The Russian-Ukrainian war has reached a stalemate. Neither warring party can gain a decisive advantage and inflict on the enemy the kind of damage that will force them to make significant and principled concessions. The Ukrainian advance is moving ahead too slowly or has even bogged down completely, therefore, Moscow and Kyiv should declare a ceasefire and launch talks to work out a model that would settle the conflict. These headlines and alike have flooded global news agencies and media outlets and are seen by many as the absolute truth. But here’s a question: do these claims actually describe what’s happening right now on the frontlines? At Novaya-Europe’s request, military expert Yury Fedorov analyses key narratives of the current stage in the Ukraine war.

Support independent journalism

All independent media have been banned in Russia which makes our work not only challenging but outright dangerous. We need your support.

Positional stalemate?

The current state of affairs on the frontlines in Ukraine is somewhat reminiscent of World War I, the situation which is sometimes called “positional stalemate”. The warring parties were prepping for rapid and swift advances in 1914. However, machine guns and trench artillery that made their way to regular armies gave the defending side much greater advantages to hold on in the face of an attack. The attackers resorted to using large-scale artillery strikes to suppress enemy defences, while the defenders constructed a deep-echelon system of trenches and fortifications that could not be overcome easily and resulted in huge losses. As a result, the frontline stabilised.

However, the situation had changed by the time the Second World War began. New and powerful means of breaking through defence lines — attack armoured tank units and frontline aviation — prevented another “positional stalemate”. That war turned into a manoeuvering one, with dissecting strikes, enemy encirclement operations, tank battles, and swift sallies into the enemy’s rear becoming the basis of the combat.

The full-scale war between Russia and Ukraine represents a blend between these two wars. The conflict was characterised as a manoeuvring one, albeit with certain reservations, up until the late autumn of 2022.

Combat aviation was not playing a major role in it. Ukraine has few jets, while Russia is scared of using them for fear of losing aircraft to Ukraine’s effective air defences. Armoured vehicles and artillery were the main tools of the war. During the “Battle for Donbas”, the Russian army was assaulting cities and towns head on in the spring-summer of 2022, using the barrage fire tactic. Up to several tens of thousands of artillery shells were expended per day, which flattened city quarters and Ukrainian defence strongholds located there.

However, the occupation of Lysychansk in early July 2022 showed that Russia’s advance potential had almost exhausted itself due to huge personnel and weapon losses.

The Ukrainian army, in turn, carried out two successful offensives that de-occupied the Kharkiv region and chased Russian troops away from the right bank of the Kherson region. The Ukrainian advance had stalled by the time winter came, mainly due to deployment of draftees in the Russian ranks and several tens of thousands of Wagner Group fighters recruited mostly in prisons.

The 72nd brigade soldiers reloading a T-64 tank on the Vuhledar axis, Donetsk region, Ukraine, 19 July 2023. Photo: Jose Colon / Getty Images

In late January 2023, Russia launched the “second Battle for Donbas”, throwing large groups of forces at the enemy across the east frontline, targeting Marinka, Avdiivka, and Kupiansk. The only result? The capture of Bakhmut after four months of bloody clashes, where Wagner forces played a key part. The frontline barely moved anywhere else.

In turn, Kyiv announced preparations for a counter-offensive in summer 2023, which was expected to land a decisive victory for the country. Thanks to Western allies’ help, Kyiv assembled a rather powerful group of forces to carry out the operation. Moscow seemingly did not have much hope for its troops holding up under the attack and responded by creating a system of engineering fortifications adorned with several-kilometre wide minefields in the Zaporizhzhia region as well as an offensive on the section of the eastern frontline from Kreminna to Svatove.

Generally, the situation right now truly resembles a positional stalemate:

Ukraine is trying to advance in the Zaporizhzhia region and near Bakhmut but the progress is slow; Russia is attempting to break through to Lyman and Kupiansk but to no avail.

