Ukrainians are the third largest ethnic group in Russia, second only to Russians and Tatars, numbering 3.34 million people, or 3% of the population according to the most recent census, a figure that has remained stable for decades.

As ethnic Ukrainians are usually indistinct from ethnic Russians, with family names being the sole obvious indicator of non-Russian background, many ethnic Ukrainians in Russia nowadays prefer not to draw attention to their heritage.

However, the war has also served to motivate others to embrace their Ukrainian identity despite the repercussions that could have in a society where disloyalty to the government is seen as a moral failing.

Galina, St. Petersburg

Galina (not her real name) is in her early twenties and lives with her parents in the suburbs of St. Petersburg where she was born after her father moved there from Donetsk in Ukraine.

As we chat over WhatsApp in Ukrainian, I ask whether she would prefer to switch to her native Russian. “No, no!” she replies a little nervously. “Only Ukrainian. For me, this is a matter of principle”. Galina started learning Ukrainian on her own in 2017.

In January last year, Galina was invited by a friend to visit Kyiv for the first time. She had wanted to move to Ukraine, but at that point decided against staying and returned to Russia. She planned to go back to Kyiv and apply for a resident permit there at a later date.

“I hoped to return in six months at most. And then came the invasion. I was in shock. I was a Ukrainian in St. Petersburg, holding Russian citizenship. The war felt like my fault and responsibility.”

“On 8 March, I went to a coffee shop and ordered a pastry. I remember looking at it and thinking, what right do you have to eat delicious food when they’re bombing Kyiv and killing Ukrainians?” Galina recalls.

On the day of the Russian invasion, 24 February 2022, Galina took to the streets in a solitary protest with a poster reading “Stop the killing! No to war in Ukraine!”. She also joined planned protests, all the while looking for a way to get to Kyiv even as it was being bombed. Several times she was detained and released.

On 21 September 2022, Galina protested against mobilisation. She told the court that she felt no guilt. This time, she was jailed for 12 days.

“And you know, I felt better after that! It was a useful experience, joining the common struggle against an imperialist war of invasion. Previously, I had felt so tired and depressed,” she explains.

In the spring of 2023, Galina joined a small group of like-minded people who would take flowers to a monument to Ukrainian national poet Taras Shevchenko whenever there was news of Ukrainians killed in Russian missile attacks.

Flowers at the monument to Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko in St. Petersburg on 22 January 2023. Photo: Alexander Koryakov / Kommersant / Sipa USA / Vida Press

One day Galina was detained by police as she went to leave flowers and was not allowed food, water or a change of clothing for two days. It appeared to be something along the lines of a final warning: this is what things will be like if this gets “serious”.

Nowadays, Galina corresponds with Ukrainian political prisoners jailed in Russia. “I have to edit my letters carefully, think through every word so that the censors will let them through.”

“I have a fully formed worldview of a nationally conscious Ukrainian. But my passport is Russian,” she says.

Mykola, Murmansk

Mykola Malukha was born in the Ukrainian city of Kherson, but spent 19 years of his life in the northern Russian city of Murmansk, where he studied history in the 2000s.

Mykola confessed that at some point early on he had considered a career in the Russian security forces. But as time went on, his views changed and he joined the “youth wing” of the Ukrainian diaspora in Murmansk. The “youth wing” organised Ukrainian history-related events — one of them was the “Candle of Grief”, a demonstration marking the 20th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster.

A demonstration marking the 20th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster. Murmansk, Russia. Photo from the archive of M. Malukha

One of the events organised by Mykola, this time with the youth wing of the liberal Yabloko party, of which he was a member, was a discussion of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UIA), a Ukrainian nationalist formation founded during World War II. He put up leaflets with the slogan “Glory to the heroes of the UIA” around town to attract attention to the event.

The police raided the local Yabloko office shortly afterwards, demanding to know if the Ukrainian Insurgent Army was gathering there. Malukha was summoned by the Federal Security Service (FSB) and was told that his actions constituted extremism and calls to overthrow the state. They offered him a stark choice between going to jail and becoming an FSB informer.

Mykola chose the latter. From time to time, he would report back to the FSB on what was going on within the diaspora, mostly just copying information already publicly available on their website along the lines of: “We went to a summer camp and took language courses”.

In 2007, Mykola decided to return to Ukraine. “I realised that the period of relative liberalism was over. Russia was building a rigid vertical system, and any structures that were not controlled by the authorities would be dismantled.”

