Last Tuesday, 1 November 2022, marked 40 days since the death of Oleg Gradusov — a volunteer-soldier from Gatchina (Saint Petersburg region) who enlisted to fight in Ukraine. He had fought in the Second Chechen War, and had said many times before that he’d seen enough war for one lifetime. But all the same, he left for the front — only to return home inside a zinc coffin.

I happen to have known Oleg personally. He was born in Komi, but he had lived in Gatchina for as long as he could remember. During his military service (1998–2000) he took part in an anti-terrorist operation in Dagestan and Chechnya. He didn’t like talking about it.

“Dirt and blood — there’s nothing romantic about that,” he once grunted, in response to hearing someone praise a war movie. “Better to watch ‘Schindler’s List’ if you’re looking for a war movie. Now that’s real war.”

In school, Gradusov was interested in the history of World War II. He took part in school history competitions, always taking first place. He could tell you anything about any battle of that war. But after his military service, his interest towards history disappeared. He completed technical college, and got a job at a car dealership.

“He was really great with cars,” his former colleague Igor Kovalev told Novaya Gazeta Europe. “His thing was foreign brands. He just understood them. Especially if there weren’t any original parts and replacements were needed. He was an expert. In 2017 he opened his own car shop, things were good. He planned to grow the business.”

After February 2022, foreign manufacturers left the Russian market, and Oleg’s client base shrunk. Spare parts became rare. For some time, he could still operate his shop, but by June he had to close it — he had no money to pay building rent. Even after selling his equipment, he barely had enough to pay off half of his loans.

Oleg Gradusov. Photo from family archive

“Oleg had a five-year-old son from a previous marriage, who was born on 9 May,” his wife Irina told Novaya Gazeta Europe. “When we celebrated his birthday this year, he asked his father: ‘Are you going to war, Dad?’ Oleg then answered ‘There’s no war here, and it’s a good thing we don’t have it.’ But I could see that this idea stuck with him.”

Novaya Gazeta Europe already wrote that volunteer battalions, or, according to some reports, regiments, are being organized in Saint Petersburg region. In the summer there were two: “Ladozhskiy” and “Nevskiy,” and by autumn there was one more: “Leningradskiy”. These are artillery units, and they are incorporated into the regular Russian army. But they are partially funded by the region’s governor. It was in this regiment that Gradusov enlisted. Oleg admitted to Novaya Gazeta Europe three days before leaving for Belgorod region that he did not want to sign a contract with the military, but he did not see any other option.

“After I had to close my shop, I’ve been looking everywhere for work,” said Gradusov. “Everywhere you go, the salaries are 25–35 thousand rubles [€400–€570] and there’s a ton of unemployed. They pay more in Saint Petersburg, but you just can’t commute that far each day. When I went to the recruiter to learn more about these volunteer battalions, I was pleased it was for the artillery unit. As soon as they saw my military specialty, they almost forced me to sign a fixed contract. But it’s probably best that I go, instead of them sending some ‘green’ guys, who’ve only ever seen assault rifles in pictures. I had seen enough of them during Chechnya…”

The speciality Gradusov had was the most sought-after: sniper.

They convinced him to sign a contract with the motorised rifle unit instead of the artillery unit. They promised his load-out would be the very best. Moreover, Gradusov would be a sergeant, not a private.

The minimum salary would be in the 350-thousand-ruble (€5,700) range. Only Gradusov would never get it. He was killed only four days after joining up with the unit.

On the night of 23 September, the unit Gradusov served with relocated to new positions. Near the village of Svatove (Kharkiv region) they fell into an ambush. The column was intercepted in a pincer manoeuvre and shot at by tanks. A participant from the battle attended a memorial service marking 40 days after Oleg’s death. Novaya Gazeta Europe was able to speak with him.

“They shelled us from German-made tanks,” said participant Alexey S., “After the first wave, many panicked, but Oleg kicked guys off the BMP [infantry fighting vehicle]. He knew that at night, tanks shoot at the biggest targets, so he pulled everyone off from the vehicle. He couldn’t get away himself. He was killed from shrapnel from a shell.”

