5 March 2023 marked 70 years since the death of Joseph Stalin, the man whose rule Soviet citizens remember, on the one hand, for the victory in the Great Patriotic War and, on the other, for the millions of victims of the Great Purge, devastating collectivisation, and mass starvation.

The figure of Stalin had been present in modern Russian politics for a while: there were talks of depicting him on a mosaic in the newly-built cathedral of the Ministry of Defence as well as efforts to ban the distribution of a comedy film about his death. But after Russia began its full-scale war against Ukraine, the pace of re-Stalinisation seems to have accelerated. This February, for instance, was memorable not only for the transient renaming of Volgograd into Stalingrad, but also for the installation of a new monument to “The Leader”.

Novaya-Europe correspondent Ira Purysova spoke to Andrea Graziosi, Italian historian and expert on Stalinism, about why Vladimir Putin needs the figure of Stalin and Stalinist practices, what they have to do with Ukraine, and how life under dictatorship has affected Soviet and Russian society.

Andrea Graziosi is an Italian historian and Sovietologist, professor of Modern History at Università di Napoli Federico II, and fellow at Harvard’s Ukrainian Research Institute and Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies. In 2006, he was awarded the Ukrainian Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise for his research on the Holodomor famine and efforts to attract international attention to the subject. He is the author of “A New, Peculiar State: Explorations in Soviet History, 1917-1937” (2000), “Stalinism, collectivization and the Great Famine” (2009), “History of the USSR” (2011), and other works.

The fake that came true

In early February, a monument to Joseph Stalin was opened in Volgograd, and the city was renamed Stalingrad for a day (the latter, however, is common practice nowadays). Can we say that the war in Ukraine has actualised the figure of Stalin, or has this been going on before but we’ve only now noticed it?

Of course, the war has given everything new strength, even to phenomena that already existed. And naturally, the idea of Stalingrad and the victory in World War II have been given new importance. I think Putin’s relationship to Stalin is a conflicted one. We know that among his heroes are [writer] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Anton Denikin, the head of the Russian nationalist White Army — and both these figures hated Stalin. However, Stalinism has deep roots in modern Russia. Already in 1995, under Boris Yeltsin, 7 November, the day of the October revolution, was legally linked to the military parade of 7 November 1941, where Soviet soldiers marched in front of Stalin before going to the front to fight the Germans near Moscow. I would also say that fear of [fear of a recurrence of mass purges — editor’s note], and at the same time admiration for Stalin was decisive in shaping the ideology of Putinism. Of course, there are also other elements within Putinism — like, for example, gangsterism — but this is a key element.

What do you think turned Russia back into the 20th century and made it closer to the Stalin era in spirit?

A crucial point was the reinterpretation of the 1990s. I spent much time in Russia at the time and I remember that the year 1991 used to be a national holiday for the Russian state — celebrating the liberation from the Soviet Union. The idea was that the collapse of the Soviet Union was actually a consensual “divorce”. Those who went to sign the Bialowieza Agreement said: look, we are not like Yugoslavia, we are having a civilised divorce.

And this is true. [The leaders of the Union republics] calmly admitted there was nothing else they could do with the Soviet Union. This was a realistic assessment: the USSR had failed economically and was impossible to reform. But even those who were at the time willing to say “Let’s kill the Soviet Union” in a way regretted it, because [at least some members of the new Russian elite] actually liked this idea of a huge space.

Then Putin came to power and formalised it when he said that “the collapse of the USSR was the biggest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”. Instead of admitting that it was a failed system where, for example, people had a much lower life expectancy than in Western states, he made out the collapse of the USSR to be a plot of the West.

So, Putin created a fake, and it became true because many people believed in it. And I think the reason why they believed it was not because of a few malign people who elaborated this tale, but because they wanted to believe in it.

The Soviet Union was a big failure, and nobody likes to see their past as a big failure.

Why didn’t the memory of Soviet hardship prevent this?

Everybody knew that life was very tough in the USSR. But since the Soviet Union was the other superpower, you could be proud not of the suffering, but of being a superpower. This Soviet greatness cost a lot of blood, including the blood spilled during World War II. And the cult of victory became the other important narrative of the 1990s: “We were humiliated, but our greatness remains. It’s in the war, it’s in our victories.” At the same time one cannot deny that the victory was the result of the heroic effort of many millions of soldiers, but also of Joseph Stalin, who led the country. The fact is that you cannot claim the victory of 1945 to be a cornerstone of your history and then say you don’t like Stalin unless you present the war not as the triumph of a great power but as the symbol of resistance to a vicious aggression, an interpretation that Vasily Grossman proved possible.

