Georgy Urushadze’s Freedom Letters publishes books that would never get past the unofficial censorship of more mainstream Russian publishers. Despite opening just six months ago, it has already established itself as both a key player in the Russian literary world and a formidable enemy of state propaganda.

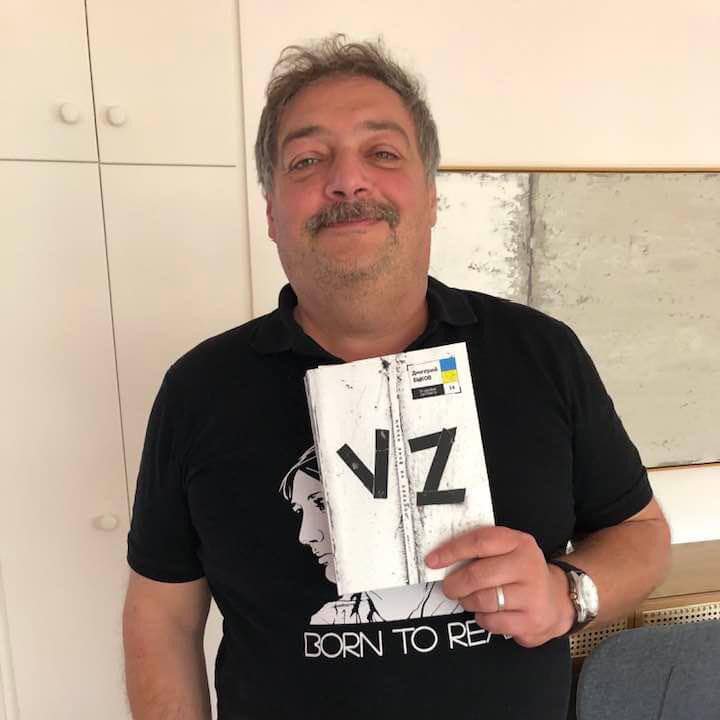

So far, its publications include Sergey Davydov’s groundbreaking queer novel “Springfield”, numerous books in Ukrainian, and Dmitry Bykov’s portrait of Volodymyr Zelensky, entitled “VZ”, which plays off the fact that V and Z are both prominent pro-war symbols in Russia.

Founder Georgy Urushadze has long been an important figure in the Russian literary scene, working as a journalist in the 1990s before going on to become an editor at Palmira, where he published writers including future Nobel literature laureate Svetlana Alexievich and best-selling author Alexey Ivanov. Until last year, Urushadze was the director of Russia’s premier literary prize, Bolshaya Kniga (Big Book), a post he resigned from following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

School of Russian Language and Culture at RKPOM. Photo from Facebook

NGE: How did Freedom Letters come into being? Is it true that you opened it in literally two weeks?

I had been thinking about starting a publishing house all last year, but I couldn’t find a viable business model. Publishing books in the current circumstances — when there’s no distribution allowed within Russia, but most of our readers live there — is totally unprofitable. For every dollar you make you’ll lose 20. So it’s crucial to have sponsors and volunteers. We don’t have any sponsors yet, but we do have more than 40 volunteers — and it’s thanks to them that the house has developed so rapidly.

In March 2023, I called Vladimir Kharitonov, who is now the technical director of Freedom Letters, and said: “Let’s put out 10 books by 17 April.” He said that I was crazy, that it was impossible, and that we’d need way more time to get the books ready. But I’d been champing at the bit for six months already. I said, if we don’t do it now, we never will. I convinced him — and myself — that we could do it, though then of course we had to work nonstop for several weeks. On 4 April, I publicly announced that the publishing house would open in two weeks. Exactly 14 days later, we brought out our first 10 titles.

Dmitry Bykov. Photo courtesy of Georgy Urushadze, from Facebook

NGE: Tell us how the publishing house works from the inside. Its operations and employees are scattered across the globe, right? How do you coordinate the various processes?

GU: Our processes have become so streamlined that we can in theory turn a manuscript into a published book in 10 days — especially when there’s a sense of urgency in its subject matter. It was that fast, for example, with Andrei Krasnyashchikh’s book “God Exists +/-”, which was written during the bombing of Kharkiv. I accepted the manuscript immediately without changing a word and sent it off to be proofread. It came out immediately in both print and electronic versions and is now available all over the world. Sergey Davydov’s “Springfield” and Vanya Chekalov’s “Love” were published in similar timeframes, just a few weeks for each, with minimal editing.

Sergey Davydov. Photo courtesy of Georgy Urushadze from Facebook

NGE: How does the house pay for itself? Volunteers of course work for free, but where do employee salaries come from?

GU: Volunteers are a very important part of our process — and not just because we save money with them. It’s more about the collective energy volunteering creates. When people are willingly investing so much of their energy, time, thought and emotion into pursuing a shared goal, the effect is far greater than when employees work just to earn money.

I pay for whatever we need with my own money. Our costs are pretty low now, but we are applying for support grants. We haven’t paid for any of our books and not a single one of our editors would accept money either — it’s all down to the goodwill of the volunteers. The authors receive royalties. Everyone else works for free, including me. I’m a volunteer at my own publishing house.

