Dmitry Skurikhin is a 49-year-old entrepreneur, activist, former municipal deputy, and father of five from the village of Russko-Vysotskoye outside St. Petersburg. He is also the first person in Russia sentenced to jail time — rather than simply fined — under recent legislation that criminalised “discrediting the Russian army”.

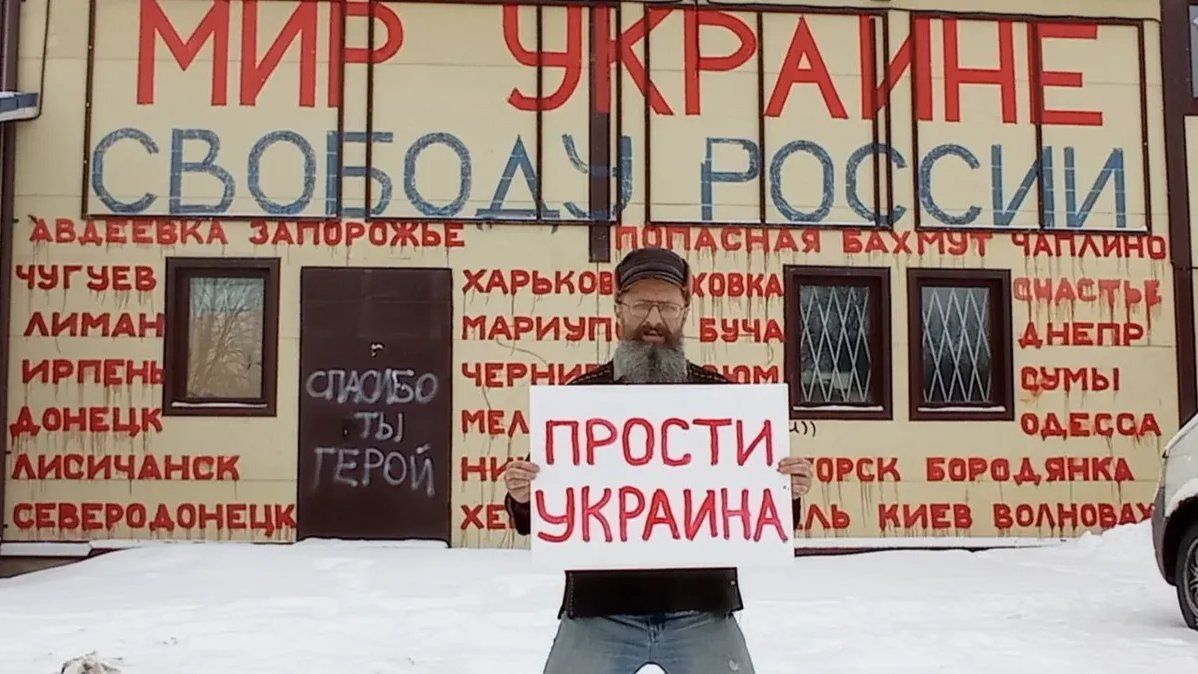

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Skurikhin has repeatedly spoken out against it, condemning the actions of the Russian authorities and expressing his support for Ukraine. He did this mainly by covering his two village shops in anti-war placards and slogans, including the names of Ukrainian cities devastated by the Russian army alongside calls for peace in Ukraine and freedom in Russia.

In August 2023, Skurikhin was sentenced to 18 months behind bars. Having been in pre-trial detention since he was arrested in February, he is now due to spend the rest of the year in prison.

‘The bravest man in the Leningrad region’

Locals who share the same political views as Skurikhin but are afraid to express them so openly call him “the bravest man in the Leningrad region.”

Skurikhin began his entrepreneurial career in the late 1990s, when he opened two food shops. In the early 2000s, he entered politics and became the only independent municipal deputy in Russko-Vysotskoye, where he had to compete with nine members of the ruling United Russia party.

“Since then, he has been passionate about integrity in government, justice, and the common good," says Skurikhin’s wife Tatyana, with whom he has lived for 25 years.

Dmitry Skurikhin with his wife Tatyana outside the court in Russko-Vysotskoye. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov for Novaya Gazeta Baltic

Until 2014, he was incredibly popular in Russko-Vysotskoye — but Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea changed everything. The village, much like Russian society, was divided, and Skurikhin’s condemnation of the annexation aroused suspicion in many local residents. Things became even more difficult after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, when he openly voiced his support for Ukraine.

Skurikhin first publicly spoke out against the war on 6 March 2022, when he declared in a video on his Telegram channel: “I, an active citizen from the St. Petersburg region, protest against this war. Putin and his gang are a cancerous tumour that has engulfed all of Russia and is now spreading its metastases in Ukraine and around the world. Russians, let’s stop this disease, stop this plague! No to war in Ukraine!”

In May 2022, he was charged with “discrediting the armed forces of the Russian Federation” and fined 45,000 rubles (€650 at the time).

Skurikhin’s fine did not stop him, however. In August 2022, he made a banner that said: “Russian society, wake up! Stop the insane, false, vile, fratricidal, shameful special military operation!” and hung it on the outside of his shop. On 22 September 2022, the police opened the first criminal case against Skurikhin for “repeatedly discrediting the Russian army” and searched his premises.

