“We thought about closing the place temporarily right after the strike,” says a waitress at one of Kherson’s cafés. “It was really scary. But suddenly crowds of people started coming, forming a long queue. I think they were so stressed that couldn’t make it without a good coffee and a bite of something sweet. We didn’t have a single minute of rest for several hours, which was very surprising since the price of coffee went up badly when the war began, so we started losing clients.”

A courthouse where Russia’s occupying administration is seated, was targeted by several Ukrainian missiles on 16 September. Usually, the entrance to the courthouse is a crowded place early on weekdays as locals often come here to try and learn something about the fate of their relatives kidnapped by Russian soldiers. Normally the crowd vanishes at around noon after receiving no intelligible response.

Kherson Photo: Getty Images

“It was about 11 a.m.,” says Daria D., a local resident. “I was in a car with my husband and my daughter about 3 miles or so away from the city centre. We heard horrible explosions; those were so loud as if they went off right above our heads. Stremousov (a major occupation official — translator’s note) says there were five HIMARS missiles, but I heard only two or three.”

Daria then headed for the city centre to see what had happened. It appeared to her that the missiles hit the rear side of the building, and not the façade. The building was damaged, but it did not seem as half of it collapsed like Russia’s media claim. There were roof timbers all over the place, some 100 or more feet away, and there were metallic shards in the park across the street. The pedestrian zone which Russia’s soldiers barricaded with Czech hedgehogs when they captured the city is now covered with bricks and other debris. The windows of the neighbouring residential building were smashed, but only those on the top floors.

“I don’t know if anyone was actually killed there,” Daria says. “Russia’s media say some people were wounded; Ukraine’s ones say nothing about that. I saw no dead bodies when I arrived, but I got there an hour after the explosion. Maybe the bodies had been taken away by that time, I’m not sure.”

Daria also says Ukraine’s army hit a school building where Russia’s troops were stationed for a long time;

now they moved to a dormitory in the heart of the city. Daria is certain that one should stay away from that building, too.

“I paid a visit to an elderly woman I’m acquainted with; she had a stroke recently and now she’s all alone in her apartment days on end,” Maryna, 60, says. “When I arrived, I heard the missiles hitting the area, I wasn’t sure what they targeted. Perhaps the Antonivka road bridge? The noise of the missile was different from what we’re used to, it had some whooshing sound in it. The ground was shaking, it was really frightening. Missiles often hit my neighbourhood, too, but that’s the outskirts of the city, and the sound is totally different. Ukraine targets its missiles at Russia’s positions, but Russians launch their rockets from my neighbourhood as well. I’m not certain where their rocket launcher is located but it surely is somewhere near my house, it strikes rockets all day long. I’m really afraid that Ukraine might hit this thing in response.

A supermarket in Kherson. Photo by Stringer/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Maryna says dairy products have become twice as expensive during the past week. Many farmers have not prepared enough hay for the winter as the fields are mined now. Therefore, there isn’t enough food for cows, so farmers kill them for meat, and there are very few milking cows now.

“I think it’s going to get even worse,” Maryna says. “We have food, but it’s way more expensive now. We also face problems with electricity supply and mobile coverage. This usually happens when either side delivers a missile strike. It seems as if Russians cut our electricity supply out, and that there are no actual damages to the power grid. All our electronics might go out of service eventually. What are they going to steal from us then?”

Ivan, a local businessman, says he was in a state of shock three weeks ago when all the local people spoke of was the potential Ukrainian counteroffensive. The general narrative was something like “look out, ‘Ruscists’, here we come!” Ukraine has bombed all the local bridges, so moving around is out of the question.

When Ukraine recently launched their counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region instead, Kherson locals grew sad.

There has been no movement in the Kherson region for two weeks, but some action started to appear there in recent days.

“All sensible people realise that it is not going to be a quick counteroffensive, if we really want to help Ukraine’s army, we need to be patient,” Ivan says. “I don’t want to be with Russia, no. They showed us what kind of country they are: they kidnap people, and those rarely return. My business partner was kidnapped once, and he survived by a miracle. They tortured him with electricity, stabbed him, and deprived him of food, water, and access to the toilet. His only fault was that he wished to live in Ukraine. They wanted to break his will. Sometimes they torture people and force them to record videos, they force them to say on camera how much they love Russia, and they make them apologise for something. If you see a video like this, you should know that the person in it was certainly tortured.

My son is a schoolboy, but we didn’t sign him up for the Russian school, so he attends classes at his school online.