Any work in publishing these days is quite thankless. To make a profit you have to publish a real hit or two, and then live on the money from those.

I believe that you can’t only publish bestsellers. There are piles of books that demand publication — that scream to be published.

NGE: Does Freedom Letters have an editorial policy? Who makes the final decision?

GU: That person would be me. It’s a heavy burden, actually. I try to be very sensitive and courteous when dealing with authors; I hate to reject them, but I have to. We don’t have censors, so we don’t have, for example, an editor-in-chief responsible for upholding an “editorial policy”. If a book aligns with our general ethos and if, in my view, it’s well-written, it will be published. I make no claims to know whether a book is “good” in the universal sense, but within the framework of my publishing house I have to decide … In addition to looking for good, powerful writing, I also think about why a book should be published by us. For example, I rejected one very good book and advised the author to try Russian publishers, as it wasn’t the kind of book that only Freedom Letters could publish. Basically, if a book can’t be published in Russia, then we’ll seriously consider it. If it could be published in Russia, it’s not clear why we should publish it.

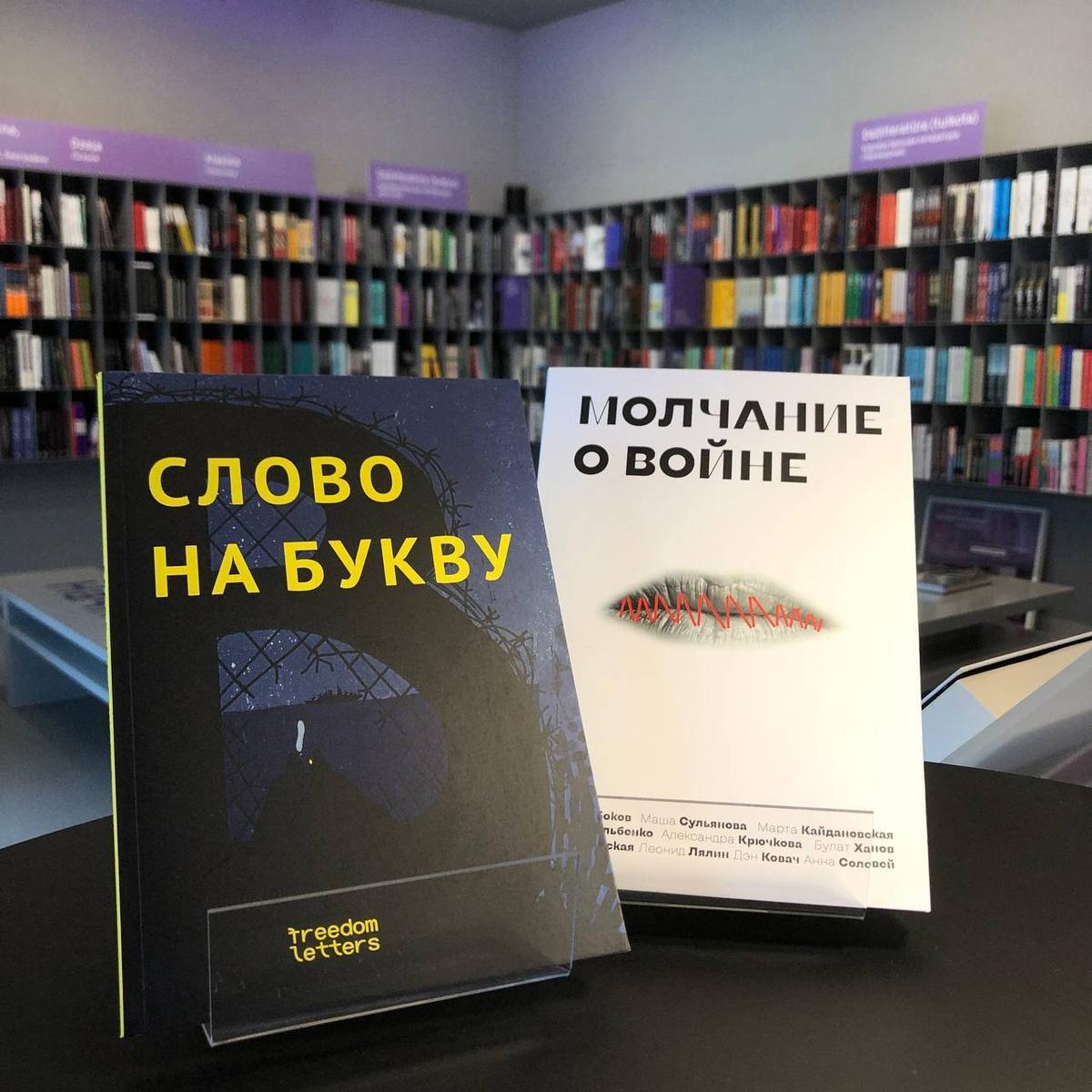

Books in Riga. Photo from the Freedom Letters Telegram channel.

NGE: The publishing house has been in operation for six months. How would you describe what you’ve managed to achieve in that time?

