Sergey Shoigu entered one of the most horrendous times in Russia’s modern history — the war against Ukraine — as the defence minister. He stepped into the political limelight during the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis, also known as the October coup, but is nearing the end of his tenure following the recent failed coup attempt in 2023.

Novaya Gazeta Europe recalls the professional pathway of Sergey Shoigu and teams up with experts to figure out what will happen to him now.

Shoigu and Siberia

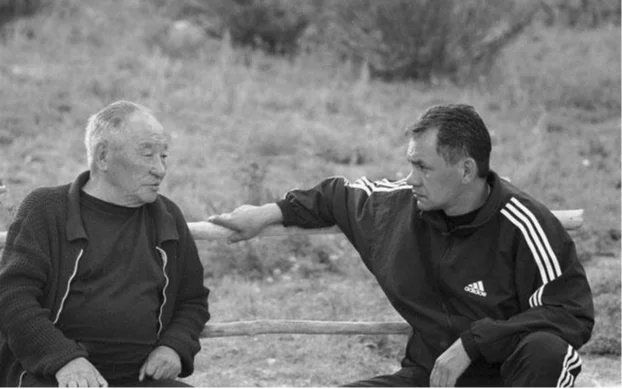

Sergey Shoigu was born on 21 May 1955 in the town of Chadan, Tuva autonomous region. Shoigu spent most of his childhood and adolescence in Siberia. His father, Kuzhuget Shoigu, was the editor-in-chief of the regional Pravda newspaper who went on to build a successful political party career later.

Shoigu’s mother, Alexandra Kudryavtseva, was born in Ukraine but moved to Tuva where she met Kuzhuget. The family had three children, Sergey Shoigu and his two sisters.

Kuzhuget and Sergey Shoigu. Photo: Tuva region government

When Sergey Shoigu was five, he was christened in the town of Stakhanov (currently Kadiivka, Ukraine’s Luhansk region), where his mother’s relatives lived at the time. The minister told this story to reporters three years before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. He was even asked then if the armies of Russia and Ukraine could ever directly face each other on the battlefield.

“I don’t even want to think about it!” he responded, stressing that this turn of events would be “crazy”. He said that his mother’s family was from Ukraine, where they lived under Nazi occupation during WWII.

After graduating from school, Shoigu obtained a diploma as a civil engineer and worked on major Siberian projects for the next ten years until the end of 1980s.

The year of 1990 predetermined the whole future career of Shoigu. The talented engineer and professional was noticed in Moscow and offered the job of the deputy head of the state committee for architecture and construction. Shoigu and his family moved to Moscow.

Sergey Shoigu and Boris Yeltsin in Tuva. Photo: Tuva government

Yeltsin-era Shoigu

In 1991, Sergey Shoigu, 36, received an offer to take the reins in reforming the Russian Rescue Corps — rapid response service — even though he had no experience with working in active combat zones or hotspots.

The service was soon renamed into the Emergencies Ministry. Shoigu and his deputy Yuri Vorobyov staffed the newly formed institution with people who fought in the Soviet-Afghan War, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and the Chechen war.

Shoigu found himself in the midst of an armed conflict in 1992 for the first time, when he was instructed to create peacekeeping forces in South Ossetia.

“War is a dreadful thing. I say this because I know very well what it is,” he recalled later.

The dreadful war, which he would fervently support, was still 30 years away.

Meanwhile, Russia was embroiled in a constitutional crisis of 1993. The decision to assault Moscow’s White House, seat of the government where supporters of the Supreme Soviet barricaded themselves in, was made by President Boris Yeltsin in the early hours of 4 October.

The key issue was what to do if the military refused to follow the presidential instruction and whether backers of the president who gathered near the Moscow City Council building could be used instead. In this case, they would need to be armed. This is the request that Yeltsin’s loyal entourage presented to Shoigu.

Shoigu followed through with the appeal. Witnesses’ accounts state that three cars loaded with 1,500 assault rifles arrived at the site. However, the arms were not necessary — the army fell in line with the president’s order.

Moscow, 4 October 1993. Photo: EPA/ANATOLY ZHDANOV

Shoigu was awarded a Medal to the Defender of a Free Russia and promoted to major general by grateful Yeltsin. Two years later, Shoigu rose to lieutenant general and then colonel general. He then climbed all the way to the army general rank under Putin.

Early Putin-era Shoigu

On 31 December 1999, Yeltsin resigned and handed the reins over to Putin. Between January and May 2000, until Putin’s inauguration, Shoigu was his deputy in the government, simultaneously keeping his Emergencies Ministry office.