Photo: Skurikhin family

On 24 February 2023, exactly a year after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Skurikhin made a new placard with “Sorry, Ukraine” written in red on a white background, and got on his knees in front of his shop with it. His daughter Ulyana photographed her father and sent the photo to the media. Within minutes, the police had arrived, confiscated the placard, opened a second criminal case against Skurikhin, and trashed the premises as they searched it again. Skurikhin himself was detained and placed in custody, and, six months later, sentenced for the two placards.

“I exercised my right to freedom of speech and to say things as they are,” Skurikhin said in his closing speech in court. “I am certain that my placard remains relevant. I am ready to prove everything written on it and any epithet used to describe the ‘special military operation’. And life will confirm that I am right.”

Home alone

Since August, the Skurikhin family’s small two-story house in Ropsha, a tiny village of around 800 people not far from Russko-Vysotskoye, has been deserted. First, Skurikhin was arrested. Then, Skurikhin’s wife took the decision to send her two youngest daughters to boarding school. Without Skurikhin she had been taking care of everything around the house, as well as running his business and doing her own job.

Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov for Novaya Gazeta Baltic

But the family didn’t ask anyone for help after Skurikhin’s arrest, nor when his sentence was announced. Those who cared reached out and supported the family unprompted, Tatyana says, adding: “Thanks to them, I managed somehow to get by when I was left alone with the children after the searches, in a trashed home with no money to my name."

Tatyana often thinks back to a particularly difficult time in October, when she received both a list of what Dmitry needed and a transfer of 5,000 rubles (€50) simultaneously.

“At that time, I was able to buy everything Dmitry asked for: trousers, gloves, medicine,” she says. “I was only able to buy it because of the money I received.”

Tatyana still finds it hard to accept that, in the village where the Skurikhins had lived for so long, so few people even attempted to support or reassure them. Tatyana’s work colleagues reacted similarly, limiting their communication with her to “hello” and “goodbye.” Tatyana believes that people are guided by two emotions — fear and indifference.

“What amazes me the most is the absolute indifference and calmness of the people in the village and my colleagues at work,” she says.

‘I need peace’

“I always find it funny when they call Skurikhin a ‘businessman’,’‘ Tatyana says with a smile. ’I remember our little village shop in Yagelevo, which brought more problems and losses than it did income.”

Yagelovo is a village of 1,500 people. More of a kiosk than a store, Dmitry’s shop stands out against the grey of the surrounding buildings thanks to the message painted in white on its slate roof: “I need peace.”

The shop sells household items and groceries. In two hours, the only customer is a boy coming in for some bread.

Dmitry Skurikhin’s shop. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov for Novaya Gazeta Baltic

“We don’t have fewer customers now. We never had many in the first place,” says a shop assistant, reluctantly looking up from her book, when asked whether Skurikhin’s conviction affected business. “No one cares about it — about his crimes or his opinion. Here, all anyone’s bothered about is peace at home.”

With its population of around 5,000, Russko-Vysotskoye is a district centre by local standards, but it’s also deserted. Ask anyone, though, and they know Dmitry Skurikhin — if not by name, then by his actions.

Skurikhin started writing slogans and hanging placards on his shop after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. The earliest ones included “Peace for Ukraine” and “Freedom for Russia.” Later he began adding slogans condemning the murder of politician Boris Nemtsov, criticising Vladimir Putin, and calling for the release of political prisoners. In 2022, Dmitry painted the names of Ukrainian cities brutalised by the Russian army in red on the front of the shop.

Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov for Novaya Gazeta Baltic

Konstantin, a local pensioner waiting impatiently for the clock to strike 11 AM so he can buy beer, says of Skurikhin “He’s an idiot of the highest order and a traitor. He covered everything with filth.”

“Here.” Nastya, a young woman walking with her two-year-old son, points to the red-and-yellow wall of the two-story shop building. “He wrote: 'Peace for Ukraine!’ Peace for fascists! Can you imagine? He’s against Russia and against the special military operation. It’s a good thing they’ve imprisoned him and painted over it all.”

No prospects

A social worker in St. Petersburg, Tatyana earns around 60,000 rubles (€600) and is now the family’s sole breadwinner. Her job involves caring for 13 elderly people, each of whom she has to visit several times a week. As a result, Tatyana is rarely able to take time off to visit her husband at the detention centre or to deliver parcels to him.

Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov for Novaya Gazeta Baltic

For now, Skurikhin is in a pre-trial detention centre nearby. But soon he will be sent to a penal colony, and seeing him in person will be all but impossible.

On 17 November, the regional court reviewed Dmitry’s sentence. He had been optimistic that judges higher in rank than those in the local court who had sentenced him would see sense and acquit him.

“I didn’t have that hope, but he did,” Tatyana shrugs. “He was expecting his sentence to be reviewed because the punishment he received was the harshest possible. His lawyer also said he had a chance.”

But the regional court dashed these hopes. Unlike his son, Skurikhin’s father Nikolay had no expectation that the sentence would be reduced.

Dmitry Skurikhin’s sentence is confirmed by a St. Petersburg court on 17 November 2023. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov for Novaya Gazeta Baltic

“In an atmosphere like this, in a society like this, in a state like this, there can be no prospects for a normal person,” Nikolay says. “My son wants to defend his principles, but, as it turns out, they’re at odds with the convictions of the majority of people and the authorities. Fighting for a just cause is wonderful. But we see the result now.”

“Today you can go and enlist in the war and get 500,000 rubles (€50,000). That’s not even close to patriotism. It’s a completely different and very scary thing — the government is buying killers and sending them to war. No real patriotism can withstand that.”

This article was originally published in Novaya Gazeta Baltic.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]