While I was coming down the Lachin mountain serpentine, my phone started vibrating. It was someone from the Russian military base, which, as is commonly believed, maintains peace and security in the small part of Karabakh that is still controlled by the unrecognised republic.

“Andrey Valeryevich,” the man from the Russian peacekeepers base introduced himself shortly. “I was told you want to cross over to Stepanakert. Why?”

I explained that I had to see how people in Nagorno-Karabakh are living under the blockade organised by Azerbaijani eco-activists.

“The blockade?” Andrey Valeryevich chuckled. “They’re doing great, better than before! It’s us, peacekeepers, who’re under the blockade. The prices are crazy! Take a dozen eggs — three hundred rubles [€3.6] in Russian money. Isn’t that crazy? Three hundred! These ‘blockade victims’, these Armenians, are the ones selling us eggs at such prices!”

The man promised to call me back and then take me to Stepanakert. I never heard from him again.

“There’s a passage to get into Karabakh, but it costs money, 150 thousand [Armenian] drams [about €360] per person,” Armenian politologist Andrias Gukasyan tells me a few days later. “You have to first go to the Russian peacekeepers base in Goris. Why are you so surprised? You’ve come from Russia, you know what it’s like. Although I don’t recommend trying to use your Russian passport.”

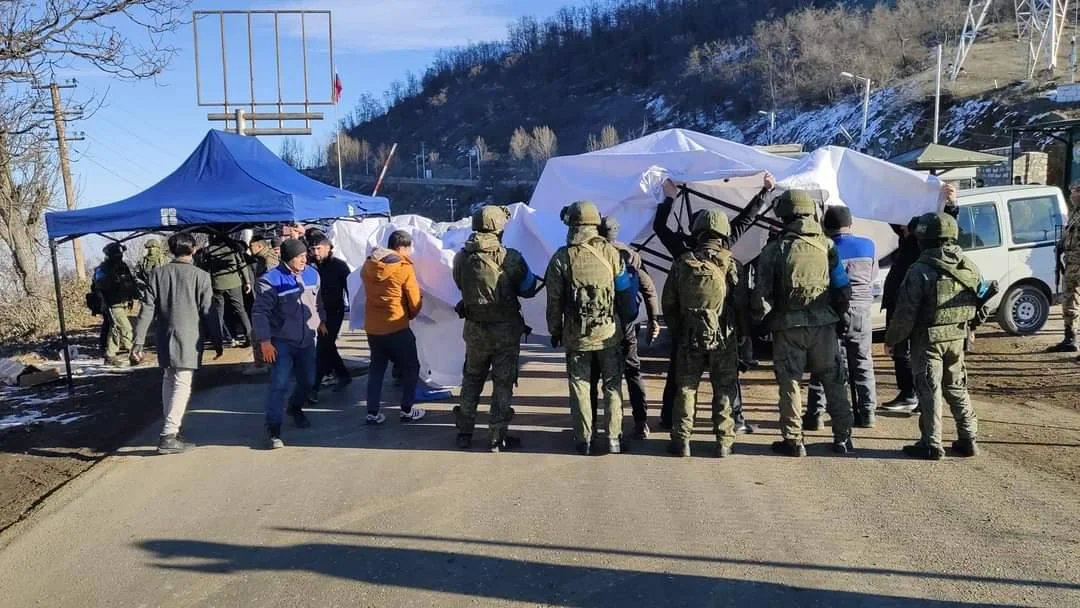

Azerbaijani ecologists setting up camp on the road connecting Armenia and Karabakh. The Lachin corridor, December 2022. Photo: Telegram

The corridor

Immediately upon leaving the Armenian village Tegh, my car stops before an automatic gate. Further away is the territory that has been under the control of Azerbaijan since November 2020. Inside it, there’s a little island — Stepanakert and the surrounding villages, a remnant of the unrecognised Nagorno-Karabakh republic.

From the Armenian side, the border is guarded by an Armenian military police post. This is where Karabakh’s blockade begins. There’s another post like that in Stepanakert, in between the two there are Russian peacekeepers and Azerbaijani “ecologists” who organised the blockade.

“I can’t let you pass further,” Misha tells me, shaking his head. Misha is a police captain who speaks Russian with a barely noticeable accent. “You go further, Azerbaijanis begin shooting, I go to jail because of you.”