The question is as follows, however: is it a stalemate or a dynamic equilibrium that can swing either way later?

Number of troops, strategies, and tactics of the parties

The answer largely lies with how the two forces stack up against each other and what the parties do. According to Ukraine’s data, there are up to 370,000 Russian soldiers and officers stationed on Ukraine’s occupied territories, including 47 brigades (180,000-190,000 service members) that are intended to take part in combat operations, while the rest ensure timely provisions and logistics. These forces are deployed along the 1,000-km long frontline, from the Dnipro mouth in the Kherson region to the small village of Dvorichne in the Kharkiv region. The largest group of Russian forces — around 100,000 people, 900 tanks (almost half of all Russian tanks), and more than 550 units of artillery — is concentrated on the northern part of the eastern frontline between Kreminna and Dvorichne.

This group of troops has two key tasks to accomplish:

- Firstly, to force Ukraine to redeploy to this section its reserve forces that are primarily earmarked for the Zaporizhzhia region offensive.

- Secondly, if they successfully reach Kupiansk and Lyman, to turn south towards Sloviansk and then to Kramatorsk, ultimately reaching the main strategic goal set by Putin a year ago: occupying the whole territory of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

Russian forces use the same tactic they applied during the first Battle for Donbas: a relatively large group of least-trained infantry marches forward in the first line of offensive forces with artillery support, followed by armoured vehicles and then elite assault units.

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Ukrainian army had almost 690,000 people in the beginning of 2023, including 250,000 in land forces, 30,000 in airborne units, and around 350,000 in the territorial defence troops (see Military Balance, 2023. IISS. 2023. P. 201. — editorial note). All these service members are not stationed along the frontlines: Ukraine is forced to deploy significant contingents in the north, along the Ukraine-Belarus border, in the east, and in the centre of the country as strategic reserves.

The Ukrainian Armed Forces have significantly fewer combat jets than Russia, who also has an advantage, albeit dwindling, in artillery and armoured vehicles.

So, here’s a question: can Ukraine hope for a successful offensive? All military manuals rightfully state that the attacking party forces should have a two-three time advantage over the defending one. However, these very manuals have quite a few examples when the dominating side loses to the enemy that had fewer forces at its disposal. Indeed, the numbers alone do not tell the whole picture, the factors that predetermine victory or defeat include commander skills, troop morale, timely communications, ability to redeploy troops to decisive sections of the frontline, and so on.

Ukrainian soldiers in battle positions ready to fire BM-21 towards Donetsk, Ukraine, 20 July 2023. Photo: Diego Herrera Carcedo / Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

Western media outlets, citing classified Pentagon documents, are reporting that Kyiv in the spring of 2023 was readying 12 mechanised brigades, nine of which were equipped and trained by Western allies, as well as eight assault brigades of the National Guard for its planned offensive. Taking into account that the standard number of troops in a mechanised brigade stands at 3,500-4,000 soldiers and officers and the fact that they have specific weapons and vehicles, the Ukrainian command was training around 70,000-80,000 personnel and 500-600 tanks or infantry fighting vehicles, half of which or even more were supplied by the West.

Mark Milley, US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, recently noted that the West had trained 63,000 Ukrainian soldiers and officers that formed 17 brigades, most of which fall within the “significant” reserves of the Ukrainian forces who are expecting orders to go into fighting at the time and place determined by Kyiv. Therefore, if the Ukrainian army deploys its attack group of forces on a thin stretch of the frontline, they can hypothetically break through the defences and reach the Russian rear.

Ukraine is currently on the offensive in the Zaporizhzhia region, using small and manoeuvring groups equipped with armoured vehicles to push Russian troops out. Ukrainian military engineers are simultaneously clearing passages through minefields. It is clear that Kyiv has achieved tangible results, but they have been unable to break through the well-fortified Russian defences. However, it’s worth mentioning that it’s not their primary goal. The idea is to keep enemy forces stretched across the frontline. The decisive turn of events will come when Ukraine sends its trained group of forces to battle.