In the 1990s, the Russian authorities started using the interpretation of victory as a “Muscovite” triumph as a way of healing [the trauma of the collapse]. I would say that this healing turned out to be poisonous. The re-Stalinisation process was amplified by the imperial structure of the Soviet Union and also by the criminal elements that came to power in that decade. This is what produced this cluster of ideology that we are dealing with today.

A 7 October demonstration in the Moscow centre, 2021. Photo: Mikhail Svetlov / Getty Images

‘There were more letters defending people than denouncing them’

How has the creeping re-Stalinisation affected the spread of Soviet-era dictatorship practices in contemporary Russia? We see that people are once again writing denunciations, not only under police pressure but sometimes also voluntarily. The state is looking for spies and “foreign agents”. Severe censorship has been introduced and propaganda is very strong.

When discussing this, one must keep in mind the proportions. The number of denunciations during the Stalin era is not comparable to what we are told about Russia today. If we talk about the Great Terror, that’s about 2,000 people shot per day for 14 months. This is absolutely unthinkable in modern Russia.

Besides, the purges were not as based on denunciation letters as we tend to believe. People were forced to confess and denounce others both on public trial and in private. They were tortured to this intent. We also know that about 800,000 people killed during the Great Terror were shot on the basis of secret decrees by categories — something like quotas. If you had a Polish name, were of German origin, were a member of the Orthodox Church, were convicted for more than three years, had already passed through the Gulag in the past or were an anarchist, you could be shot. It was not only denunciations, but also a clean-up operation of enormous scale.

When I worked in the former Soviet archives, there were many more letters defending those who were arrested than those that denounced them.

They all read along the lines of “You have arrested my uncle, but he is a completely innocent man. Why have you done so?” Maybe there have been new archives discovered since then, but my very strong impression was that the role of denunciations has been exaggerated. Of much greater importance were the secret decrees that I invite everybody to read now that they have been made public — starting from the decree from July 1937 and then the decrees concerning the “Polish operation” and the “German operation”. This was what gave those numbers of casualties. Those who ended up in the first category were shot, the second category was sent to the camps.

All of this was done administratively. Let’s say I’m a local NKVD chief and receive an order to find in my city 5,000 people for the first category and 10,000 for the second category to be deported within the next two months. So, I make a list and realise that there are not enough names on it. I know that if I don’t get the necessary number, I will be next in line for sabotage. So, I start torturing people, extracting confessions out of them and demanding that they give me more names. After the torture, the person would include their aunts, uncles, friends on this list, writing that they are all British spies. This was the real mechanism of repression in 1937-38.

The search for “national traitors” has clearly intensified in Russia today. At the legislative level this is done, for example, through the status of “foreign agents” and “undesirable organisations”. At the level of rhetoric, it is manifested in Putin’s statements about “all this scum” that is allegedly trying to split society. In such an information field, it is difficult not to think of the Soviet era. How did the category of “enemy of the people” appear in the USSR and how did this categorisation work?

The “enemy of the people” category comes up in every war. During World War I, European countries had been gripped by a fear of enemy agents. Stalin was a Bolshevik, hence a man who waged war even in peacetime. Therefore, he saw traitors who were getting in the way of building socialism all over the place. From this point of view, the Soviet experience in Stalin’s era becomes a radicalised version of the common European experience during World War I. You have to mobilise to be victorious. In Stalin’s mind, victory meant socialism. The closer you are to socialism, the more dangerous the enemies, since they see that your victory is coming. So, the label “enemy of the people” was used as a propaganda tool. That is how they labelled people who were supposedly dangerous and needed to be destroyed.

Could people not have been aware of the repressions? If, for example, they did not fall under decree categories or were apolitical.

The vast majority knew of the repressions. You have to understand that not everybody who went to the Gulag stayed there. Many returned home. During a period of over 20 years (1930-1953), a total of about 35 million people, out of a population of 170 million, had experienced repression in some way. Many died, but a very significant percentage made it through the system.

I don’t think most people knew what you could be imprisoned for, because the contents of the secret decrees only became known much later. But it was also impossible not to know that this was happening.

How similar do you think this fear of sudden arrest is to what war-opposing activists in Russia or those listed as “foreign agents” now feel?