A convoy of trucks with Russian military licence plates reaches the gate, coming from Armenia’s territory. Two trucks are white: it’s believed that Russian transport with humanitarian aid looks like that. Misha gives me a warning sign — I’m not allowed to take photos of vehicles.

The Lachin corridor. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

As a reminder, this is how the checkpoints came to be. After the Second Karabakh War in 2020, Stepanakert remained under the control of the unrecognised Nagorno-Karabakh republic while the territory around it was taken over by Azerbaijan.

Karabakh and Armenia are connected via the Lachin corridor in the mountains. The corridor’s width is stated at 22 km. In reality, it’s a narrow highway where even two cars aren’t always able to let each other pass. But in the mountains, it twists up in such loops that the total width of this serpentine can really reach a dozen or two kilometres. Moreover, the loops curl up and down, too. Driving here is hard and dangerous, so Azerbaijan is building very expensive roads from its side, carving tunnels in the mountains. For Azerbaijan, Karabakh is an opportunity to “put on a show”, like Russia does in Crimea.

Armenia has also promised to build a straight and safe tunnel, but compared to December 2020, when I departed Karabakh for the last time, the only thing to have changed on the road is the surface. Before, it was full of potholes; now, there’s good asphalt. Also, burnt tanks are no longer piled up on the slopes. This corridor amidst rocks and cliffs, this sole thread connecting the unrecognised Karabakh and Armenia, has been cut off.

According to the trilateral agreement signed on 9 November 2020,

Azerbaijan pledged not to interfere with Armenians’ coming and going to and from Karabakh. The corridor has to remain under the control of Russian peacekeepers, they’re the ones ensuring the aforementioned freedom of movement.

On 12 December 2022, the road was blocked by people from Azerbaijan. They referred to themselves as eco-activists who had to verify the compliance with the environmental protection norms on two Karabakh mines — the Drmbon mine and the Kashen mine. Apparently, the Azerbaijani ecologists were concerned about Armenians most definitely mining copper and molybdenum there and violating rules en masse, all that on the property of Azerbaijan. Everyone knows how much that country values environmental protection.

Thus, the corridor was blocked by two checkpoints — an “ecological” and a “peacekeeping” one. The peacekeepers are not letting ecologists enter Stepanakert, but they’re also not interfering with their blocking of the highway.

A month ago, on 22 February, the UN International Court of Justice in The Hague ruled that uninterrupted movement should be ensured across the Lachin corridor. Azerbaijan assures that the movement is already quite uninterrupted. Armenia claims that Karabakh remains under the blockade.

Stepanakert. Gayane Arustamyan

“I live with my elderly mum, and taking care of her has become much more difficult. Especially on the days they turn off the gas. Because we’re in constant need of hot water, and we have a gas boiler. Two days ago, the gas was turned off again,” local resident Gayane Arustamyan says.

“The blockade? Well, the road hasn’t been blown up. Lately, the food has been available. There are different grains, in general, one can get by. There’s flour, there’s bread. I can’t say that there’s an actual famine. Although, for the past few days, there have been some disruptions again, but the food is being delivered, more or less. It’s just that the prices have skyrocketed because it’s very expensive to deliver stuff here. They have to pay several thousand dollars for every vehicle. Then suddenly something new arrives in the shops and we find out that the Russian peacekeepers are responsible for the delivery. They’re allowed to cross over, the “ecologists” let them through. So [the Russian peacekeepers] deliver food here in their cars. You know, those white trucks. Humanitarian aid? They probably do give out something for free as humanitarian aid, but most of it goes to the shops. Ask any vendor why it’s so expensive, all of them will explain — because the peacekeepers ask for several thousand dollars for every vehicle.”

A grocery shop in Stepanakert. Photo: Ani Balayan

“From time to time, medication gets delivered too, by the Red Cross. But no one brings adult diapers, for example. They say it’s because they take up too much space, that’s what I was told in several pharmacies.”

“There’s no chicken meat at all, but other meat is available to buy, because it’s local, only that it has become more expensive, one kilo costs 4,400 drams (about 900 rubles, or €11 — author’s note). People have to get animal feed delivered and everything, so meat is getting more expensive with every day. Now, spring has come, people need to start up on their field work, but the Azerbaijani soldiers won’t let them do that, they shoot at the tractors from their checkpoints.”