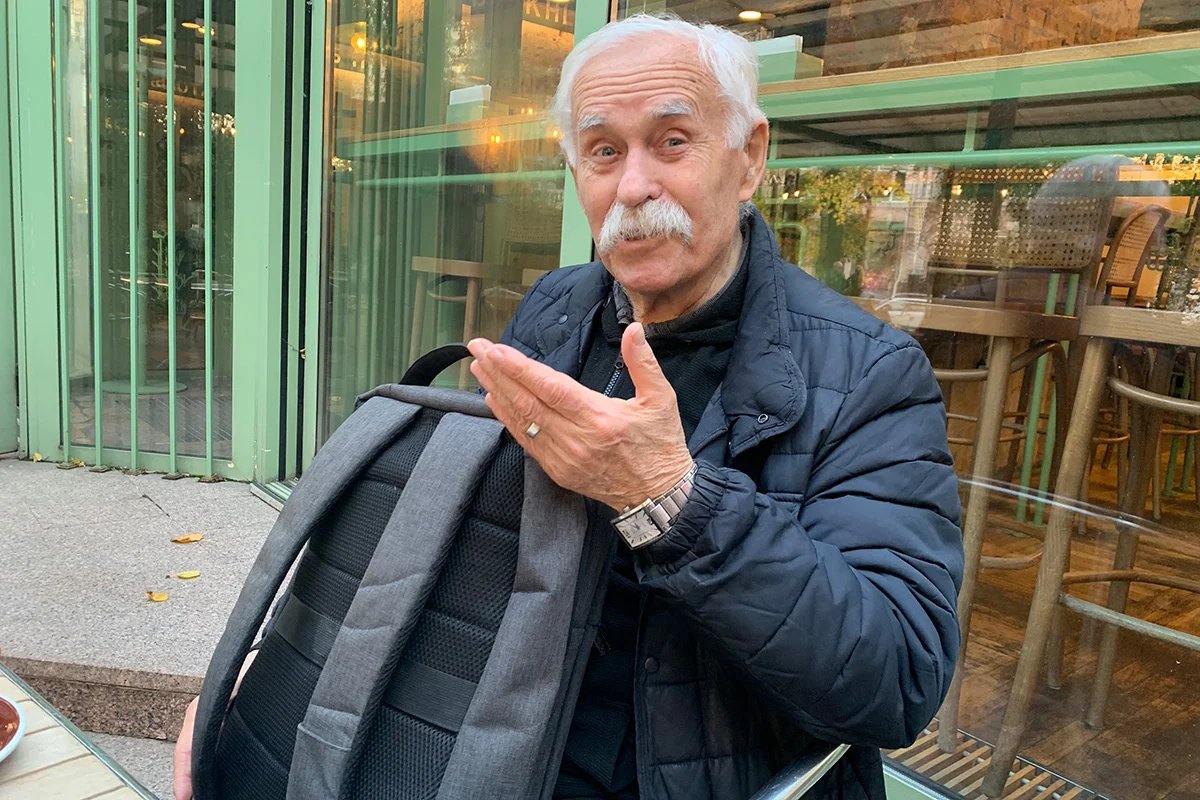

Mykola Malukha is currently the communications director of the Centre for Social and Economic Research (CASE Ukraine), which has already outlined a plan for the country’s post-war reconstruction.

Mykola ends our conversation by saying that “there are still people of Ukrainian origin in Russia, but there is no diaspora”.

Valery, Moscow

Valery Semenenko (top row, centre, grey shirt) at the Ukrainian World Coordination Council surrounded by members of the Ukrainian community in Russia, 2019. Photo from the personal archive of Valery Semenenko

Valery Semenenko is 83 years old. Originally from the Ukraine’s Mykolaiv region, he graduated as a rocket technician, started his career at the Yuzhmash aerospace plant in Dnipro, and then went to work in the gas industry. He was involved in many of the now-banned Ukrainian diaspora structures including the Ukrainian cultural association Slavutych and the Ukrainians of Moscow association. He has also been a member of the board of directors of the Ukrainian World Congress.

When I called Valery, he was in Yerevan with his daughter’s family, having left Russia after the police had searched his home as part of the “fight against extremism“.

This is not the first time he has had to leave the country.

When the Russian authorities were working to shut down the Ukrainian Library in Moscow in 2015-2018, Semenenko had to leave Russia for a few years. I ask him why he risked returning if he knew the direction in which things were going — though I already know the answer. In the absence of Ukrainian diplomats or any other officials able to offer support to war refugees, the 83-year-old Semenenko and a group of enthusiasts (chiefly close relatives) undertook this mission themselves.

“For instance, if volunteers inform us that a number of people have escaped from Luhansk and are currently in Belgorod. We have a small fund that covers the rental of a minibus and petrol and a dozen drivers of advanced age — the old guard… The young ones have left to avoid being drafted. Their task is to transport the refugees towards their destination — Poland or the Baltic states.”