If I were in their place, I would be totally scared — that’s why I don’t believe the opinion polls. Of course, the situation is different now: people are unlikely to be suddenly taken away, tortured, and killed on such a mass scale. But the fear is the same. I think there were brief moments in the USSR when the population hoped for real improvements. In the first post-war years, around 1944 to 1946, for instance, there was this hope that the victory was going to bring on an open society. But with the famine and new arrests, these hopes went away, and there was a reign of fear until Stalin died. I always tell my students as an example of the scale of things that in a mere two weeks after Stalin died, the first million people were released from the camps because everybody knew this was untenable [this refers to the vast amnesty signed by Lavrentiy Beria on 27 March 1953, which freed 1,201,738 people — editor’s note].

Prisoners working on the construction of the White Sea Canal. Photo: Laski Diffusion / Getty Images

On the other hand, we see that in modern Russia there are no purges among the elites, as was the case in Stalin’s day. Why did the repression affect the elites then and not now?

I think this is explained by Putin’s megalomania. He rebuilt the Russian state and has been in power for 23 years now. Everybody that got a commanding position was appointed by him. Everybody owes him something. I think Putin feels that his hold on the Russian elite is very strong. Stalin could not be so sure of things in 1931-1934, because the elite surrounding him was the Leninist elite.

So, Putin is closer to a post-victory Stalin in 1945, resting assured that the elite will not revolt against him.

On the other hand, think of Mikhail Khodorkovsky. He was put in jail and kept there with no charges, and people know this. Since the beginning of his rule, Putin has used brutal violence very selectively. But I do believe that many in the top Russian elite would rather see Putin dead, the same fate many top Stalinists hoped for Stalin in 1952.

‘The Holodomor was a punishment for Ukrainians’

What was Stalin’s attitude towards Ukraine? Is it similar to Putin’s attitude?

There are similarities and differences. For the young Stalin, Russia was not a single nation, but more like Europe — a continent inhabited by many different people. This is very similar to what Putin now says about the “Russian world” — “many nations gathered around the great Russian people”.

And it’s very similar to the words on the banner: “I am Kalmyk, but today we are all Russians!”

Precisely. In 1932, the Soviet Ukrainians became the Ukrainians that Stalin did not want — he wanted “his own Ukrainians”. So, the idea was to recast them, turn them into “good” Ukrainians. To do this, Stalin not only caused the great Ukrainian famine, which killed millions [according to the Institute of Demography and Social Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the excess mortality in 1932-1934 was 3.9 million people — editor’s note], but also destroyed the entire Ukrainian communist and intellectual elite. Mykola Skrypnyk, a prominent Ukrainian party figure who was a personal friend of Stalin and opposed his policies in the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, committed suicide during this time.

Interestingly, in 1939, when Stalin initiated the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and invaded Poland, he used the same logic that is used today, calling the attack a “special military operation” and not a war, since the USSR was allegedly recovering Ukrainian territories. [Similar rhetoric was used in relation to Western Belarus and part of the Republic of Lithuania, whose lands were annexed to the USSR as a result of partition Poland — editor’s note]

Body of a woman starved to death. Poltava region of Ukraine, 1934. Photo: Daily Express / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Can we see any parallels here with the way Putin perceives Ukraine?

I think Putin sees the Belarusians and Ukrainians as local manifestations of the Russian people. They can only exist as separate groups if they behave well. If they behave badly, they should be punished. So, there is a certain similarity in Putin’s and Stalin’s attitude towards Ukraine, though it comes from a different context. In a sense, Putin is more of an original Russian nationalist, which can be seen in his close relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church. For the Russian Orthodox Church, the fact that Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians are one people is undeniable.

What distinguishes the Ukrainian famine of 1932-1933 from other famines in the USSR, and why does the Ukraine, as well as many other countries, consider it a genocide?

The more we study Soviet history, the more we learn about the famines plaguing it. We knew that after the Civil War there was a great famine in 1921-1922 which was caused by political factors as well as the weather. We knew there was a massive famine in the early 1930s and also after the end of World War II, in 1946-1947. We now know that there were at least five or six famines of a similar yet different nature in the early 1930s.

The first epicentre was in Kazakhstan. In 1931, many nomadic Kazakhs died of starvation because their herds were being taken away to provide meat rations for the army and the cities.

There was a terrible famine in the German Volga region, in the rural areas of Kuban and in the North Caucasus. Deported kulak peasants died of hunger in mass in 1931 and 1932.

The specificity of the Ukrainian famine is that it was a punishment. Kazakhstan suffered because the Soviet state needed meat, which was taken from the republic without much concern for what would happen to the people there.

A memorial to the victims of the Holodomor, Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: Oleg Pereverzev / NurPhoto / Getty Images

With regard to Ukraine, however, Stalin believed that it was necessary to break the Ukrainian peasantry and destroy the national-communist elite that had ruled Soviet Ukraine from 1922 to 1932.

