We’re publishing this article in collaboration with Kedr.media

Chapter 1

’Such things happen only in Russia’

Svetlana Polyakova, 52, a meteorologist from Bichevaya, a taiga village in the Khabarovsk region, likes to sleep as long as she can in the morning, even though she then has to literally jump out of bed and hastily prepare to go to work. Her working day begins at 8:30 AM.

On December 9,2022, she woke up at eight in the morning. She dressed in a hurry, ate biscuits and washed them down with tea on the run, got from the heated hut into the freezing cold, and headed to work through the crunchy snow.

Walking down Gogol Street, Svetlana reached the crossroads, where she bumped into a tiger. As gamekeepers found out later, it was a female. “It felt unreal the first few seconds,” Tatyana recalls. “I’ve used the same route to get to work for thirty years, and now there’s a tiger.”

Svetlana and the tigress stared at each other, both absolutely stunned by the meeting. It flashed across her mind, “Wow, how beautiful you are!” There was not a living soul except for the two of them in the street.

The tigress lunged and roared at Svetlana, and the woman whispered almost unconsciously: “Jehovah, help me, Jehovah, help me.” After that, the tigress looked around and darted across the road and into the village.

Having come to her senses, Polyakova rushed to take pictures of the tigress’s tracks in the snow, worrying that nobody would ever believe that she escaped a rendezvous with a predator without a scratch. She shouldn’t have worried — seeing as the incident happened near a neighbours’ home equipped with outdoor video cameras, one of them caught the moment when the tigress ran past Polyakova.

Having photographed the tracks, Svetlana recorded a voice message in a local WhatsApp group to warn all the neighbours: “Have just bumped into a tiger on the crossroads. It jumped over the fence and ran toward Fifth Street.” After that, a curfew was declared in the village, women with children locked themselves in, and local hunters along with hunting inspectors started chasing the tigress out of the village. The scared tigress would cling to the ground, just like a normal cat, or rush around the streets. She accidentally tore a net and broke a fence near someone’s house. Irina Samodurova, head of the village administration, strictly told local television: “Certainly, she is a beautiful and gracious animal, and everyone was amazed, but people’s safety is above all.” Still, the tigress returned to the village the very next day and mauled a local resident’s dog to death.

Following the meeting with the tigress, Svetlana eventually made it to work and performed her duties all day. She works as a senior technician at a local meteorological station. She is supposed to take readings of special instruments, make observations, and draft reports. Long-term weather forecasts are made in Khabarovsk based on data collected from different parts of the region.

Svetlana Polyakova near her house. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

Svetlana and her husband Yevgeny live in a small wooden house shared between two families. Yevgeny Polyakov used to work as a radio operator at the same meteorological station, that’s where he and Svetlana met. His job was to send weather reports to remote stations around the taiga, but now he works there as a security guard. “Well, with all those WhatsApps and Telegrams you have now…,” he sighs good-naturedly.

The living room in the Polyakovs’ home is furnished with simple and well-worn furniture — a sofa, a table, a cupboard — and a large plasma TV in the middle, tuned to a state-run news channel. Firewood crackles in the stove, Yevgeny stirs it with a poker from time to time — sparks burst out. Amid our conversations in the kitchen, Yevgeny looks into the room now and then so as not to miss anything important. This TV occupies a large place not only in the house, but also in the lives of its owners. The village where the Polyakovs live is located in the middle of the taiga 130 kilometres away from Khabarovsk. The couple travels to the city once a year at most, and it is from the TV that they learn about everything that happens in the world.

No sooner had I entered the Polyakovs’ house than Yevgeny treated me to well water, while Svetlana hurried to get dressed to show me the place where she encountered the animal.

On the way to the scene, Svetlana once again recounts how it all happened — how she saw the tigress, how the animal roared, and how her own eyes widened at that moment. As she says, after she told local reporters that Jehovah had saved her from a tiger, “it encouraged God’s people all over the world” and “brothers and sisters” started writing to her from everywhere.

They were delighted that it was Jenovah who Polyakova thanked rather than attributing her salvation to good luck. As we walk, she turns on audio messages [from people who got in touch with her — translator’s note] for me. In one of them, a woman with a thick foreign accent says in Russian: “My dear Svetlana, this is Francesca from Rome. Did you know that you have family in Italy? Ha-ha. I thought, really, only God can help in such situations. And you just said it. Wow, you met a tiger. I can only imagine what you felt at that moment… I also want to go to Russia, because such things are impossible anywhere else except Russia. Darling, big greetings to you from Rome, the eternal city. Bye-bye.”

“My circle of friends has been growing,” Svetlana Polyakova sums it up.

After encountering the tigress, Svetlana says her attitude towards predators hasn’t changed, so she keeps going to work without any protective means. Her husband Yevgeny is a different story. On the day when his wife saw the tigress, he rushed to a local store for firecrackers, to be able to at least scare the beast away should anything happen, but it was too late: fellow villagers bought them all within hours. Yevgeny now goes to work only with a headlamp on flashing mode in front and on the back of his head to scare a tiger away, even though at nine in the morning, when he usually goes to work, it’s no longer dark outside.

