The day after Russia invaded Ukraine, a group of Russian feminists banded together to found the Feminist Anti-War Resistance (FAS) online. The organisation quickly gained worldwide media attention, with its Telegram channel gaining more than 26,000 followers in its first month. Its most successful action, Women in Black, brought “thousands of women around the world” to the streets every Friday, FAS co-founder Lelya Nordik said in a 2022 interview with Radio Liberty. The women dressed all in black — and sometimes carried white roses — to memorialise Ukrainian victims and demonstrate their opposition to the war.

Daria Serenko, another founder of the FAS, told Novaya Europe that the action had been devised to prompt dialogue. The idea was first used by female activists in Israel in the 1980s who staged Women in Black demonstrations to protest the occupation of Palestine.

Almost as successful was another FAS action entitled Mariupol 5000, in which people across Russia erected homemade crosses for the victims of the siege. FAS members have also been leading support groups for women, publishing Ukrainian testimonies about life under Russian occupation, and teaching refugee women how to recognise the warning signs of human trafficking and where they can go for help.

Ella Rossman, an FAS organiser and PhD candidate at University College London, said that the group had intentionally cut back on street actions in the interest of member safety, citing the case of Sasha Skochilenko, who on Thursday was given a seven-year prison sentence for placing price stickers with anti-war messaging in her local grocery store. FAS is now focusing its energies on online initiatives such as these, as well as investigative journalism and anti-disinformation projects.

Nordik agreed that one of the organisation’s main purposes is to counter the “information blockade.” Members have written and disseminated anti-war texts in various formats, including several modelled on Orthodox prayers — called “Prayers to the Mother of God” — that went viral in March last year. FAS members including coordinator Liliya Vezhevatova have also started a newspaper called Women’s Truth, published in the style of an old-fashioned regional newspaper and targeted at older women in Russia. It integrates stories about female anti-war activists, especially older ones, with anti-war jokes and other useful information, such as how to install a VPN.

As for the younger generation, Serenko said FAS regularly publishes a pamphlet called Anti-Lessons, which is targeted at teenagers and aims to counteract the propaganda they receive in their mandatory “Important Conversation” civics classes at school. Other Russian feminists, including Leda Garina and Yalia Karpukhina, have spearheaded educational video series for young people in which they discuss Russian imperial exploits, delivering what the channel’s main page calls a “feminist criticism of imperial myths”.

Garina and Karpukhina previously ran a feminist hub called The Rib of Eve in St. Petersburg but have now relocated to the Georgian capital Tbilisi, they told independent Russian media outlet Bumaga in June. Their channel has 22,000 followers, and its videos include a series called An Army of Rapists and a video called Feminists vs Prigozhin.

Garina and Karpukhina admitted that “even for a feminist audience, the connection between violence toward women and military violence [is] not always obvious.” However, they said, for them the two movements are intrinsically connected.

Without the patriarchal “myth of the warrior,” Garina said, in which a man is fundamentally a “defender,” it would have been much harder for the Russian authorities to rally support for its invasion of Ukraine.

Garina and Karpukhina are far from the only Russian feminists to have fled the country. Many activists associated with the FAS who have remained in Russia have, like Skochilenko, been arrested for their actions. Still, political action among Russian women is on the rise: a poll by prisoners’ rights non-profit OVD-Info showed that the percentage of women detained in protests had increased dramatically in the last two years — from 25% to 44% of detained people.

The actions of the FAS and the imprisonment of some of its activists seem to tell a familiar story about feminism in Russia — one in which Russian feminism and activism are aligned, and both are opposed to the Putin regime.

However, another emergent strain of feminism in Russia is increasingly pro-Putin and pro-war. For a long time, the FAS manifesto explains, “the Russian authorities did not perceive [feminists] as a dangerous political movement”, and Putin himself has occasionally seemed to co-opt feminist rhetoric for his own purposes, stating in public appearances that there is nothing wrong with feminism and even calling protecting women’s rights steps in the “right direction”.

Maria Arabatova. Photo: Facebook

The country’s ruling party, United Russia, launched an initiative in 2022 called the Women’s Movement, which aims, according to their website, to help women in their “long struggle for equality.” Most recently, the state’s efforts to drive up women’s enlistment in the army have appropriated the girlboss language of feminism: a recent recruitment campaign, for example, reminded women that they were “not only made for cooking soup and having children”.

On the most radical end of this pro-war feminism are a handful of online forums, video series, and famous cultural figures. Writer and feminist Maria Arbatova tops this list: Arbatova became a household name in the 1980s and 90s for her feminist writing, including a play about abortion and an essay collection called “My Name is Woman,” but she has since become better known for her radical nationalism.

After vocally supporting the annexation of Crimea and attending anti-migrant protests organised by the Russian government, Arbatova asserted in an interview last April that Ukraine was “not a fully-fledged state” and defended the Russian mission against “UkroNazis” who were “killing pregnant women.” She declined to respond to Novaya Europe’s questions about her pro-war feminism because, she said, the organisation was “dubious.”

