Last week, Moscow’s prestigious Higher School of Economics (HSE) dismissed one of its founders — Igor Lipsits, Doctor of Economics. The scientist has lived abroad in the last three years and has repeatedly chastised the Kremlin for its aggression against Ukraine.

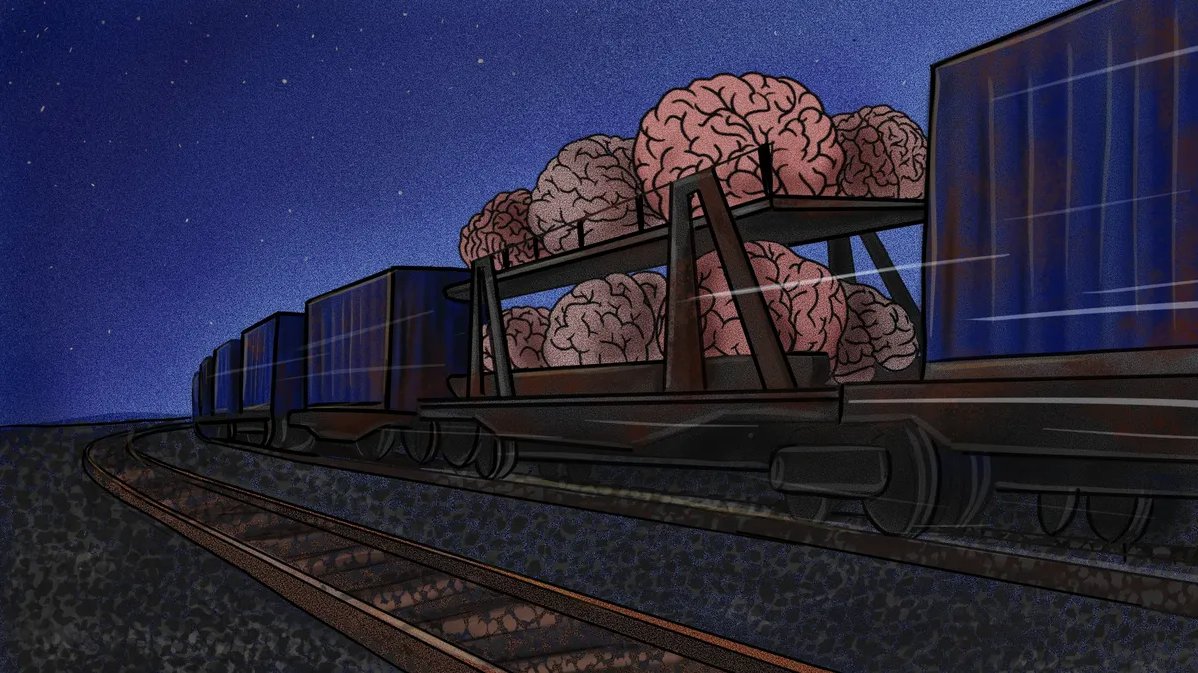

There are hundreds or even thousands of similar stories out there. Novaya-Europe has studied open sources to identify 270 university staffers, including professors and heads of institutes, who severed ties with Russia in the past 18 months. Let’s take a look at the toll the war is taking on Russian science.

Novaya-Europe has identified at least 270 academic staff members of Moscow and St. Petersburg’s high-ranking universities who have left Russia since the Ukraine war broke out. Among them, 195 are considered Russian scientists, while the rest are foreigners.

The HSE tops the list of the most faculty members who have stepped down with 160, followed by St. Petersburg State University (35) and the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (32).

This is a very conservative estimate, one that only includes the cases that we could verify through open sources. In reality, this number can be many times higher. We also excluded the scientists who continued to work in Russian universities after their relocation.

Half of the Russian scientists who left the country publicly opposed the invasion of Ukraine: they posted online and signed an open letter against the war.

In the past 18 months, at least 21 Russian economists, 27 computer scientists, 34 physicists and mathematicians, 15 biologists, and 17 philologists left the country.

Most of them are acclaimed scientists. Many had ties to foreign universities. Up to a quarter of them have the citation H-Index of 10 or higher, which indicates a successful career for scientists with 20 years of research experience.

HSE in exile

The past two years saw the Higher School of Economics — a university that Vladimir Putin referred to back in 2010 as “cutting-edge in every respect” — slide down in the global rankings by almost 100 spots (from the 305th to the 399th).

The HSE took a turn for the worse just after the 2019 Moscow protests, when citizens spilled onto the streets to take a stand against the rejection of independents seeking to run in the Moscow local elections. The university then adopted an ethics code for its staffers, effectively banning them from speaking out about political issues. This period also marks the first “purges” among the HSE staff.

In 2020, the university axed 28 employees. Among them were Associate Professor of the School of Philosophy Kirill Martynov (currently Editor-in-Chief of Novaya Gazeta Europe) and law faculty Professors Elena Lukyanova and Irina Alebastrova, who both objected to the proposed amendments to the Russian constitution, which were subsequently adopted in 2021.

The HSE administration was putting pressure on its staff even before the war. In 2021, the institution received a new rector who launched a gradual change of faculty members.