If he has any questions, my wife and I explain things to him, we’re qualified schoolteachers. Russia promises 10,000 rubles (€170) in payouts for each child, but this can only attract those who have never actually worked honestly and lived off handouts when Ukraine was still here. How many of them do you think there are in our city? Maybe 500 or 1,000 people, and that’s it. This number includes the old timers who dream of living in the Soviet Union again. Those are the ones that Russia’s TV uses for their propaganda.”

A shopping centre in Kherson. Photo: Stringer/Getty Images

Ivan and his wife are unemployed now, they live off what they had stocked earlier. When the war started, they bought flour, sugar, noodles, and cereals — a large sack of each commodity. The prices went up in March and are still more or less on this level. A kilo of lunch meat sells for 800 rubles (€14).

“My factory has been occupied by Russia’s servicemen since the war started,” a Kherson businessman says. “We stopped production, and we never show up at the location anymore. When we last did, they threatened shooting us dead and kicked us out, holding us at gunpoint. I don’t know whether they looted our equipment or it is still there. Some Russian security man gave me a call recently and told me I should restart the production, otherwise I’ll have all my equipment confiscated. How am I supposed to restart it? I have no raw material, I have no fuel, and I have no workers. Well, perhaps I might be able to buy some commodities, but I’m not going to put my people’s lives at risk by forcing them to work at gunpoint. As for Ukraine’s missiles, I’m OK with it. We need to bear this discomfort and try to stay safe. How else is Ukraine supposed to liberate us? One must try to avoid locations where there are a lot of Russian troops, and that’s it.”

Halyna, a businesswoman from Hola Prystan, says the locals are normally in higher spirits than usual after Ukraine’s strikes. The collaborators, however, had grown sad after Ukraine started its counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region.

Those who have been staying low key in the past months now feel more cheerful.

“I have a small business here, and Russia demands that it be re-registered with Russia’s tax agency,” Halyna says. “I’m trying to play dumb and do nothing, of course. They did not issue any official notice, so I don’t care. If they come to see me in person, I’ll pretend to be happy to hear it from them. And then I’ll close the shop and wait for Ukraine to liberate us. Russia’s authorities are enemies to me. I do not tolerate violence. They’ve killed so many people, destroyed our infrastructure, and keep telling us that this was for the good of Ukraine.”

Halyna says Ukraine’s strikes are precise. When the local quayside was targeted, the nearby residential buildings remained intact. There was some minor damage from the metal parts flying around, but no houses were actually destroyed. The bridges were destroyed, however, but Halyna says that this is sad but acceptable. There’s a ferry line across the Dnipro River now, one-way ticket is 40 UAH (€1.1). It takes about an hour to cross the river, which is quite a long time actually. The same ferries were used 30 years ago.

“Some people are ready to endure this for the sake of potential freedom from Russia’s rule, others got used to it. Most of them receive handouts from Russia and keep saying that the most important thing is no fire,” Halyna says. “Our town is mostly elderly population these days. They’re happy to get Ukrainian retirement money to their debit card, and to receive Russia’s retirement money in cash at the same time. So, they see nothing wrong about it. Both are money. They say: ‘I’ll buy myself some lunch meat, and everything’s going to be fine.’ They say they want peace, and that’s it. There are also people, however, who are angry about what’s going on, they say: ‘Our children worked hard to build a house and buy the furniture, and now they’re forced to flee their home and abandon their belongings.’”