GU: At first, my goal was to publish 30 ebooks by the end of 2023 and publish our first paper book sometime this autumn. But everything has come together much faster than I anticipated. We’ve already published 45 ebooks and about 40 paper books; there are another 45 ebooks and 45 paper books in the works. We’re starting to work on some audiobooks too. Our goal is not just to find good books and publish them beautifully, but also to make them available to every reader, no matter where they live. You might be wondering about our readers in Russia — we haven’t forgotten about them — our ebooks are available through a bot named letterspay_bot on Telegram.

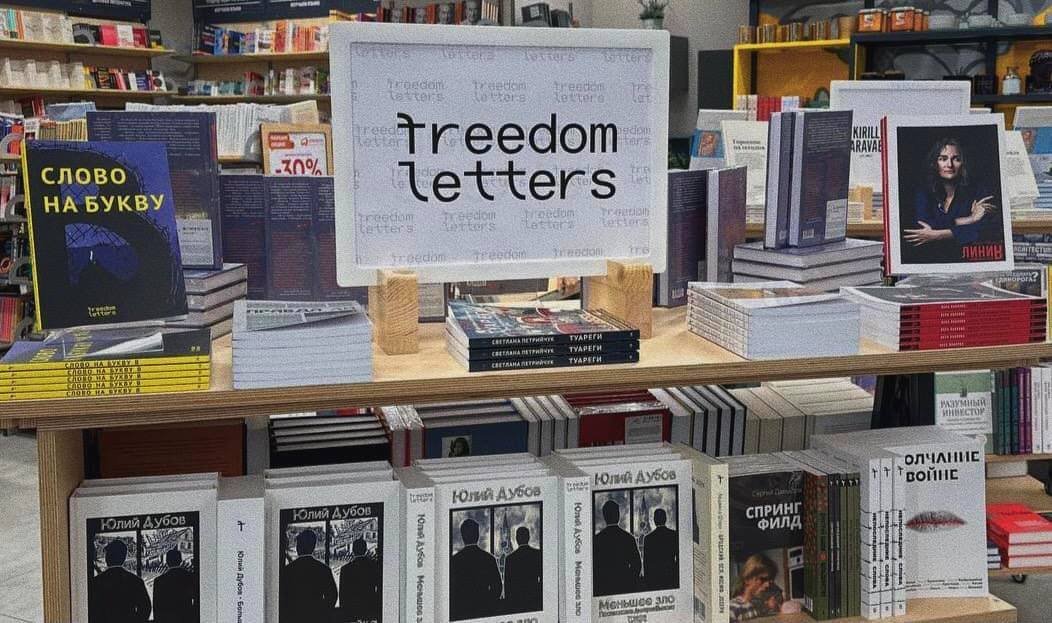

A shelf of Freedom Letters titles in Kazakhstan. Photo from the Freedom Letters Telegram channel.

NGE: The first of the 10 books you published was the flagship queer novel “Springfield”. Why did you choose that?

GU: Yes, I came up with the gimmick of giving each of our books a number. And I gave “Springfield” the number one intentionally. This book is one of our messages. I really think that while short, it’s a magnificent, serious, and important novel — extremely well-written, both from a literary and a psychological point of view. For me personally, the topic of human rights, no matter how it’s expressed, is extremely important. After hearing that we’d published “Springfield”, tons of authors began to send us queer and even pornographic novels, but most of them haven’t passed muster. “Springfield” set the bar very high: the books have to be literature.

That first batch included some titles that provoked anger in Russia: a collection of poems by the Ukrainian poet Alexander Kabanov called “Son of a Snowman,” and Yevgeny Klyuev’s “I am From Russia, Forgive Me”, which is actually a very gentle book, but the Z-maniacs were livid about the title. We also published Vitaly Pukhanov’s collection “The Motherland Will Order You to Eat Shit.” I wanted to show our rebellious side with that title: not many publishers would put that word on the cover of a book.

NGE: What do you think literary demand will look like in Russia after the war?

GU: The trauma we’ve all suffered — and continue to suffer — from this war is enormous. And working through it will take decades. In my view, one of my most important tasks is to help Russian speakers overcome imperialist and belligerent ways of thinking. So I published a children’s book, “The Word That Starts With W”, and I want to publish more. We’re also working on a series of classics by great writers with new forewords. The idea is that these forewords will provide anti-war, anti-totalitarian lenses through which readers can view these great works. Another of our recent books was called “The Fascists Have Little Paint,” which was about grassroots resistance in Russia — how people wrote “No to War” on autumn leaves and scattered them in parks, for example. There is a way out, I believe, and the future may not be entirely bleak — but, again, only for people who are committed to that brighter future, not for everyone.

I don’t know how the war will end; it’s impossible to predict the future. But just as there will always be unpleasant people living anywhere, there will also be decent people wanting to read decent books. Everyone has already chosen which side they’re on. The Z-patriots seem to be well aware of their lack of decency. There is no real patriotism there — they are, of course, Russia’s real enemies. They don’t even believe what they are saying themselves.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]