Chapter 2

‘Ecology has been disrupted, food chain broken’

In 2010, Vladimir Putin proclaimed himself a protector of the Siberian tigers, also known as Amur tigers, and declared the preservation of their population in Russia a key national goal. An international Tiger Forum was also held in St. Petersburg at his initiative at the time (“the first in history,” as he proudly spoke about it). The participants shared their concern about the fact that the number of tigers in the world had declined from 100,000 to just 4,000 over the previous hundred years. The countries where this rare predator was still preserved agreed to double its population in their territories by 2022. The Russian government decided to spend about $54 million on this. Why the plan was to precisely double the number of these tigers remains a mystery for some scientists to this day. Kommersant journalist Andrey Kolesnikov, who attended the summit, speculated that “the declaration was prompted by the mere magic of digits,” that is, if said number needed to be increased by 2022, then make it 2 times.

An autonomous non-profit organisation called the Amur Tiger Centre was established at Putin’s initiative in 2013. Per its website, its goals include studying the Amur tiger, preserving and increasing its population, and establishing harmonious relations between the animals and the people living in the same areas. The Centre’s supervisory board, which determines its strategy, is full of government officials rather than professional zoologists, among them Justice Minister Konstantin Chuichenko (the supervisory board chairman), deputy head of the United Russia Party’s Central Election Commission Dmitry Nekrasov, chief of the presidential directorate for public relations and communications Alexander Smirnov, and others.

Nine years later, managers from the Amur Tiger Centre reported that the number of tigers in Russia had been increased precisely as was agreed before, that is, doubled.

A tigress with a six-month-old cub. Birsky Reserve, Khabarovsk region. January 2022. Photo by Sascha Fonseca

In his video address to the participants of the 2nd International Tiger Forum in Vladivostok in September 2022, Putin said quite predictably that “many of the common goals set then [in 2010] have been achieved.”

He also pointed out that “in some countries, the tiger has nevertheless disappeared since the last summit, in some others its life is still endangered,” while “in Russia, we have something to be proud of.”

“Twelve years ago, no more than 390 adult Amur tigers lived in our Far Eastern taiga, and now there are about 750 of them, together with cubs. This is the result of systemic measures implemented at the state level,” he said.

Khabarovsk scientists speculate that there are still fewer tigers in reality than was stated in the report presented to Putin. However, what they are more concerned about now is the fact that, having set themselves the goal of increasing the number of tigers, officials did not care whether the Ussuri taiga, tormented by barbarian logging, will be able to feed so many predators.

Logging at Birsky Reserve, Khabarovsk region. February 2022. Photo by Sergey Kolchin

Amur tigers live in mixed broadleaf and cedar forests in the south of the Far East, predominantly on the Sikhote-Alin Ridge. In the past fifty years, trees on which herbivorous animals feed have been steadily cut down here, within the Amur tiger’s range. This has seriously disrupted food chains in the ecosystem, where wild boars eat nuts and acorns and are eaten by predators. Moreover, African swine fever has decimated the already small number of wild boars in the Ussuri taiga in recent years.

As a result, hungry predators have been entering villages almost every day since November 2022. In the evenings, and lately even at daytime, they come into people’s backyards, take away chained dogs and eat livestock in pens. Some schools in the Khabarovsk region have transferred children to distance learning. Local villagers have no chance to defend themselves on their own, as anyone who kills an animal listed among endangered species and fails to prove that they did it in self-defence may be imprisoned for up to four years or fined up to one million roubles (€11,000).

According to the Khabarovsk region hunting inspectorate’s official data, the situation has seriously worsened over the past five years. The number of conflicts between people and tigers increased from 30 in 2017 to 95 in 2022, and January and February 2023 alone saw as many as 106 such incidents. Tigers stole 15 dogs from villages during the winter of 2020-2021 and 147 from December 2022 to mid-March 2023. In search of food, predators have visited at least 74 localities.

Having lost all hope to get protection from local officials, residents of the Nanai district wrote a letter to Putin in February (signed by 631 people), asking him to protect them from hungry tigers. As they put it, decisions concerning tigers are made in Moscow, while local authorities only give them advice on how to behave when a tiger has already arrived: don’t turn your back on the animal, don’t look it in the eye, walk around the village with a tambourine, and so on. “The ecology has been disrupted, food chains broken, and now we are facing consequences in the form of emaciated tigers, who come to villages in search of food and get it there. They cannot be blamed for this, as they are driven by the instinct of self-preservation, they want to live. And there is no food for tigers! And the time when people will end up being the only food for tigers is drawing near,” the letter says.

Lawmakers from the neighbouring Lidoga rural settlement followed suit by addressing the president asking him to protect the people.

Four-month-old tiger cubs who starved to death under the porch of a house in Shumny, Khabarovsk region. December 2021. Photo by the Khabarovsk Regional Natural Resources Ministry

Not only have tigers been leaving the taiga in search of food lately, but they have also died under the wheels of cars and trains, and small emaciated tiger cubs have been found dead under porches of houses in the villages. Independent scientists have warned that the tiger population in Russia is on the verge of a deep crisis.

Chapter 3

A shaggy tiger breaks into the house

Victoria Ludannaya demonstrates the height of the tiger who ran into her house. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

Victoria Ludannaya, 60, a postal worker from the village of Shumny in the Khabarovsk region, was cooking dinner on a December evening in 2022. Having suddenly heard dogs barking, she realised immediately, considering what had been happening in the previous weeks, that a tiger was somewhere nearby. Her one-year-old chihuahua named Umka was rushing towards the house “with a frantic bark”. Ludannaya dashed toward the door to let her in. Umka ran into the open door, followed by a shaggy tiger, as Victoria recalls now. She has a pass-through corridor in her house. The “horrified” Umka ran out into the street through the next open door, the tiger behind her. As Ludannaya says, she was “struck by shock” for a moment, but in order to save her beloved dog, she immediately grabbed a mop and, shouting profanities, chased the tiger away. The frightened beast escaped her backyard. Hearing his mother screaming, Victoria’s son ran out of the bathhouse and saw it all happen.