Acting Russian President Vladimir Putin and Emergencies Minister Sergey Shoigu vote during the Unity party congress, at the Moscow Kremlin, 27 February 2000. Photo: EPA PHOTO EPA/SERGEY CHIRIKOV

Unity, a new political movement that was spearheaded by Sergey Shoigu and backed by Putin, scored 23.3% of the votes at the elections held before Yeltsin’s decision to step down. The Unity soon merged with several other political forces to form a new party — United Russia.

Shoigu, as a United Russia member, steadily had a high approval rating at later legislative elections. He was considered one of the most popular ministers. By the way, Shoigu holds the record of staying at a ministerial post the longest in the post-Soviet era: he headed the Emergencies Ministry for more than 20 years: from 1991 to 2012.

Defence Minister Shoigu

In November 2012, Shoigu was quickly promoted to defence minister to replace Anatoly Serdyukov, a disgraced politician who was fired over multiple scandals and criminal cases opened against him.

Shoigu’s official biography notes that after assuming the new role, he “significantly improved the intensity of combat training”, conducted numerous unexpected inspections of combat readiness (to find out what’s really going on in the army), reinstated many officers who were previously sacked, increased the number of service academies, established Arctic troops, and built a new academy for the strategic missile forces.

Moreover, Shoigu oversaw the construction of Patriot, the largest military and patriotic park in the country, and the Defence Ministry church that contains frescoes of Stalin, Putin, and Shoigu himself. However, one of the most important brainchildren of the new minister is the Young Army Cadets National Movement, a patriotism-inducing paramilitary movement for kids aged between 8 and 18. All these initiatives were ridiculed online and in Russia’s independent media outlets.

Shoigu was also involved in a number of scandals that unfolded following investigations involving his relatives. The Insider, Open Media, and Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation uncovered many expensive properties and businesses belonging to Shoigu’s family members — from his wife’s sisters to his younger daughter. Reports also emerged about his mistress who had a Lithuanian residence permit and the children they had together while Shoigu was married. The investigations shed light on various schemes, ties, administrative resources, corrupt businesses, state contracts, and bribes. In short, everything that Putin’s elites are known for. Like the rest of them, Shoigu stayed silent about all the accusations and allegations. He only once mentioned that it reminded him of “the mass denunciation campaign in 1937”.

Despite these small troubles, Shoigu seemingly achieved everything he ever dreamt of. A boy from a small town in Tuva was in charge of Red Square parades 50 years later.

There was something wrong with the look on his face though. Shoigu from the Yeltsin era always had a charming smile, while Shoigu under Putin was decorated like a Christmas tree with medals and orders but gained weight and was never seen smiling in public again.

Sergey Shoigu. Photo: Sefa Karacan/Getty Images

Shoigu and Ukraine

The life of a religious minister, who was once baptised in a church in Ukraine, was only marred by criminal prosecution launched by Kyiv. The main investigative department of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry opened a criminal case against Shoigu and Russian businessman Konstantin Malofeev on suspicion of creating illegal paramilitary or armed groups in July 2014, after the MH17 plane crash over Ukraine’s Donbas.

In 2021, the Ukrainian Security Service demanded that Shoigu attend a hearing in Mariupol as a defendant in the same case of “creating illegal armed groups”. Naturally, Shoigu ignored the summons.

Less than a year after that, Mariupol would be reduced to rubble in Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

Russian Security Council meeting, 21 February 2022, Photo: the Russian President’s website

And then 24 February 2022 came, a date that made The Hague trial a possible outcome for the minister in the future as one of the warmongers that oversaw the invasion.

Shoigu attended the Russian Security Council on 21 February, when Putin announced that the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics, Ukraine’s two breakaway regions in Donbas, would be recognised as independent. The minister had a dark look on his face, as if he already knew what was to come. Well, it’s hard to imagine that the defence minister didn’t know — it was Shoigu who led the full-scale invasion of Ukraine three days later.

Shoigu was almost immediately sanctioned by the European Union. The UK, Canada, Switzerland, Australia, Japan, and New Zealand followed suit soon after, while the US put him on the list of the specially designated people and OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control) persons. His wife and daughters would also make it to the sanctions list.

Shoigu and the 2023 coup

When it comes to the successes in the “special military operation”, as the Kremlin refers to the Ukraine war, Shoigu’s subordinates failed to capture Kyiv “in three days”. They couldn’t do it in six months, a year, or even 18 months, either. But Putin did not rush to remove the defence minister or the General Staff chief Valery Gerasimov. Shoigu’s career would continue as usual but for the interference of Yevgeny Prigozhin, founder and financier of the notorious Wagner Group private military company.