Ukraine’s offensive will truly begin when the military command and President Zelensky conclude that success chances significantly outweigh the defeat potential.

There is some ground to believe that this is exactly what will happen. For instance, in the course of the counter-offensive, Ukrainian troops are seemingly winning counter-battery engagements, which often determine who will be victorious. For each destroyed Ukrainian artillery gun, there are four Russian ones.

Since the start of the Kyiv offensive, Russia has lost more arms and military vehicles than Ukraine in a month. Oryx, an analytical centre that tracks war developments based on satellite images of battlefields, has confirmed that Russia lost 433 units, while 322 pieces of Ukrainian military equipment were destroyed in the same period.

Keeping in mind that Russia has many-fold advantage in this category, this loss ratio confirms that Ukraine outperforms Russia in the quality and skillfulness of command, the morale department, and other factors that go beyond the mere numbers.

Possible scenarios

The current state of dynamic equilibrium can be disrupted in two cases:

The first scenario is Ukraine manages to break through the Russian defences in the Zaporizhzhia region and reach the Russian rear on one of the three main axes: Mariupol, Berdyansk, or Melitopol. The Ukrainian breakthrough has the potential to topple the whole Russian frontline. A small Ukrainian advance by 20-30 km can paralyse railway traffic in the Zaporizhzhia region that plays a vital role in Russia’s logistics across Ukraine’s occupied southern territories. If this development coincides with a destruction of the Crimean Bridge railroad, Russia’s defeat in southern Ukraine will become much more tangible.

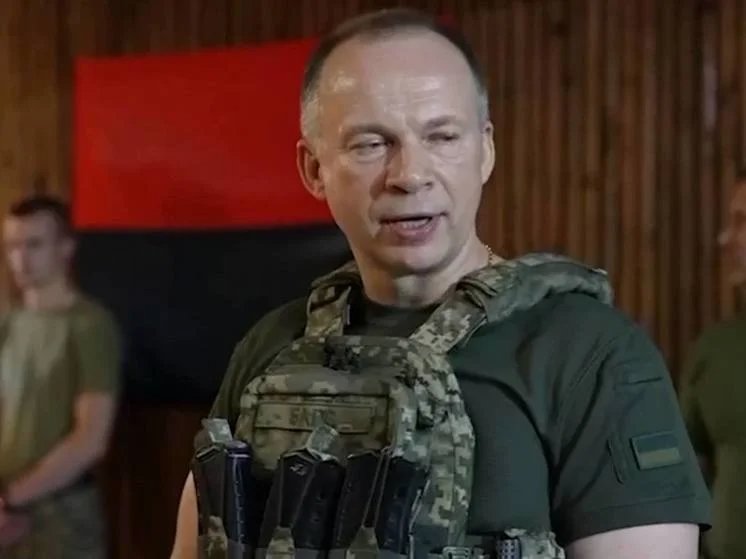

Oleksandr Syrskyi. Photo: video screenshot

Another scenario is the plan by Commander of Ukrainian Ground Forces Oleksandr Syrskyi aimed at encircling Bakhmut tactically. If it is successfully implemented, Russian troops will be forced to withdraw from the city, while the Ukrainian army can potentially ride this wave of success to march further into the Donetsk region, where Russia does not have such a sophisticated system of fortifications and minefields like in the Zaporizhzhia region. In other words, Ukraine’s main blow can come in the Donetsk region as well.

On the other hand, a hypothetically successful Russian advance on Kupiansk or Lyman can also be consequential. However, even military forecasts picture them as much less formidable. If it does happen, the main strategic goal of fully occupying the Donetsk and Luhansk region will see the Russian army engaged in drawn-out and low-prospect assaults of Sloviansk, Kramatorsk, and Seversk, along with other well-fortified Ukrainian cities.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]