Semenenko and his colleagues have helped countless families return to Ukraine safely. One family from Mariupol — an 85-year-old woman, her 67-year-old daughter and 30-year-old granddaughter, and a cat — ended up at a temporary refugee centre in Ryazan, completely disoriented and exhausted. Semenenko took them to his house to rest and recover and then helped them travel to Germany, from where they still write to him with enormous gratitude.

Larisa, Petrozavodsk

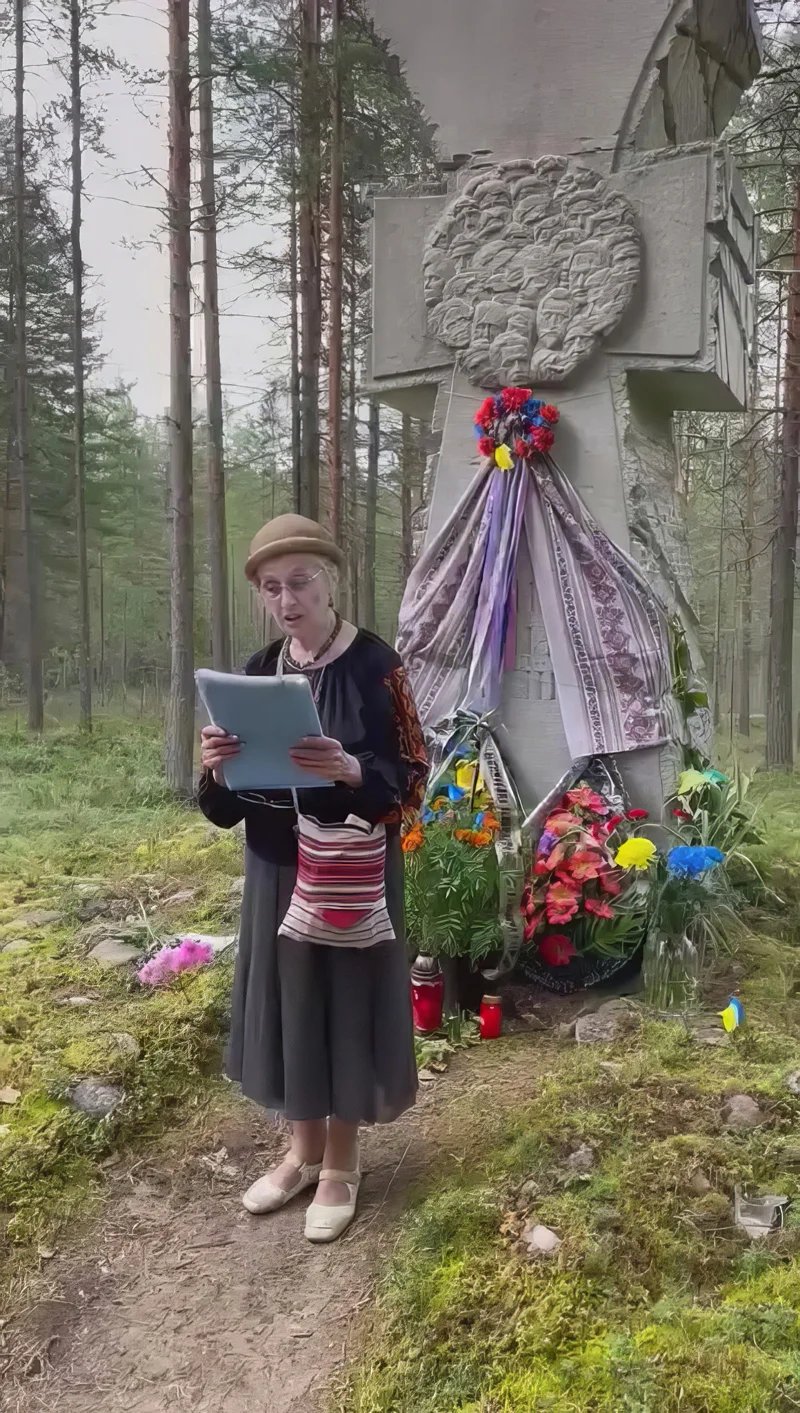

Kyiv-born Larisa Skrypnikova, 82, is the honorary chairman of Kalina, a Ukrainian cultural association in the Republic of Karelia.

In 2004, she played a key role in getting a monument commemorating the Ukrainians killed during Stalin’s Great Terror erected in the northern Russian region. Its stone cross bears the Ukrainian inscription “To the murdered sons of Ukraine” and continues to stand today in Karelia’s Sandarmokh memorial cemetery, where thousands of people from some 58 different nationalities were executed and buried by state security in 236 communal pits between 1937 and 1938.

