leaving Russia.

Losses of Moscow universities

Moscow universities and research centres (including MSU, HSE, Skolkovo, MIPT) have been most affected by the post-war “brain drain”, accounting for 23% of all scientists who have left the country.

These losses may seem small compared with the overall number of employees in academia — a mere 1-3% for top universities. However, as the figure only includes scientists who had already updated their ORCID profiles with a new workplace, the real number is likely to be higher.

Also in flux are the destinations.

Before the war, the top three destinations for Russian scientists were the USA, Germany and the UK. Israel jumped to third place shortly after the war began to reflect the 175% leap in the number of researchers moving there. The number of scientists moving to former Soviet republics for which Russians enjoy visa-free travel — Uzbekistan, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan — also grew significantly after the outbreak of war. While the UK, France and the USA still lead the ranking in absolute terms, the flow of scientists to all three countries has nevertheless decreased by over 20%.

What the future will bring

As many scientists interviewed by Novaya Europe pointed out, it was clear before 2022 that Russia was experiencing a net loss of scientists.

The most catastrophic “brain drain” estimate was given before the war began by Nikolay Dolgushin, Chief Scientific Secretary of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He claimed that the number of highly qualified researchers leaving Russia increased from 12,000 in 2012 to 70,000 in 2021, though it wasn’t clear exactly how these figures had been reached.

Russia’s publication activity has been declining for several years now, falling to 11th place in the ranking of countries by number of international publications — the place Russia held back in 2016-2017.

Another Russian researcher in exile who spoke on condition of anonymity made it clear that it would be foolhardy to expect this trend to end any time soon. In the last 20 years, he said, people felt it was possible to do scientific research in Russia again, so some researchers returned, while others lived and worked between two countries. But now “this reputation has been lost”.

“When such things collapse, they cannot recover in a year or two. It will take another 20 years,” he added.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]