And for this, the Holodomor was a suitable tool. This is why I think that the term “genocide” can be used, even though genocide is a legal category, so it is difficult to use for historians as it implies very clear criteria. But if you use that terminology, the famine in Kazakhstan was also genocide — it may have taken the lives of up to a third of the republic’s population, which put the Kazakh way of life on the brink of destruction.

In a sense, although on a much smaller scale, we now see a parallel with the “denazification” with which Putin justifies the war. At the start of the war, Putin expected that the Ukrainians would be happy that the Russians are coming. There would only be a few thousand “traitors”, “Nazis” — whatever you want to call them. They would be killed or forced to flee, and the rest of the Ukrainians would welcome the Russians and be happy. But the Ukrainians resisted, and suddenly it turned out that there were not thousands, but millions of “traitors”. At some point, it became impossible to discuss and after a brief discussion of how to mass re-educate millions of “traitors” the topic was basically dropped.

The next step was similar to Stalin’s methods, however, though at least not as bloody — for now. So you don’t want to be Russian? You don’t want to be with us? Then you will suffer and die in winter without heating and electricity, because we will bomb your energy infrastructure.

What role does the famine in Ukraine play in Russian historical policies and contemporary Russian society? The Russian state does not officially acknowledge that it was genocide.

The idea of recognising it as genocide was rejected at the official level back in the 1990s, although discussions were open then. I remember having very civilised arguments about it with my Russian colleagues. They did not deny that there was a famine, that millions died in Ukraine, but they always stressed that it was a Soviet-wide tragedy, that it was not specific to Ukraine, to Kazakhstan, to the Kuban region.

Of course, in a way this makes sense — everybody was suffering in the early 1930s. But Russian society refuses to see the specificity and peculiarity of these cases and the much bigger catastrophe —because it would have implied that the Ukrainians were somehow different.

The memory surrounding victory

In your opinion, why has the memory of repressions not become the basis for building a post-Soviet society? Even in school history classes, the Great Terror is usually glossed over.

For the most part this is because the period of the 1930s and 1940s has been superseded in Russian historiography and history teaching by the Great Patriotic War and the victory in it. This is not to say that the authorities do not recognise that the terror took place: there is a monument to the victims of political repression in the centre of Moscow; Putin himself supported the idea of its installation and, together with Dmitry Medvedev, attended Solzhenitsyn’s funeral in 2008. Putin’s rhetoric has the hallmarks of a wide range of ideologies, it is a hybrid, and hybrids can be very aggressive and dangerous.

There have been real battles for memory going on in Ukraine since 1991. A significant proportion of both historians and ordinary citizens believe that the Holodomor should be the cornerstone of Ukraine’s historical policy as a new state. In Russia, such the active battle for memory did not last long, because building memory around the victory in the war was the simplest and most obvious solution.

Back in the 1990s, I had a conversation with the now-deceased founder of “Memorial”, and he told me that one could have tried to base Russia’s historical policy on different periods and figures — for example, Peter the Great, Alexander Kerensky, or the Socialist Revolutionaries. However, this would not have caught on with the populace because the real legitimisation of Russia is unavoidably 1945.

How was Stalin’s dictatorship perceived in society?

The perception of Stalin by the society of his time must be divided into two stages: before the war and after. Before the war, Stalin was an extremely unpopular figure. There was even a secret decree forbidding him from walking in the city for fear of assassination attempts. He knew that he was also disliked even within the party, and that 80% of the population, meaning the peasantry, hated him because he had, in effect, imposed a new serfdom.

Victory in the war made him a leader in the eyes of a great many people, so the difference between before 1941 and after 1945 is serious. Of course, he was not accepted by the population of Western Ukraine, the modern Baltic states, and other forcibly annexed territories, and the “punished peoples”. But he earned popularity among the new imperial bureaucracy that he created. Imagine being a nobody from some Russian town and being appointed head of a Czech or Hungarian city. So Stalin became popular among the elites after World War II.

At the same time, the elites feared him. That is the only explanation as to why they decided to openly declare what a monster he was only in 1956, three years after his death [in 1956, Khrushchev made his report “On the Cult of Personality and its Consequences” to the 20th Congress of the CPSU — editor’s note], although they had begun discussing this fact immediately afterwards.