When tigers come to villages in the Khabarovsk region and, as locals say here, “crush” their domestic animals, people call the police. If they can prove that their dog, horse, or cow was killed by a tiger, the Amur Tiger Centre is supposed to provide compensation by replacing the dead animal with an identical one. However, not many have managed to receive such compensation.

Police officers took pictures of the crime scene and the victim, Umka. While running away, the tiger hit the dog with its paw, knocking out her eye. She agonised all night and died the next morning. Victoria remembers that the tiger was as high as her waist, and yet she insists she was not scared. “It’s not like I’ve never seen tigers before,” she says in an annoyed voice.

Chapter 4

‘I was paralysed with fear: what if a tiger is behind my back?’

Tatyana Sheremet, 61, an elementary school teacher, lives together with her husband on the outskirts of the village of Kiinsk in the Khabarovsk region. The frozen Kiya River passes right near her house, which abuts a forest. Hearing my knock at the door, her husband Sergey wonders jokingly, “And who’s out there? Tigers again?”

On the morning of February 18, on his birthday, the Sheremets’ son came down to his parents’ from the city. He gave his mother a bouquet, the family switched on the TV and drank tea with a cake. Twenty minutes later, Sergey walked out of the house and saw a tiger’s tracks upon the fresh tracks of his son’s car. He looked at the doghouse and saw only an empty chain on the snow. His hunting dog was gone. Even though Sergey had hunted all his life, now he broke out in a cold sweat. “Well, you know how cats can creep up silently, and I was paralysed with fear: what if a tiger is now behind my back? What if it snatches me by the collar and takes me away?” he recalls.

Having overcome his torpor, Sheremet ran back into the house, and the spouses called the police. They spent the entire day making sure that nobody walked upon the tiger’s tracks before the local police inspector’s arrival, but he never arrived.

The villagers appealed to the hunting inspectorate and the head of the village administration to protect them from tigers. The head took their petition to the prosecutor’s office, from where he was referred to the district administration, and then to the regional governor in Khabarovsk. And this is where everything stalled.

“Sergey, as a hunter, tell me what is to be done with tigers?” his wife asks him. “And what am I supposed to say, for God’s sake?” Sheremet is getting worked up. “The president has ordered breeding them, and who cares what I think. There are 140 tigers in the Khabarovsk region now, and if anything happens, you can’t shoot at them. Try and prove then that it was self-defence. There’ll be even more of them in a year, but the number of wild boars or Manchurian wapitis is not growing in the taiga. All ungulates in the reserves have long been done away with, and only workers are left.”

Sergey Sheremet shows a tiger's tracks in his yard left two weeks before. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

Despite regular reports about predators roaming villages, the Amur Tiger Centre keeps pretending that nothing out of the ordinary is happening. It says there is enough food for tigers in the taiga, and they have just grown lazy and do not want to hunt, and instead go to villages for dogs, while villagers fail to chain their dogs and leave waste dumps open. Moreover, the Centre has gone as far as to claim that dogs themselves are to blame for being killed by tigers, as they provoke predators by their very existence. “Stray dogs are a direct threat both to people and to those wild animals that cannot defend themselves, unlike a tiger or a bear.” To uphold its point, the Centre has even posted a video on Telegram showing “a deer that was attacked by a pack of dogs and eventually died”.

At the same time, the Amur Tiger Centre has regularly tried to convince either Putin or the residents of the villages visited by predators that not so many tigers actually show up, but rather people themselves have spread “tiger fakes” by posting and sending each other old videos in which tigers come into villages, “passing them off as new ones”. The Amur Tiger Centre did not reply to Novaya-Europe’s request for comment on the tiger situation.

Tiger stole a tethered watchdog. Outskirts of Bolshekhekhtsirsky Reserve, Khabarovsk region. December 2014. Photo by Sergey Kolchin

Since March 2023, Russian courts have started fining locals for “tiger fakes”. The Primorsky Court has fined a man 50,000 rubles (€550) and ordered his mobile phone be confiscated for WhatsApp and Telegram posts about a tiger entering a local village.

Zoologists Sergey Kolchin and Viktor Lukarevsky dismissed the claim that tigers coming to villages are driven by laziness rather than hunger as “outright stupidity”. They both insisted that tigers are cautious animals who fear humans and will never approach them unless they absolutely have to. Kolchin says the fact that tigers started regularly entering settlements this winter demonstrates that this is their last chance to survive.

Biologist Alexander Batalov agrees. “Tigers are not lazy animals, they can go up to a hundred kilometres. And they are not scavengers, unlike, for instance, bears. They need fresh meat. Therefore, if they come to dumping grounds, then only out of hunger.” Wild boars are the main feed for tigers. They are fat, a tiger can easily catch them, and there are many of them. However, seeing as there are almost none of them in the taiga left, tigers have to prey on other ungulates. But their number in the Khabarovsk region has also dropped critically.