People queueing up for food handed out under the ticket system. Photo: Ani Balayan

“We have a ticket system for basic necessities. Butter, rice, grains, eggs — there’s enough for everyone with tickets. Vegetables and fruit can be bought for normal prices if you have a ticket, but everything else is very expensive. Unaffordable with our paychecks.”

“The city has been significantly damaged, many people had to close down their businesses. I can’t even describe it. Everything around us is closing down. There’s only a few shops left.”

A shop in Stepanakert. Photo: Ani Balayan

“After the death of police officers (on 5 March, a car of the unrecognised republic’s police department was shot at, three police officers were killed — editor’s note), we went to the Russian peacekeeper contingent, we wanted to express our protest against everything going on. There’s a lot of blame on our locals too when it comes to the police officers’ death — if you are driving on a military road, you have to be more careful. That’s what I think. But at the same time, the peacekeepers are there exactly so things like that don’t happen. Why even have them at all then? The Russian peacekeepers have this slogan: ‘With us, there’s peace’. So we asked them: with you, there’s peace, are you for real? One of them came out and started butting heads with our boys. But they only talked to each other in loud voices, and that was the end of it. How Russia could be treating us like this, I don’t know. “

“What’s the thing I miss the most? Freedom. You know, if you’re able to get through to us… Can you bring me some tea? Just a simple pack of tea, regular tea…”

The police car that was attacked from the side of Azerbaijan. Photo: Telegram

Ecologists

“According to the trilateral agreement, this road is a humanitarian corridor to connect Armenia with Armenian residents of Karabakh,” this is how Azerbaijani political analyst Ilhar Velidaze explains the recent protests in the Lachin corridor. “However, we are able to follow the cargo movement through satellites and we have observed several times that the road is used for military cargo too, as well as soldiers coming in from Armenia. We couldn’t just act indifferently. Furthermore, armed groups that Armenia claims are the Nagorno-Karabakh defence army are operating on the territory of Azerbaijan. Did anyone even recognise this ‘army’? Finally, Azerbaijan’s natural deposits are being exploited on the territory of Karabakh inhabited by Armenians. These are polymetallic and copper deposits, and the ores were transported through that road illegally, seeing as this is internationally recognised territory of Azerbaijan and any economic activity can only be carried out here after alerting Azerbaijan. All of these issues led to tighter controls over the road.”

However, the Lachin corridor is being blocked by people who call themselves “ecologists”. Ilhar Velidaze only recalls this fact after I ask him about how any of it is connected to protecting the environment.

A Russian peacekeeper and an Azerbaijani “ecologist” demonstrating the gesture of Turkish nationalist organisation Grey Wolves. The Lachin corridor, December 2022. Photo: Telegram

“There was a preliminary agreement with Armenia that representatives of Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Ecology would be monitoring the territory of Karabakh where these deposits are developed,” he says. “The group arrived with the help of Russian peacekeepers. But the local ‘authorities’, I’m putting this word in quotation marks, interfered with [their work]. We just wanted to determine the damage caused to the environment. Forestlands were destroyed there, there were incidents with pollution of water resources, etc. But the local ‘authorities’ opposed this — and here came the ecologists’ campaign.”

During the four months of the “ecologists’ campaign”, several studies were published in Armenia, the authors of which claim that the activists in the Lachin corridor don’t have very much to do with the environment.

Former Ombudsman of Armenia Arman Tatoyan, founder of Centre for Law and Justice, published a report, which, according to him, proves that the pseudo-ecologists “never had anything to do with environmental issues and… are pursuing political objectives”. Having studied the activists’ social media pages, the Tatoyan foundation concluded that the road was blocked by “former servicemen” and “people who spread the ideas of the terrorist organisation Grey Wolves”.

“The claim that these people aren’t ecologists isn’t backed up by any facts,” Ilhar Velizade opposes. “Onsite studies could be carried out by any group that has come here to examine the situation.”

Arman Tatoyan. Photo: Facebook

He doesn’t consider the result of the “ecologists’” actions a humanitarian catastrophe. He also proposes to put the word “blockade” in quotation marks too.