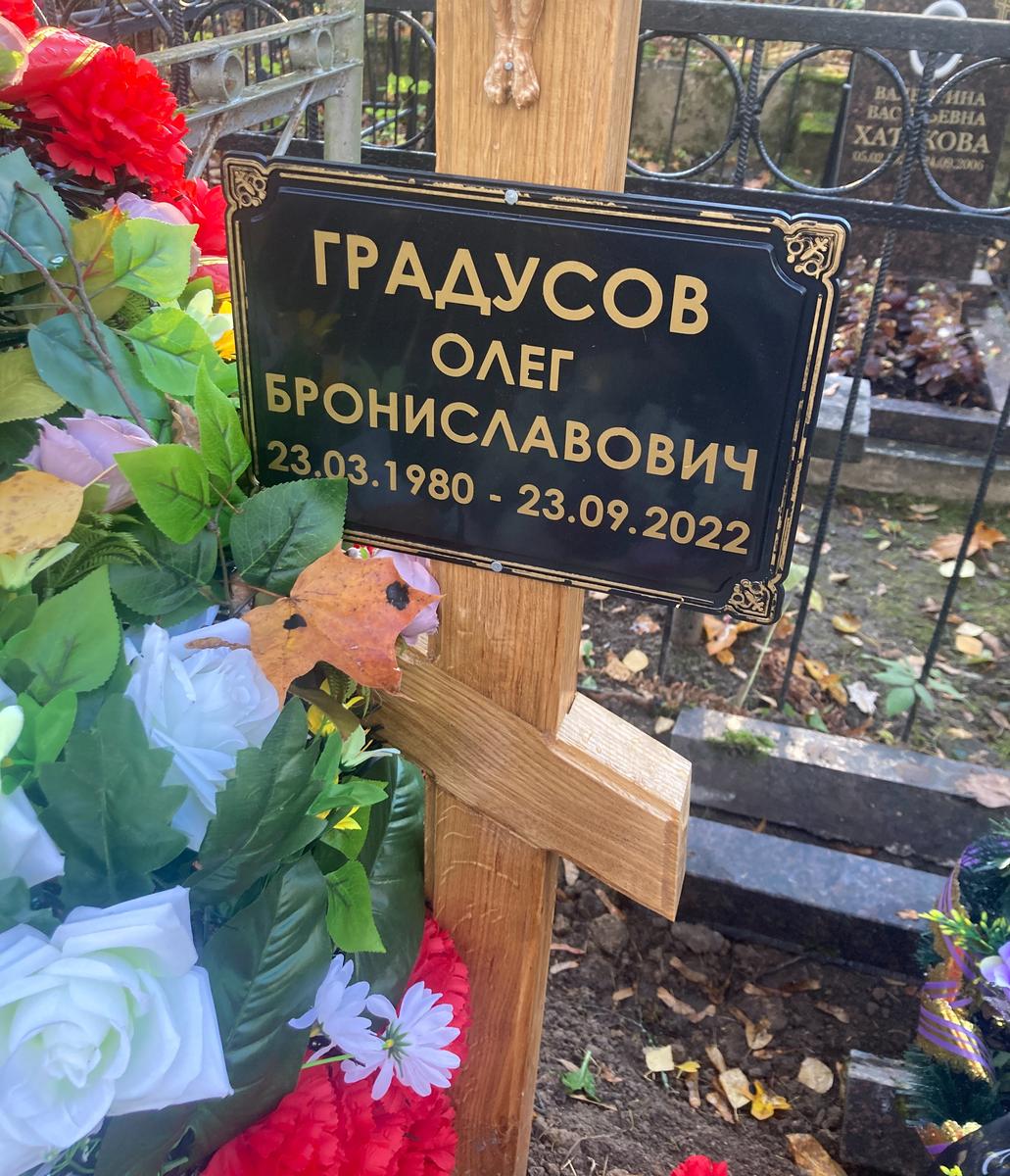

Grave of Oleg Gradusov. Photo: Oleg Leonov

In the words of Alexey, all the soldiers were wearing body armour. But these were ratniki (translator’s note: an older model of body armour) made in 1954. The plates only covered the chest and back. He was struck by shrapnel in the left armpit.

“We just arrived in Ukraine, and encountered the ‘privateers’,” said another military colleague of Oleg. “That’s what we call the soldiers from PMCs (private military companies). Look, they were equipped mostly in armour plates made of either kevlar or ceramic. Not only do they weigh less, but they also cover almost your whole torso. Oleg wanted to buy them. But our commander told us we can’t wear them. We’re not supposed to according to orders.”

***

In 2005, I covered the trial of Anatoly Litmanovich and Igor Borisov, the technical and commercial directors of Luga Abrasive Plant (LAP). They were suspected of smuggling double-use contraband products. As it follows from prosecution materials, in 2000, LAP received an order from Israel to cut out complex ceramic designs. Only LAP could have cut them out, and the technology itself was invented by Litmanovich. These parts were intended for the manufacturing of body armour.

“I was offered to move to Israel back in 1997,” Litmanovich said to a journalist in 2004. “They offered an irrevocable option of one million dollars. Only if I shared the technology. I can cut anything out of any durable ceramics, and they cannot. But what would I do there? Here, I’ve got my dacha [translator’s note: summer cottage], fishing…”

The Moscow Court of Saint Petersburg acquitted Litmanovich and Borisov. But the very fact that in 2000, Russia had the technology to manufacture body armour to cover almost the whole body begs the question: why was this not developed, and why was there no research in this field?