Tiger’s range is covered with a dense network of roads enabling hunters and lumberjacks to reach the most remote parts of the taiga. In the valley of the Durmin River, Khabarovsk region. January 2020. Photo by Sascha Fonseca

Batalov hates to see how the blame is shifted onto villagers. “What do untethered dogs have to do with this?” he gets angry. “The empty taiga that prompts tigers to come to villages is not the villagers’ fault. And besides, with tigers regularly coming to villages, a tethered dog is doomed.”

What worries scientists and hunters is that tiger managers keep publicly denying the problem. “The president needs to know what is really happening,” says Batalov. “He should order the urgent restoration of the animal’s habitat.”

“They’re increasing the number of tigers for purely political reasons, so as to tell the whole world later: look what a great country we are,” suggests Batalov. He believes, however, that there is no reason anymore to try to increase their numbers in the current environmental situation. “You need to assess how many fodder trees are left and how many wild boars and other ungulates can actually feed on them, and then you’ll see how many tigers you can keep in their range so that they could have enough food and not go to people,” he says.

“Tiger managers can still shield themselves with dogs, who are taking the hit, but who’s next? Humans?” Kolchin says.

Chapter 5.

‘We need to satiate the taiga’

Secondary plantations of aspen and birch formed instead of mixed cedar and broadleaf forests after felling have low food and protective value for most of the taiga inhabitants. The valley of the Durmin River, Khabarovsk region. March 2022. Photo by Sergey Kolchin

In the 1930s, logging settlements began to appear in remote taiga parts of the Khabarovsk region. People from across the USSR rushed there for various reasons. Anatoly Stepnykh moved there in the late 1970s to head a state purveying farm for many years.

No matter how difficult it was at the time, now he remembers those years as comfortable and happy. “You can’t imagine how much stuff we purveyed! Hundreds of tonnes of fern, birch sap, honey, crude medicine, eleutherococcus,” Stepnykh recounts. “Our farm offered the highest salaries then.”

In the 2000s, the farms were liquidated and the forests were leased out to businesspeople. The staff of the forest guard has since been reduced. Numerous state functions have been delegated to private logging operators, and most of them think only one day ahead. “They have been made responsible for reforestation, but they just don’t care what happens to this forest after their lease expires,” Stepnykh says.

The leaseholders of local hunting grounds live by selling vouchers for hunting ungulates and other animals. By overstating the number of animals, as Stepnykh says, they get more licences to shoot them from the state and sell more vouchers to hunters. “If you believe their reports, you would be unable to enter the grounds without being trampled down by wild animals,” says Stepnykh, who earlier served as a senior state wildlife protection inspector. “All these reports go to Moscow, and Moscow then talks on the TV how everything is flourishing here. The top-down system here is the same as elsewhere. Why would things be different here?”

Wild boar, primary prey for tigers, especially younger ones and females with cubs, has now virtually become extinct in the Ussuri taiga. In the valley of the Durmin River, Khabarovsk region. November 2006. Photo by Sergey Kolchin

Stepnykh says the spread of African swine fever began in the Far East in 2019. That was when a directive came from Moscow to reduce the number of wild boars as much as possible. Many hunting providers in the Khabarovsk region saw this as a chance to make a fortune on selling an unlimited number of vouchers to cull wild boars. “Hunters having these vouchers got legal permission to be in the forest with firearms up until January 2023, shooting not only the remaining wild boars, but also deer, bears, and other animals. In fact, it was legalised poaching,” Kolchin confirms. “In the absence of proper control, no one monitored who exactly hunters killed there and in what quantities.”

This winter, when hungry tigers started regularly showing up in villages, Yury Kolpak, acting head of the Khabarovsk region hunting control department, finally realised there was a problem, which could no longer be swept under the rug. He reported to the federal Natural Resources Ministry (Novaya-Europe possesses a copy of the letter) that “multiple instances of tigers entering settlements and attacking domestic animals have been recorded in the Khabarovsk region”.

Kolpak attributed the upsurge in incidents involving tigers to “the disastrously low numbers of wild boars”. To protect locals, he asked for the federal Natural Resources Ministry’s permission “to extract six Amur tigers from the wild” and prohibit the cutting of Mongolian oaks and the hunting of wild boars for three years.

At the end of February 2023, the federal Natural Resources Ministry approved the ban on hunting wild boars and ignored the request for banning the cutting of oaks.

Logging in Birsky Reserve, Khabarovsk region, one of the most important territories for tigers. February 2022. Photo by Sergey Kolchin

In the past century, mixed cedar and broadleaf forests in Russia’s Far East, particularly the Primorsky region, where the Amur tiger’s population is mainly concentrated, have been reduced by about two-thirds.

The last surviving areas of ancient forests, where logging was prohibited in the Soviet years, are being cut down these days. Loggers have long been developing even regional reserves, which were created, in particular, to protect the tiger and its habitat.

“The president calls for protecting the tiger, but nobody has managed to explain to him that tigers can be preserved only through preserving the environment,” Batalov says. “If you decide to preserve the tigers and even increase their numbers, then you need to know how you will be feeding them.”

“The minister of natural resources proclaims on TV: ’We are a forest country.’ But we actually don’t have any forests anymore! All of them have been wasted from Vladivostok to Kaliningrad! Look at what’s happening in Siberia, in the Krasnoyarsk region, or in the Irkutsk region. Absolutely all of it has been wasted and stolen. And corruption governs everything.”