“Unfortunately, the Armenian side is trying to misrepresent the situation as a humanitarian catastrophe,” he notes. “But there’s no catastrophe to speak of. Take a look at the so-called ‘blockade’, I’m putting this word in quotation marks. During the last three months of the Azerbaijani activists’ protest, the Lachin road was used by over 4,000 vehicles that were transporting various cargo, furthermore, these are heavy-duty vehicles. Can this be called a blockade?”

The Lachin corridor. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

Stepanakert. Nara

“I have three children, the oldest will turn ten in May, the middle one is four, and the youngest has just turned three,” Nara says. “My oldest is ill and is always on medication. He’s been suffering from cystic fibrosis and epilepsy since he was a kid. He needs to stay on a diet, he needs to be constantly eating green apples, but here, all the apples disappeared. While they were still being sold, I was shocked by the prices. In Yerevan, apples cost 150 drams, here they were 3,000.”

“Also, we’re only being delivered foods that the people always buy, while something additional, that my child needs, does not get transported here. Things have become a little bit better now; in January, there was nothing in the shops. But in January, many here were saying that they wouldn’t be leaving. Now, those who have children want to leave, because there’s no work here anymore. As for me, I’m a lawyer by trade, but there’s no work for me in Artsakh, so I’m studying to become a social worker.”

A market in Stepanakert. Photo: Ani Balayan

“Several days after the start of the blockade, we ran out of medication for my son, then it disappeared entirely — I couldn’t find it in pharmacies. I decided to take my son to Yerevan for treatment. But I was told it’s impossible to leave.”

“Many pass through, despite the blockade, but not for free. This is how my acquaintances went to Yerevan and back, through the Russian peacekeepers. I’ve heard different prices, up to $1,000 per person.”

A market in Stepanakert. Photo: Ani Balayan

“I got help from our former [State] Minister [of Nagorno-Karabakh] Ruben Vardanyan. After I met with him, I received a phone call from the Health Ministry and was told to prepare documents needed for my son to go to Yerevan. On the evening of 8 February, I got a phone call and was told that tomorrow we would be leaving in a Red Cross car. On 9 February, we were able to leave and stayed in Yerevan for a month. My son got treatment. Then I got a phone call from his school, they told me that if he didn’t go back he would have to retake the school year. I called the Ministry of Health and said that I want to go back because my son needs to go back to school. And we went back, also with the Red Cross. But in a month, we’ll have to go to Yerevan again.”

“One of the medications my son needs is very expensive, and he needs 12 pills a day. The government is currently providing us with it for free. The rest, we buy ourselves. I stocked up for the month we’d stay here back in Yerevan. When it runs out, we’ll have to go again.”

“It’s hard when the power gets turned off. And that happens constantly, every two hours for an hour. They say that moving forward, they will be turning it off every hour. It’s good that they turned the gas back on, at least we have hot water in the house.”

“No supply of medicine”. A sign raising awareness about the situation in Artsakh. Yerevan. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

Mines

Head of the Conflictology Department of Azerbaijan’s Institute of World and Democracy Arif Yunusov agrees that the “ecologists’” campaign is connected to the two mines that de jure became property of Azerbaijan after the 2020 war but de facto are developed by Karabakh’s Armenians. But the conflictologist has his own explanation of what’s happening on both sides of the Lachin corridor.

Arif Yunusov. Photo: Facebook

“Because of these two mines where copper and molybdenum are extracted there was a conflict between Azerbaijan and Russia,” he says. “There’s this company, Anglo Asian Mining Company, some of its shares are owned by daughters of Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev. Back in 1997, Azerbaijan granted [the company] the right of development of all deposits of gold, copper, and molybdenum in the country. But the two mines in question were on the territory controlled by Armenia for 25 years, and at that time their development was carried out by a formally Armenian company, however, its actual owner is a Russian billionaire. After the war, when Azerbaijan got Karabakh back, Ilham Aliyev raised the issue with this Russian company: for quarter of a century, you were extracting our non-ferrous metals, time to strike a deal. It seems they did come to an agreement because Azerbaijan was planning to plead the case in front of an internal court, but there was no case after all. In July of last year, Azerbaijan signed a contract with Anglo Asian Mining Company that included these two mines too, receiving $3 billion in return.”