However, it’s completely possible that research was carried out, but this remains a secret. But again, the question: how come our army continues to use old models of body armour?

“Those who have served in the army no longer laugh at the circus,” Yevgeny Muravyev, third-rank captain in reserve, told Novaya Gazeta Europe. “You won’t believe it, but when I served at the Northern Fleet HQ, I found an order from 1922, which instructed an officer to leave their horse after he’s discharged. And this order was still valid! No one ever bothered to cancel it. It’s basically the same with personal protective equipment (PPE). To cancel old orders and instructions, you need to go through so much paperwork that you just want to scream. Of course, after the 50s, and especially the 80s (when our “armour” got war experience in Afghanistan), a lot of new research began. But the old instructions firmly state: PPE “ratnik” must be equipped with body armour 6B45, full stop. Someone’s too lazy to sign a few papers, and because of this our guys will die.”

Support independent journalism

However, there is another point of view on why the army does not have modern body armour. An employee of a private security company (PSC), who wished to remain anonymous, told Novaya Gazeta Europe that newly designed body armour is sent to the army. But then they are resold to private entities (such as PMCs or PSCs).

“Our firm has 16 pairs of body armour, 10 of which were made in Russia,” said the private security contractor. “And they’re great quality. We bought them offhand from a warehouse manager. We could have bought them straight from the factory, but to buy a batch of 10 from there would not have been cost-effective. So, they manufactured a thousand and ten by order of the Ministry of Defence, but this “armour” just fell into disrepair in these warehouses, and it was written off somewhere. And now they dress the guys in what they have on hand.”

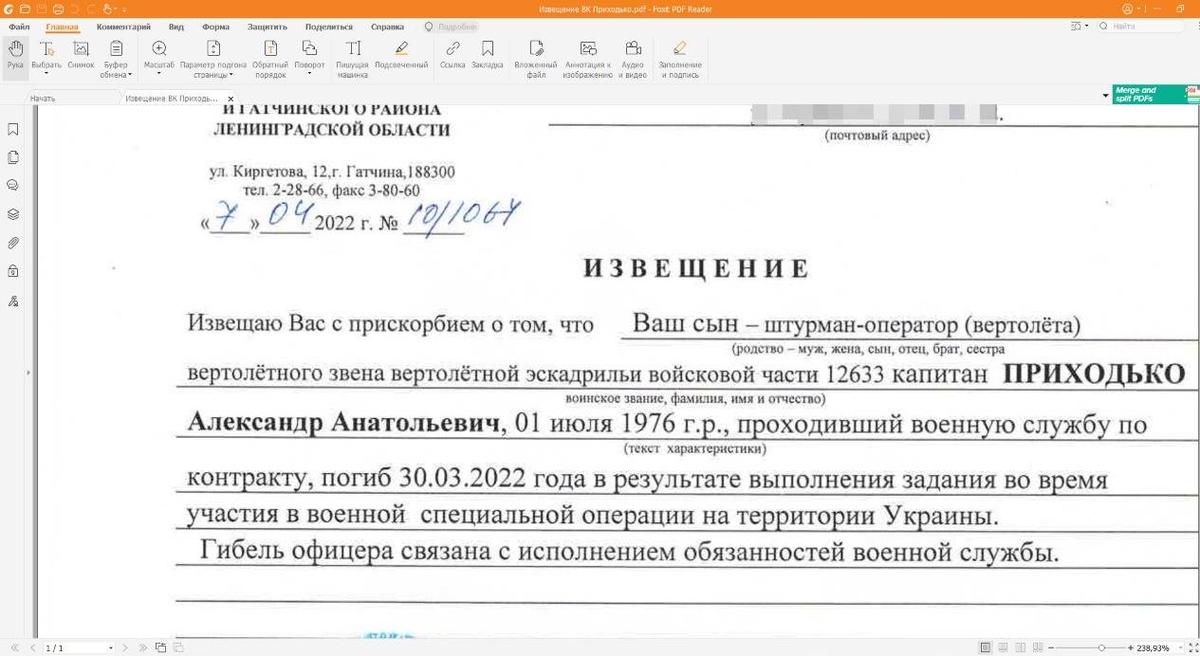

Oleg Gradusov became the second resident of Gatchina to return home in a zinc coffin. The first was captain Alexander Prikhodko, helicopter navigator, who was killed in Ukraine on 30 March 2022. Last week it was reported there would be another funeral. This time for a mobilised soldier. But so far, the enlistment office has not confirmed it.

‘We deeply regret to inform you that your son, a helicopter operator at Military Unit 12633, Captain Prikhodko Alexander, born 1 July 1976, who was undergoing contract service, was killed on 30 March 2022 while fulfilling an objective during his participation in the special military operation in Ukraine. The officer died doing his military duty.’

Death notice of captain Alexander Prikhodko, received by relatives

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]