Batalov, a 71-year-old gamekeeper living at an observation outpost, says tigers are “like drug addicts”, looking for the last wild boars in the taiga all winter, while lumberjacks are looking for the last oaks. As Batalov put it, “the Chinese are hunting” for these trees to make furniture and sell it at a high price. “Apart from the fact that oak furniture is practical, the Chinese believe that people who sleep on an oak sofa will live long, receiving the energy of longevity from a tree that lives 100 to 150 years itself,” he says.

Moreover, Russia offers China good terms, Batalov says. “The Chinese buy oak wood in Russia at $800 per cubic metre and then export it for five times the price.”

About ten areas in the Khabarovsk and Primorye regions have high nature conservation status where, according to scientists, “the situation is relatively favourable.”

“But the tiger is a big predator that needs large territories. When a tiger cub grows up, it goes out to look for its place under the sun in order to acquire its own territory,” Kolchin says. “Leaving the reserve, it soon finds itself at a felling site, where no food is left for it. Then it goes to villages for food. Even though new protected areas have been created in the past few years, it is not enough for preserving the population. Being isolated from each other, they become not so much reproductive centres as ‘breeding grounds’ of tigers prone to conflict.”

“Simply banning wild boar hunting is no longer enough,” says Batalov. “It may sound utopian, but we need to set up farms for breeding wild boars outside the tiger’s range and then release them into the taiga. We should also stop cutting down Mongolian oaks, ashes, walnuts, and other fodder trees to enable wild boars to feed and breed in the forests. To improve the situation, not to mention increase the tiger population, we must satiate the taiga first.”

Chapter 6

‘Tiger’s home’

The village of Uni where the Udege people live. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

The village of Arsenyevo, which was my next stop, is surrounded by the taiga and hills. To the left, across the Uni River, live the Udege, one of the indigenous minorities of Russia’s Far East. A community of Old Believers lives a little away from the village. To get to Arsenyevo from Khabarovsk, you need to drive 150 kilometres along the Khabarovsk — Komsomolsk-on-Amur highway and then another 60 kilometres through the dirt road deep into the taiga. On both sides of the road, you can see tracks left by hares, foxes, tigers, and God knows who else in the snow.

Most of Arsenyevo’s residents are Russians, who once came here in search of work and stayed, and children and grandchildren of Ukrainians, who were exiled here in the 1950s by whole villages.

Igor Kyalundzyuga, a 62-year-old Udege man, says he could not remember any conflicts between Russians, Udege, and Ukrainians living on this soil.

There are almost no jobs either here or in neighbouring villages. Nobody hires locals for logging these days, as the previous amount of workforce is no longer needed. “And even if you give someone a job, they aren’t going to work but will only drink,” Stepnykh admits. Keeping cattle has become unreasonable because of expensive feed and fuel. The average salary in the area is 20,000 rubles (€220) per month.

Sometimes villagers leave to work on a rotational team basis, but more often, they get food in the taiga. Just like in other local villages, men hunt wild boars, deer, bears, and furbearers, often illegally. Some fish, even though it is forbidden, some keep apiaries. Women collect and sell wild berries and herbs. Collecting cedar cones, some manage to earn 300,000-400,000 rubles (€3,300-4,400) over a summer.

Adult tigress. Khabarovsk region. October 2022. Photo by Sascha Fonseca

More than 80% of the Amur tiger’s range today is allotted for hunting grounds, meaning that people and predators have to compete for food there.

Humans and tigers hunt the same animals. Sometimes hungry predators walk along hunting paths and eat the bait in traps set up for sables — and often fall into these traps themselves. Adult tigers free themselves by breaking traps, sometimes injuring their fingers in the process, but cubs cannot escape from a trap and have to wait until they lose their fingers to frostbite in the trap so that they can finally pull the paw out.

Local hunters often feel real anger towards tigers, as if they competed as equals. It even happens that, spotting a tiger in the taiga, they shoot it in the stomach from a car, prompting the wounded animal to retreat deep into the taiga and die there, so that they could not be blamed for this.

On February 12, Udege cousins Sergey Sigde, 19, and Alexander Sigde, 22, were dressing squirrels in a hunting lodge in the taiga. At that moment, breaking the window, a tiger burst into the hut and attacked Sergey. Alexander grabbed a carbine and shot the animal. This is the account that the cousins gave to fellow villagers and police officers, who opened a case into the death of an animal listed among endangered species.

It took about a day and a half before Sergey ended up in a Khabarovsk hospital. He spent several days in intensive care, then sepsis began, and his arm had to be amputated. Sergey was the only breadwinner in his family getting food for his relatives in the taiga. His mother, disabled from childhood, also has two 14-year-old daughters and a younger son, who is currently in the hospital with tuberculosis.

Viktor Sigde near his home. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

The circumstances of the tiger’s attack presented by the cousins immediately looked suspicious to local hunters. They know for certain it is atypical for a tiger to attack by bursting into a dwelling; as a cat, it would rather ambush its victim from around a corner, and therefore, the cousins must have provoked such behaviour.

A month later, Alexander confessed to the police that, before the tiger jumped into the window, he had seen the animal outside, was frightened, and shot him, after which the wounded beast broke into the hut.

Investigators discovered another week-old wound on the dead animal’s body and retrieved a bullet fired from the same gun. Then Alexander admitted that, three days before the incident, he had noticed the same tiger following his cousin’s trail, got scared, and shot into the air to chase it away. He is sure, however, that he could not have hurt the animal.