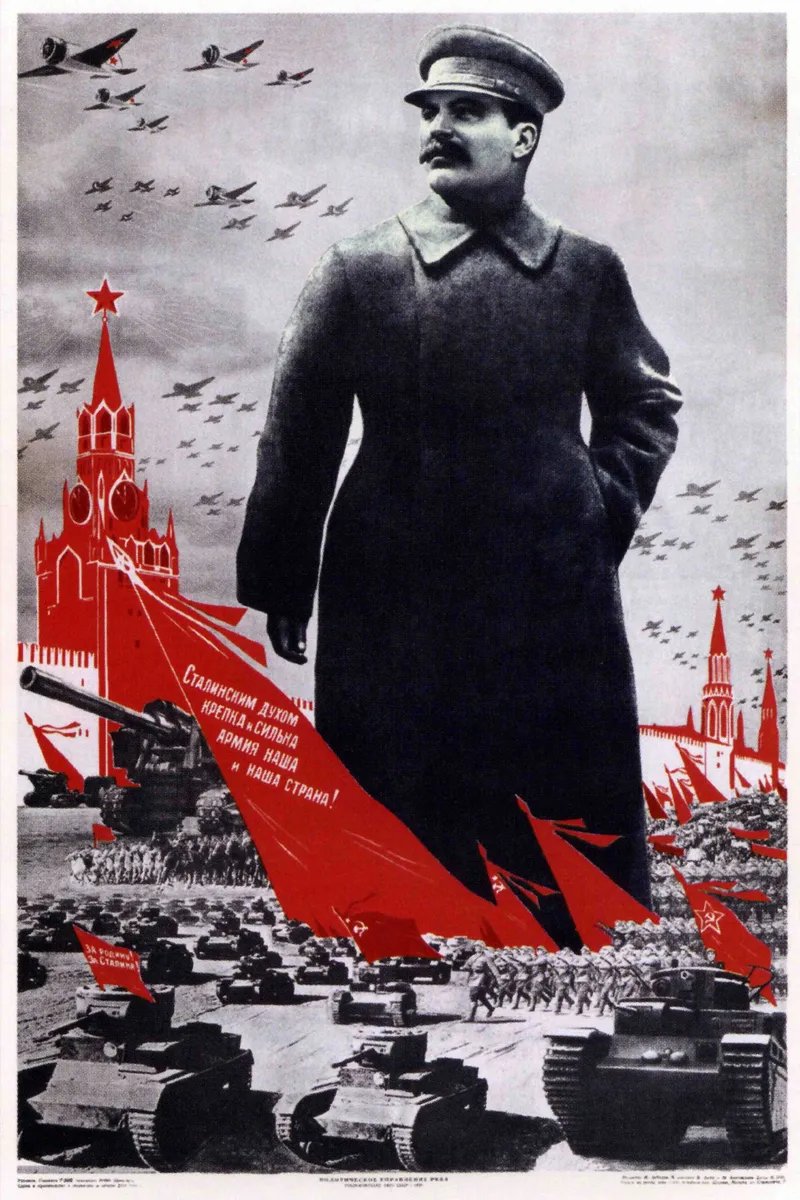

A 1940s Soviet poster. Photo: Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group / Getty Images

What effects of Stalin’s dictatorship could be seen in society after his death?

After Stalin’s death, society changed a lot. In a sense, the “good times” came. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, there was less repression, albeit no freedom — people continued to be imprisoned, including for dissent. But for fifteen or twenty years the Soviet people had hopes, which ended in 1968 with the invasion of Czechoslovakia. Later, in the 1970s and 1980s, the situation became much more complicated.

I would say that it was as if the USSR had lived two lives. One of them was very tough, horrible; the other had positive aspects, especially in comparison. Nowadays, people try not to look into the harder part. Memory is a political construct. It depends a lot on what surrounds you: where you get your education, what you watch on TV, what you read.

Do you think that the mechanisms of dictatorship that were used then can be effective in Putin’s Russia? I mean the methods, not the scale.

We can look for similarities between Stalin and Putin, but it is very difficult to answer this question. Like Stalin, Putin loves history, talks about it, writes articles about it. Both have chosen the West as their primary target. Both have made Russia the centre of their own world. But we are talking about different eras.

Putin has already used violence at liberty — remember what he did in Chechnya. What he is doing now in Ukraine is also terrible for Russia (I do not mention how terrible it is for Ukraine because this is obvious). And I think a lot of Russians know this is disastrous for Russia.

Stalin is now an important conflictual figure for Putin. He has repeatedly spoken positively about Solzhenitsyn and meetings with him. Putin must therefore be aware that Stalin destroyed the Russian peasantry, the Russian Orthodox Church, Russian culture and the Russian intelligentsia. However, what is more important to Putin today is that Stalin represents the “Russian world” and the rebirth of an empire.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]