“As his team grew, the pressure within the university was becoming more and more systemic,” Ilya Inishev, Doctor of Philosophy who worked in the HSE from 2010 until 2022, told Novaya-Europe.

Last year, Inishev signed the scientists’ letter against the Ukraine war and supported Kyiv on his personal Facebook page on a number of occasions. In late December, he was dismissed due to the “serious damage” his comments “inflicted on the university’s reputation”. Inishev then moved to Germany in April 2023.

The HSE also shut down at least six departments in the past 18 months. Former HSE Professor Mikhail (name altered) who left Russia after the mobilisation announcement says that at some point “all PhDs, except for one, all senior researchers, and foreigners” left his department. The unit was ultimately disbanded.

The prestigious university lost at least 150 academic staff members following the Kremlin’s decision to invade Ukraine according to Chicago University Professor and economist Konstantin Sonin. Sonin also used to work at the HSE: he was fired in the summer of 2022 and a year later placed on the wanted list in Russia for spreading “fake news” about the Russian army.

Moreover, the HSE drastically slashed cooperation with foreign universities, which it was famous for in the past. HSE students could participate in dual-diploma programmes with esteemed foreign universities. Most of these former partners are now located in “unfriendly” states.

Novaya-Europe has calculated that the HSE only has 11 dual-diploma programmes left out of 61. Most faculty members from “unfriendly” countries have tendered their resignations. In total, Russia has lost 75 foreign professors.

Support independent journalism

Unauthorised liberalism

The Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences, a division of St. Petersburg State University, also drew scrutiny for its liberal ways of education. It was founded jointly with the US Bard College and became the first faculty in Russia that allowed students to independently choose courses to attend.

In late 2020, head of the faculty and ex-Finance Minister Alexey Kudrin suggested turning it into an independent entity. It never happened, while Bard College was designated as an “undesirable organisation” six months later.

In May 2022, the university was targeted by an “extremism” inspection. Law enforcers discovered “highly ideologised subjects” and “inconsistency with academic rigour” in the faculty curriculum.

Novaya-Europe calculates that 30% of the academic staff either resigned or were sacked from the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences, while 53 of its 359 courses were removed, including Gender Studies, Economy and Religion, New Age Political Philosophy, and others.

Relocation havens

Germany is the most popular post-war relocation destination for Russian scientists: at least 29 of faculty members from our list have found refuge there. Meanwhile, 42 more have moved to the US and Israel.

Three German universities offered help to Ukrainian and Russian scientists in relocation: Universities of Cologne and Bonn as well as Max Planck Institute for Mathematics.

However, not all Russians manage to carry on with their careers abroad.

“It is almost impossible to fit in a different academia after arriving with thousands of other repatriates,” says Maria (name altered), Associate Professor and Doctor of History from the HSE. Maria left Russia for Israel in March 2022. “You can find separate projects, which is what many are trying to do now,” Maria says.

Hundreds of Russian social and humanities scientists have moved to Israel, judging by the number of an informal chat of relocated Russians from scientific circles.

Drones over higher maths

Scientists first raised alarms about the academic brain drain from Russia back in 2009, writing an open letter to the president. The flagship project meant to raise the status of Russian science and reverse the “drain” was the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (Skoltech).

Skoltech was founded in 2011 in partnership with MIT and was doing well in the beginning: it was the only Russian university to feature in the top 100 “young” universities in the world.

Nowadays, this success is almost completely gone. Novaya-Europe has discovered that almost one-third of Skoltech’s faculty members have resigned, while the iconic US research institute cut ties with its Russian counterpart.

In total, 35 professors — all with US passports — have stepped down from their posts in Skolkovo. The rector noted the faculty members resigned in one fell swoop in August 2022.

Mathematician Yevhen Makedonsky is one of them. Born in Ukraine’s Melitopol, he did research work in Russia before the war. Having obtained his PhD in the HSE, Yevhen spent more than five years in Skoltech studying representation theory. The mathematician saw that it was time to go after 24 February, when Russian tanks were assaulting his hometown.

He received an offer from Max Planck Institute for Mathematics and managed to escape Russia in late February 2022. “I realised that the Russia I knew was over, the Third Reich has begun,” this is how he described his last day in Moscow on Facebook a year later.

The scientist emigration from Russia was becoming more and more prominent gradually. The Russian Academy of Sciences estimated that the number of scientists who left Russia had increased by five times by 2021 compared to 2012. At the time, the Kremlin did not notice “anything tragic” about this but did a sharp U-turn after the war began: Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov described “creation of comfortable work conditions” for scientists as a task for the country, while Vladimir Putin moved to reinstate the mega-grant programme for researchers.

The following projects were backed by Russia this year: a vertical take-off drone, Russia’s answer to Tinder dubbed Fall in Love Again, and a monograph about the economic effects of establishing the Union State of Russia and Belarus.

Philosopher Ilya Inishev notes that the situation in Russia’s academic circles is unlikely to change for the better any time soon. He believes that the repressions against the scientific community will only get more persistent even if the war is concluded. “I am afraid that scientists will not have any sensible reasons to return to Russia, save for extraordinary circumstances.”

With contributions from Katya Orlova, Katya Kobenok, Elena Popova, Natalya Kuraeva, and Marina Kiryunina.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]