Z girlfriends. Photo: YouTube screenshot

Several online video series, forums, and pages broadcast a similar brand of nationalist feminism. In May, journalists Anastasia Kashvarova and Yekaterina Agranovich came out with two episodes of a TV show which they called Z girlfriends, adding the pro-war Z symbol to the title of a very popular Russian feminist TV show called Girlfriends. In the Women at war episode, which 75,000 people have watched on YouTube, three “pretty and young women discuss the new realities of life in Russia.” More specifically, the topics of discussion include the difference between Russian and Ukrainian concepts of femininity, the way in which war “enlivens” people, and the need for pro-war women to “reveal their femininity” since Joan of Arc “also attracted men by her appearance.”

Two other examples of feminist-nationalism online are the VK page FACTS_ANTIsexism_ANTIchauvinism and the Women’s History Group, both of which were formed in 2012 and boast around 20,000 followers. Both groups have become more and more explicitly pro-Putin since the war began. In February and March of 2022, FACTS still appeared relatively moderate, urging people to beware of misinformation “on both sides” while also claiming that “suffering in the Donbas” had gone ignored for years. Now the page is far more extremist, with some posts criticising “Western liberal neo-fascism” and others calling the members of the FAS “Russophobic terrorists” and “Soros fangirls”.

The Women’s History group espouses similar views, praising the “heroines of the special military operation in Ukraine” and swiftly quashing dissenters — which it calls “Ukrainian bots” and “Nazi sympathisers” — in the comments section. Alongside these posts, both the FACTS and the Women’s History page continue to publish benign feminist content including news about women’s protests around the world.

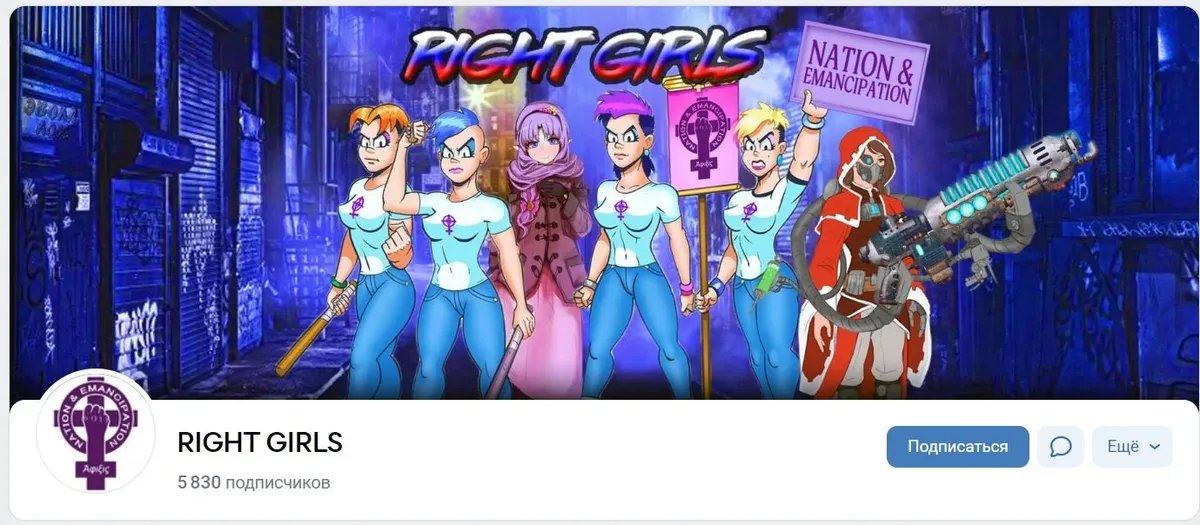

An even more radical online community is Right Girls, a VK page with almost 6,000 followers which advertises itself overtly as a forum for “feminist nationalists”. Since its creation in 2014, the page has become a deep repository of xenophobia, Islamophobia, and other far-right talking points, alongside more standard feminist posts decrying sexism, rape, and restricted access to abortion.

Photo: VK

Both Rossman and Katya, an FAS representative whose name has been changed for her safety, made the point that Russian nationalist-feminism is not exclusively a product of the war. Even before the invasion, they said, pro-government feminist bloggers such as Anna Federova were trying to create a “pro-Putin feminism” that would paint the Russian president as a defender of women.

In Rossman’s view, Putin supporters’ apparent interest in feminist rhetoric shows that they realise they need to increase their popularity among younger Russians. Many polls have shown that Putin’s base is primarily middle aged: the appeal to the feminist agenda, Rossman believes, is an attempt to “target younger audiences that they can’t reach.”

Rossman and Katya both said they consider the far-right position of groups like Right Girls — and individuals like Arbatova and Federova — “fairly marginal”. These groups lie, Katya said, on the far end of a “spectrum” of pro-war feminisms in Russia. Rossman agrees: extreme pro-war feminists like Arbatova, she said, “aren’t very popular or dangerous.”

The more pernicious kind of pro-war feminist, Rossman said, is the feminist who claims to oppose the war while still repeating propagandistic rhetoric — saying, for instance, that the situation is “very complicated” and the Ukrainian government “isn’t perfect either”.

These feminists “say that they are anti-war, but in reality they are employing propaganda tropes and disseminating them,” Rossman said. “This is very problematic.”

Just as there are many kinds of feminism in Russia, Rossman said there are many levels of propaganda. “Not all propagandists are trying to convince you to support the war,” she said. “Some of them just want you to be unsure.”