On February 13, a message posted in a village chat on behalf of the Sigde family said that Alexander had been forced into confessing to something he did not do. “If they acknowledge officially that a tiger can break into a human dwelling through a window, no one will feel safe in their homes. They need the Udege, who will soon be outnumbered by tigers in the Khabarovsk region, to take the blame. We ask the authorities and everyone who is in charge of protecting tigers: if you care so much about tigers, then why don’t you feed them? Is it really that difficult to buy livestock and release it into the taiga? Breeding the tiger uncontrollably, why do you allow such terrible logging? After all, the forest is the tiger’s home,” the message says.

Chapter 7

Only cowards survived

Tiger whom hunters nicknamed Ochkarik (Four-Eyes) for the ornament near his tail head resembling spectacles. The valley of the Durmin River, Khabarovsk region. October 2017. Photo by Alexander Batalov

When Russian colonists started settling in the southern part of the Far East in the second half of the 19th century, they would shoot all predators who did not show fear and behaved calmly and confidently — either in the taiga or near settlements. It just so happened that all the bravest ones were killed, and only the cautious ones survived. “It’s been suggested that, in fact, that was a years-long selection of cowardly animals, who then brought forth cowardly offspring,” zoologist Sergey Kolchin says. Apart from that, cubs are inclined to copy their mother’s behaviour, and if she acts cautiously and avoids humans, roads, and settlements, then the cubs would follow suit. “According to my observations, the main and the only thing that local tigresses teach their young is fear. Fearing humans,” says zoologist Viktor Lukarevsky, who has studied felids nearly all his life.

“While in a forest, a predator is the first one to notice a human, so it hides unnoticed,” Kolchin says. “This explains the stories of hunters who have spent their entire lives in the taiga and have never seen a tiger. This just means that tigers would notice them first and leave.”

Igor Kyalundzyuga near a stack of oak wood in Arsenyevo. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

Igor Kyalundzyuga, an Udege man, knows that tigers do not normally attack people or enter villages. “Perhaps the same goes for people, who don’t normally roam the taiga looking for food,” he notes. “But hunger changes the behaviour of both humans and animals. We go to the taiga to hunt their deer and wild boars, and they enter our villages to crush our dogs and horses. Few would agree just to wait and die. We are predators, we simply want to survive.”

Kyalundzyuga complains that “you keep ramming it into your children until they’re 35 years old that you should live on your land, but they leave anyway, because there are no jobs and no proper conditions”.

Then he adds after a pause, “Well, who knows, maybe you just shouldn’t live where you can’t remain human.”

The prices for groceries at the shop in the centre of the village are about twice as high as in Moscow.

A leaflet posted in the shop invites locals “to join the General Korf Battalion”. It promises volunteers a one-off payment of 250,000 rubles (€2,750), prioritised enrolment of their children in kindergartens, prioritised admission to a vocational school and then to a university, and a one-off payment of 50,000 rubles (€550) per child.

Kyalundzyuga calls the head of the village administration, Igor Lonchakov, to ask him to talk to me “about the tiger”. Lonchakov yells back on the phone: “I am sick of hearing about that tiger, I’ve got another problem right now!” The day before, the locals learnt that the first mobilised soldier from Arsenyevo, a 36-year-old man who worked at a power plant, had been killed in early February.

The people are deeply confused about what they can and what they cannot say, and what they should call things. Several people from different villages would start saying “war” and, looking at me, would immediately correct themselves to call it “a special military operation”. When they talked about Putin, they would say “he”, meaningfully pointing their finger somewhere upwards.

A school employee — her neighbours told me that she was “scared of tigers to death” — does not immediately agree to talk, as if trying first to decide what she fears more: tigers or being punished for telling a journalist about them. “You see, I work at a school,” she says. And we both understand what that means.

Arsenyevo school. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

The school is very cosy, its walls are painted soft lilac; in the Russian language and literature classroom, I see an accordion on a cabinet and a portrait of Leo Tolstoy on the wall. The school employee (we agreed that I would refer to her this way in my story) tells me that the tiger situation has been tense since the end of last fall. The residents of Arsenyevo try to finish their business outdoors by six in the evening. “If you have to walk out at 6:30 PM, you feel kind of uncomfortable and uneasy,” she says. “I come home from school at six and hurry to kindle the stove and feed the dog. I walk out, and the silence there is literally deathly. You want to give the dog food and come back in very quickly, because this silence really presses down on you.”

The first time tiger tracks were noticed in Arsenyevo was near the kindergarten’s gate in November 2022. A school worker then called the education department to ask its head what to do. She suggested that the children “walk to school singing, take their speakers with them, shout, and make noise along the way”.

In addition to local kids, the school in Arsenyevo is attended by another twenty children of Old Believers and seven children of the Udege people from the neighbouring village of Uni. To get to the school, they need to pass “through the woods”. As soon as it gets dark, messages start appearing in local chats: “A tiger is breaking into your gate”, “A tiger is walking along Zelenaya Street”, “A tiger jumped into Alice’s yard and snatched the dog”, “How long can all of this continue? We need to take some measures”, “My kids won’t be attending school because they are afraid of tigers”, “Dear parents, what do we do about the children?” And all these messages are occasionally interspersed with images of tiger tracks in the snow and torn-off dog heads on a chain.

In reply to petitions from Arsenyevo residents, regional officials only suggested that they install three-metre-high metal fences. “Nobody here has enough money for such fences, and besides, it’s not an obstacle for a hungry tiger,” the school employee says. “I myself saw a tiger throw a dog over a high fence.”