If Arif Yunusov is to be believed, then

the Anglo Asian Company miners who had paid $3 billion were unable to begin the development of those mines, seeing as de facto the territory is controlled by the Russian peacekeepers. They needed Russia’s consent,

and Russia, it seems, was ready to come to an agreement with Azerbaijan.

Residents of Karabakh heading towards a blockpost with Russian peacekeepers for another attempt at negotiations. Stepanakert, December 2022. Photo: Ani Balayan

“Putin sent Ruben Vardanyan to Karabakh as his representative,” Arif Yunusov continues. “He was conducting secret talks about these mines, but they fell through. But for Putin, the main thing wasn’t the mines. Russia, dissatisfied with Pashinyan, assumed that Vardanyan would gain power in Karabakh, the next step being his candidacy as Armenian Prime Minister. Because as of now, no matter what protests are taking place in Yerevan, at least 60% of Armenians are still backing Pashinyan. Russia needed a new leader of the Armenian opposition, not connected to the ‘previous ones’. And he did become a notorious figure in Armenia. You may recall how Presidents [Robert] Kocharyan and [Serzh] Sargsyan came into power, they’re from Karabakh too. Karabakh is a jumping off point.”

This is Arif Yunusov’s version of events, but it has a right to exist. In Yerevan, I was explained by every second person I talked to — not all Armenians are pro-Pashinyan, but the majority of them hate his predecessors with their entire being, and it’s these former politicians who now make up the Armenian opposition.

Ruben Vardanyan, Russian billionaire of Armenian origin, came back to Armenia in September of last year, went to Karabakh, and was appointed State Minister. After the start of the blockade, he visited Karabakh’s villages, promised to punish vendors for high prices, and in general became a popular man in Stepanakert.

“All the moves made by Vardanyan in Karabakh in these three months were the correct ones,” journalist Naira Arutyunyan admits. “Negative reactions to his work came from three centres: Baku, Moscow, and Yerevan’s government.”

Perhaps, Ruben Vardanyan wasn’t Putin’s messenger. Perhaps, he was one but suddenly decided to start caring about the interests of Karabakh’s Armenians. Or perhaps, the entire thing was about the negotiations about the mines. In February, it came out that Vardanyan was dismissed from his position, as per the condition put forward by Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev. That was soon after the UN International Court of Justice demanded the Lachin corridor be unblocked. But the “ecologists’” pickets remained.

“We’re no longer talking about eco-activists,” Arif Yunusov clarifies.

“Now, Baku sends students there. If you have [failed in some class], you are asked: want to get a good grade? And so you get on the bus.”

“You stand in the cold for a bit, yell something — that’s it.”

When the condition of Vardanyan’s dismissal was fulfilled, Azerbaijan brought forward another one — this one has as much to do with the environment and ecologists (nothing).

“Now, they’re demanding there be a checkpoint built on that road because the Armenians are allegedly transporting weapons into Karabakh,” Arif Yunusov says. “Azerbaijan is suffering a big reputation loss; furthermore, the blockade makes no sense at all, the Russian peacekeepers deliver everything needed to Karabakh. It’s time for [Azerbaijan] to lift the blockade, but they’re being stubborn and continuing with it. Meanwhile, Russia is not agreeing to a checkpoint being built.”

Naira Arutyunyan. Photo: Facebook

Yerevan. Naira Arutyunyan

“My mum is still in Stepanakert,” Naira says. “She’s 92, she has stage 4 cancer; over the past year, she’s barely been out of bed, she had to use diapers. But seeing as there’s no more diapers in Stepanakert due to the blockade, mum has started getting up again.”

“Before, I would constantly visit my mum, to take care of her. My daughter-in-law and I would take shifts — one month I would be with mum, and then she would come in. Mum has an open wound that needs to constantly be treated. When the blockade started, I couldn’t go to take my daughter-in-law’s place. I mean, I could, of course, go to Goris where the Russian peacekeepers base is located. You have to stay there for about two weeks and plead your case, make a deal with them. Yes, all of this takes about two weeks. There are channels one has to go through to make a deal with the peacekeepers, so they transport you to Stepanakert, there’s a tax. All of this is, of course, unofficial. The only official way is to file a request to the Red Cross, and if there’s a real pressing need to go, they take you.”