Larisa Skrypnikova at Karelia’s Sandarmokh memorial cemetery. Photo from the personal archive of Larisa Skrypnikova

Larisa wrote a book about her efforts to get the monument built, which included a foreword by then Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko. A year after it was published, Larisa travelled to Kyiv and presented a copy to the library of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, one of Ukraine’s most prestigious academic research institutes.

Just outside Kyiv is the Bykivnia Forest, Ukraine’s largest mass grave where the victims of Stalin’s mass political repressions of 1937-1941 are buried. The Soviet authorities never admitted their involvement in crime, blaming their own atrocities on the Nazis. It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that the Ukrainian government confirmed the truth about the massacre, and another decade until the forest became a state historical-memorial complex.

Skrypnikova is no longer involved in organisational matters related to the Ukrainian diaspora. She now only concerns herself with what is most important to her, continuing to visit the cross in Sandarmokh each year on 5 August when those murdered here are remembered. It has been 25 years since she attended the first such event, and she went again this year.

Nowadays, only the truly committed continue to gather here each August, and the circle is gradually getting smaller and smaller. Historian Yury Dmitriev, whose tireless research efforts brought Karelia’s “killing fields” to light, is currently in prison on trumped-up charges. Many of Skrypnikova’s fellow activists have also passed away.

But Skrypnikova continues keeping the memory of the Ukrainians killed here alive.

“Neither time nor circumstance can take away everything that we have experienced, organised, and celebrated together. We are sincerely grateful for your perseverance,” reads one message to Larisa from a correspondent in Ukraine.

‘Good’ and ‘bad’ Ukrainians

Volodymyr Kryzhanivsky, Ukraine’s first ambassador to Russia. Photo: Olga Musafirova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

“In Russia, the assimilation of Ukrainians has won over,” says Volodymyr Kryzhanivsky, who served as Ukraine’s first ambassador to Russia from 1992 to 1994.

During our conversation, he asks me to be extremely careful when communicating with ethnic Ukrainians who remain in Russia to avoid getting them into trouble:

“How can there be any talk about a diaspora, especially after 2014? I pity ordinary people in Russia who have Ukrainian surnames. It sounds ridiculous, but nothing that’s happening now makes any sense.”

Ukrainian assimilation has been driven by the image of Ukrainians being traitors that has been honed by Russian propaganda. That same propaganda inculcates the idea that the only “good” Ukrainians are those who consider themselves to be part of one Russian nation.

So having a recognisably Ukrainian surname does not necessarily mean you’ll face discrimination in Russia. In fact many senior Russian military officers are of Ukrainian origin, and many more serve in the lower ranks as well.

There have been countless stories in the media about Russian soldiers who thought nothing of killing Ukrainians and who turned out to have Ukrainian roots themselves, perhaps having lived or studied there, and still having families in the country.

There are even those with Ukrainian surnames in Vladimir Putin’s inner circle: for example, his aide Andrey Fursenko or the oligarch Yury Kovalchuk, who is known for being Putin’s cashier and for being one of the ideological masterminds behind the invasion of Ukraine.

These are examples of what are deemed “good” Ukrainians, with “bad” Ukrainians being those that reject “the collective history” of the two countries and deepen the divide. The Kremlin has a zero tolerance policy towards them, as a string of assassinations of Ukrainian cultural figures over the past two decades shows.

In 2002, Volodymyr Poburinniy, a businessman, philanthropist, and member of the Ukrainian cultural society Mriya, was murdered in Russia’s Ivanovo region. In 2004, Anatoliy Kril, a doctor and head of the Ukrainian choir Gorlitsya, was killed in Vladivostok.

In July 2006, Natalia Kovalyova, the head of the Ukrainian community in the Russian city of Tula was savagely beaten to death by assailants who smashed in her skull and knocked out her teeth with a metal bar.

Months later, Natalia’s husband Volodymyr Kovalyov, another active member of the local Ukrainian community was also murdered. And the list goes on.

Ihor Solovey’s office. Photo: Olga Musafirova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

The head of the Ukrainian Centre for Strategic Communications and Information Security Ihor Solovey, who before the war published into attempts by the Russian state to silence so-called “bad” Ukrainians in Russia, lays out the situation for ethnic Ukrainians in Russia today in uncompromising stark terms.

“Modern-day Ukraine cannot do anything to help Ukrainians who remain in Russia willingly,” he says. “It’s also difficult to help people in the occupied territories, but at least there is some hope there.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]