Igor Kyalundzyuga’s yard. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

Residents of Arsenyevo, as well as their neighbours from other villages, have also been advised to let their dogs in at night. “We keep hunting dogs, and they are used to living outdoors. If I let her in, then there’ll be terrible stench from her all over the house. And besides, the dog will be happy to be let in for five or ten minutes, but then it will start scratching, barking, and asking to go outside, because it’s too hot for it indoors.” The locals have also been encouraged to walk around the village with flares. “But where can we buy them in our shop? And again, it’s too expensive,” she says angrily.

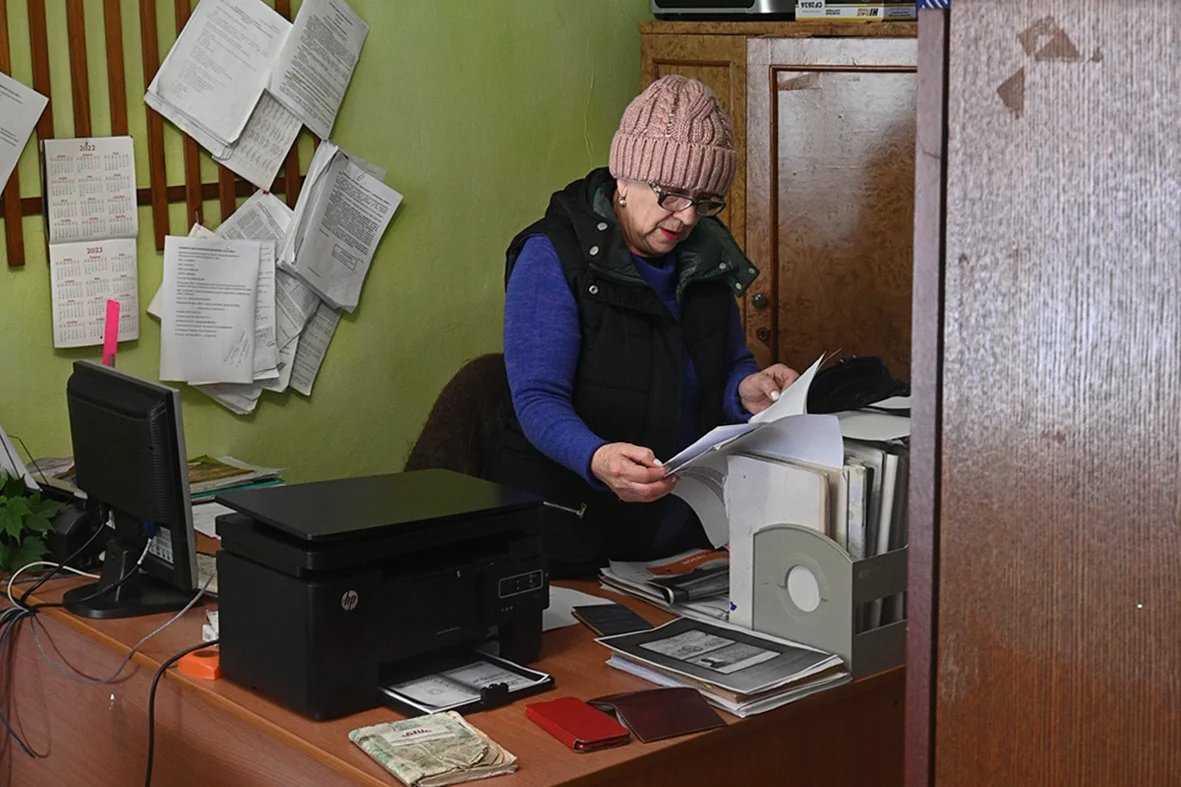

Stefa Dovzhenko at her workplace at Arsenyevo village administration. Photo by Irina Kravtsova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

The only thing the village administration head did to help his neighbours is allot a minibus to gather children and drive them to school twice a week. The villagers are sincerely grateful to him for that. On other days, a lot of children simply do not go to school: just like in some other villages in the Khabarovsk region, they receive their homework assignments online.

The head lives on the edge of the village. Stefa Dovzhenko, a social worker at the village administration, says, “He is a biologist by education, and he kept trying to convince everyone here that a tiger would never attack a human first. ‘That’s what is written in literature…’” Dovzhenko mimics him good-naturedly. “And then a month later he says, ‘You know, Stefa, I saw a tiger near my house.’ I ask him, ‘And how did you like it?’ And he replies, ‘I can’t even tell you what I felt… I was like paralysed. A stupor. Hard to express.’ ‘Oh, really? And did you recall your instructions on how to squeak and squeal? You would tell all of us that it’s written in literature.’ ‘Oh, what are you talking about,’” Stefa retells her conversation with her boss.

I catch village administration head Igor Lonchakov in the shop. He pretends to be an ordinary customer for some time before giving up and saying that “there’s no need to muddy the waters”.

“The governor, the relevant services, and hunters are perfectly aware that tigers come down to villages,” Lonchakov says. “Tigers also run around my home, and so what? Why shout it from the rooftops? I am a biologist myself, and I know that if I see it, nothing bad will happen to me, because it is scared itself.”

Asked about his encounter with a tiger, Lonchakov replies that he “wasn’t scared at all”.