“In Goris, there’s a live queue of people who arrived to make a deal with the peacekeepers to be taken [to Stepanakert]. I know someone who spent a month there waiting for his turn.

While you’re waiting for the unofficial authorisation from the peacekeepers, you have to stay in a hotel. But if you have a Karabakh registration, then you can stay there for free, the Armenian government allocated money for that. I could go to mum this way, but I’m scared that I won’t be able to go back. My job needs me to have a good connection, but in Karabakh the power gets turned off ten times per day. If I stop working, we won’t be able to make ends meet.”

We hired a sitter for mum, I pay her. I transfer the money to my niece’s bank card, she tries to withdraw it from a cash machine. The cash is also delivered to Karabakh in trucks by the peacekeepers, but there’s never enough money in the cash machines. You have to run around, find out which one has any. Furthermore, a cash machine doesn’t allow withdrawal of more than 20,000 drams. I send my niece 50,000 drams, while she asks me for 40,000, so she would have to go two times and not three.”

“The food is allocated through tickets, but you have to stay in a line to get them. My daughter-in-law is of age, so it’s hard for her to stand. When I send her money, she can at least buy something in the shop nearby.”

“The gas flows to Karabakh through the territory that has been under the control of Azerbaijan since 2020.

Early last year, Azerbaijan cut off gas for the first time. I was with my mum at that time. That was the worst winter out of all that I remember.

The snow was waist-deep. And during the coldest period, the gas got turned off. There, you need gas for heating and hot water. At first, we were confused and didn’t know what to do at all. Then we began to search for stoves in attics and garages. Now, people’ve got wood stoves in their flats, one thing Karabakh has plenty of is wood, for heating.”

The Red Cross supplying medicine and medical aid. Photo: Twitter

“Medication is delivered to Karabakh by the Red Cross. There’s a rehabilitation centre in Stepanakert founded and financed by a British baroness. It immediately turned into a centre of allocating aid. Everyone who needs medicine non-stop was registered there, they also helped people with chronic diseases. At first, the centre had its own medication reserves, but they all were spent. Then the Red Cross started helping with getting medicine. My mum, for example, gets delivered bandages and cotton wool. Unfortunately, they don’t have diapers.”

Margarita Karamyan. Photo courtesy of Margarita

Stepanakert. Margarita Karamyan

“I spent my entire life in Hadrut, four generations of my relatives are buried there,” Margarita tells me. “I left the town in the early hours of 8 October 2020. Two days later, Hadrut was taken; 23 people were still there, all of them were killed.”

“I remember the blockade of 1988, it was much worse. We have trade now, the Russian peacekeepers make a deal with someone in Karabakh and bring products in their vehicles. They bring it in as if it were humanitarian aid. A part is, indeed, shared for free but another part is sold in the shops. Half of it is sold to those with tickets, the rest for prices four times more expensive than in Yerevan. Especially vegetables and fruit. That is done basically in the open, everyone knows about this in Stepanakert. Because if you were to ask in the shop why everything’s so expensive, why before tomatoes cost 1,200 drams and now 4,000, you will be straight up told — because we paid one million so that the peacekeepers would transport our cargo in their white vehicles.”

“Then there were reports that they can transport people for 150,000 drams per person. It’s a well-oiled business. You have to either go to the base in Goris or to Khojali. And people are scared that this channel will be closed down too.”

“After the war, my daughter and I stayed in Yerevan because we found jobs here. But half of my family is currently in Stepanakert. My husband has a job here and my son has a business. He founded it back in Hadrut, then in Stepanakert he and his wife took out a loan and built a greenhouse. Last year, they were preparing to sow seeds but then the blockade started. The gas and power were turned off in Karabakh, it was impossible to heat the greenhouse. They sold everything they had grown to be able to cover their debts, barely. Now, they’re considering what they can sow that doesn’t need to be heated at least in spring. But they need to get the chemicals, fertilisers, and the rest from somewhere. They got lucky that my son had bought seeds before the corridor was closed. They live off my husband and daughter-in-law’s paychecks, she was able to get a job in an art school. That’s life — when you try your best time and time again, but still end up with nothing.”

A checkpoint on the border of Armenia and Karabakh. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]