Prigozhin’s patience was running low and finally he snapped after more than a year of battles. In video addresses and voice notes he loves ever so dearly, Prigozhin slammed and chastised the “special military operation” progress, Shoigu, and Gerasimov in the crudest and most obscene terms possible, while praising the Ukrainian army. The Wagner chief demanded ammo from Shoigu and accused him of enormous losses in the battle for Bakhmut.

Defence Minister Shoigu kept mum.

This clash ultimately blew up on 23 June when the Wagner Group rose up in a rebellion. “This scum will be stopped,” this is how Prigozhin heralded his “March of Justice” across Russian cities in response to an alleged missile strike on Wagner camps by Russian troops.

The FSB launched a criminal case against Prigozhin for his armed rebellion against the authorities. In just 24 hours, the Wagner Group managed to practically capture Rostov-on-Don. However, the march on Moscow fell short after the mercenaries abandoned this mutiny attempt at the request of the Belarusian leader.

Throughout these two days of the coup, Sergey Shoigu was nowhere to be found. Putin was addressing the nation on TV, slamming the Wagner chief’s actions as treason and a “stab in the back”. Prigozhin was communicating with the public via video addresses and voice notes. Shoigu was quiet as a mouse. Several Telegram channels reported that he allegedly was placed under house arrest in custody of the Russian Federal Guard Service.

Sergey Shoigu’s first public appearance following Prigozhin’s coup. Photo: video screenshot

The Russian Defence Ministry decided to show Shoigu, alive and well, only two days later. The agency published a video where Shoigu reportedly was “inspecting a forward control post of the western grouping of troops in the special military operation zone”. It is, however, unclear when the video was recorded.

Shoigu and his future

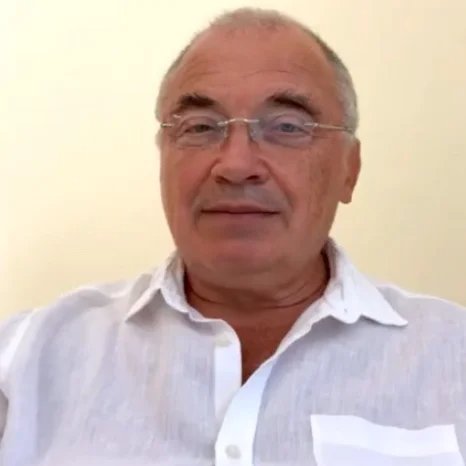

Novaya Gazeta Europe surveyed experts to find out what the future holds for Defence Minister Sergey Shoigu, 68.

Nikolay Petrov

head of the Centre for Political-Geographical Studies, Visiting Researcher at the Foundation for Science and Politics in Berlin

“In fact, the future of Sergey Shoigu became almost clear on 24 February 2022. He was never an effective statesman, he was always an efficient PR-manager. And when it came down to showing some real results and efficiency (as he was forced to), it turned out that Shoigu was not on top of things.”

“Putin avoids showing that he takes any steps, primarily about his staff, under the influence of external forces. In this case, under the influence of Prigozhin’s coup. Therefore, it is very possible that Shoigu will be removed, but it’s also possible he won’t be. His role as defence minister is decorative rather than functional. Therefore, he does not and cannot have any bright future politically speaking. I reiterate, his career as a politician ended on 24 February 2022, that’s when he was done.”

Sergey Shelin

political and social analyst

“Removing Shoigu is a perfectly natural decision if Putin wants to continue the war or even try to draw Ukraine here somehow. This is a decision that the regime needs to make.”

“But Putin is just not used to shuffling his people after they go bankrupt. He assembled a whole team of talentless, yappy, and worthless characters around him.”

“Shoigu represents somewhat of a test for this system now. If he is axed immediately, it won’t be Putin’s style. This move will indicate that Putin is no longer an independent person, he no longer makes decisions, he was pressured by some clandestine associates that forced him to appoint a more competent, as they see it, manager.”

“Another option: Putin himself realised that Shoigu needs to go. But then he has to do so in a month and not now to feign independence. This will be an indication that Putin is still a dictator.”

“There’s also a third option. Putin does not fire Shoigu and decides to stick with him. That would be a completely incompetent and inadequate decision that will accelerate the rot and collapse of the regime.”

“And it will seemingly reflect in new defeats on the frontlines. But that will be a very Putin thing to do. These are the three options I see.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]