“I didn’t do anything, just kept standing, and he ran away himself. They won’t harm humans. Tigers are almost as smart as dolphins,” he concludes suddenly.

In conversations with me, the villagers often repeat that Lonchakov (as he apparently tells them himself) is trying to defend their interests before the authorities, but they “don’t listen to him”. On the other hand, the village head assures me that people themselves are to blame for their conflicts with tigers. He insists that tigers would not attack people in the village, and there is no need for them to go to the taiga. “That’s right, we have everything we need in the shop. What’s the point in going to the forest?” Lonchakov asks me, pointing to the shop’s quite meagre assortment including sausage, tea, instant noodles, biscuits, and ready-to-cook fish in the freezer.

At the end of January, a young and hungry tigress would descend from a nearby hill, enter Arsenyevo, and walk up and down Third Street after dark for about ten days in a row.

As the school employee says, the locals informed “all of our institutions dealing with tigers” about the haggard tigress, but nobody responded for quite a long time. Then an official from the hunting inspectorate eventually arrived. The school employee recalls that the tigress tried to leave for her hill, but she walked along the road, for she had no strength to go through the snowy forest. “And then she became completely exhausted, lied down, and just looked around without uttering any sound, without roaring or otherwise manifesting some aggression, she just didn’t care anymore,” she said. “The hunting inspectorate’s vehicle approached her, but she couldn’t even run away, only raised her head, and that’s it.” The inspectors shot a tranquiliser gun to sedate the tigress and take her away for rehabilitation, but she was so weak that she never woke up.

Epilogue

Male tiger near a scent-marking tree. Birsky Reserve, Khabarovsk region. December 2021. Photo by Sascha Fonseca

All these years, the Amur Tiger Centre has been painting a rosy picture about its successes, like posting colourful photographs on social media or decorating planes and TV towers with its emblem. The centre of Khabarovsk is full of billboards saying ‘Tigers, thank you for your support’. Side by side with them are banners advertising circus shows featuring predators.

In the run-up to the abovementioned tiger forum in Vladivostok in 2022, three zoologists had published an article on Kedr.media, saying that, contrary to what tiger managers claimed, the population of the Amur tiger was endangered and needed urgent help. At the end of their article, they invited the Amur Tiger Centre to discuss the matter.

However, according to an employee of the research organisation where two of the authors worked at the time, instead of a discussion, the Federal Security Service displayed an interest in the zoologists. As was understood at the institute, special services were worried that the scientists might go to the forum and display banners saying that, contrary to official statements, the tigers were in trouble. One of the authors was on an expedition at the time, and the other was urgently recalled from vacation and given an assignment to do some research in a forest exactly when the forum was held. In the meantime, Putin told the forum participants via video link: “It would be really great if all subspecies of the tiger family lived in the same conditions as our handsome Amur tiger does. To ensure its stable future, we only need to resolve a few specific and practical tasks”.

There are as many as 750 Amur tigers, including cubs, in Russia. In search of free sites, young tigers are settling widely throughout the Khabarovsk and Primorsky regions. This inevitably makes tigers’ encounters with humans more likely and increases the threat of conflicts with the local population.

Tigers avoid meeting humans as much as possible. The growing number of conflicts with humans is typical primarily for the Khabarovsk region and should be chiefly attributed to a lack of food supply for the tiger. The reason is a sharp decrease in the number of wild boars caused by African swine fever and the intensive felling of oak plantations. While similar incidents within the tiger’s range also occur in other regions of the Far Eastern Federal District, they are much less frequent.

That said, the wild boar is not the only element of the Amur tiger’s food supply. In its absence, the predator switches to other prey, such as Manchurian wapiti, spotted deer, or roe deer. Expert observations have shown that the tiger’s diet has somewhat changed now, with the proportion of wild boar having decreased in favour of Manchurian wapiti, spotted deer, and roe deer. However, the density of these ungulates is quite low in the Khabarovsk region, in contrast to the Primorsky region.

The Russian Nature Ministry is closely monitoring the African swine fever situation and taking all necessary steps.

In the absence of conventional and available prey, tigers enter populated localities, where they can find easily available prey in the form of domestic and stray dogs.

Each encounter between a human and a tiger is considered potentially dangerous, and a task force is dispatched to the scene in such instances. Such task forces exist in each of the four regions within the tiger’s range. Potentially dangerous predators (i.e. sick, injured, aggressive, or unresponsive to deterrents) are removed from the wild and placed at a rehabilitation centre. In case of successful rehabilitation, such tigers are released back into the wild away from human settlements.

To minimise conflicts between tigers and humans, efforts are being made to increase the tiger’s food supply, including through biotechnical methods for ungulates. Experts instruct people living within the tiger’s range on how to behave when encountering one, and heads of municipal administrations in the Khabarovsk region are advised to make sure that all domestic animals are kept in enclosed spaces inaccessible to predators so as to discourage them from entering settlements. When a tiger targets livestock for prey, the owners are entitled to compensation for the damage they sustained.

The Amur tiger tops the food chain of the Far East’s wild nature and is a key indicator of the ecosystem’s state as a whole.

As the number of tigers increases, the number of animals at the lower levels of the food chain (tiger prey items) should grow correspondingly. Any decrease in their numbers can undermine and destabilise the ecological pyramid and increase the risk of conflicts. Therefore, seeking to increase the number of tigers, priority should be given to restoring ungulate populations, especially where their numbers and density are low.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]