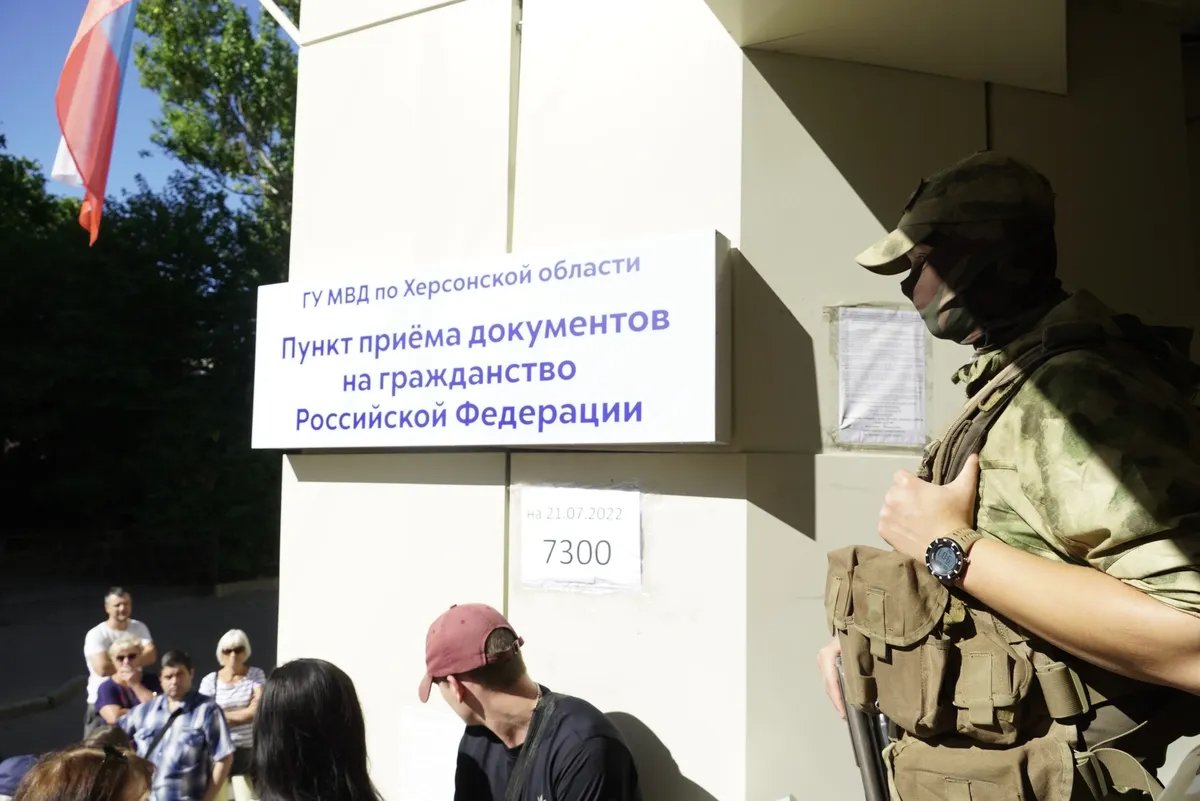

Kherson, Russia’s serviceman stands watch. Photo by EPA-EFE/SERGEI ILNITSKY

Nastia who lives in Stara Zburivka says she is tired of this war but hates Russian soldiers more and more each day. The so-called Kadyrovites arrived in their locality one day, picked the best house and told everyone they were going to live there, so they kept the doors intact. The house was abandoned; its owners left for a safer place and gave the key to their neighbour. The man did not resist and handed over the key immediately, but the Kadyrovites threw him to the ground and beat him up anyway. They yelled at him; said he gave them the wrong key. It turned out that they somehow failed to open the lock although the key was the right one.

The man’s wife was trying to rebel against the soldiers, but they would yell at her: “It’s our rule here now!”

Nastia also says that her relative lives in the locality of Krasne where 14 families were kicked out of their homes with no longer than five minutes to pack their things. The soldiers simply took the houses away from them; and they only wanted houses with a fireplace. The locals took care of the homeless families, of course.

Having a fireplace or a stove is important here as it gets pretty cold during wintertime. Locals normally use metal potbelly stoves here.

“Many people now speak ill of Ukraine, they say, bombing is unacceptable as there are people here,” Daria says. “I think it’s OK to be fair. We decided to stay here instead of moving elsewhere, and this put as at risk, yes, no matter where you are, at home or in the centre of Kherson. Ukraine has told us many times: use any chance to leave this region. If you’re still there, try not to walk outside without a good reason, and stay away from the buildings where Russia’s soldiers stay. They told us the missile strikes would be a thing someday. We would have left now, but there’s currently no way of getting out by car. The ferry isn’t safe as Russians use it to transport petrol. When there’s a strike, our people jump out of their cars and hide in trenches side by side with the occupiers. Different people treat this situation differently. But the general logic is: ‘How do we abandon the house if we did the renovation there and even set up the Internet cable?’”

Делайте «Новую» вместе с нами!

В России введена военная цензура. Независимая журналистика под запретом. В этих условиях делать расследования из России и о России становится не просто сложнее, но и опаснее. Но мы продолжаем работу, потому что знаем, что наши читатели остаются свободными людьми. «Новая газета Европа» отчитывается только перед вами и зависит только от вас. Помогите нам оставаться антидотом от диктатуры — поддержите нас деньгами.

Нажимая кнопку «Поддержать», вы соглашаетесь с правилами обработки персональных данных.

Если вы захотите отписаться от регулярного пожертвования, напишите нам на почту: [email protected]

Если вы находитесь в России или имеете российское гражданство и собираетесь посещать страну, законы запрещают вам делать пожертвования «Новой-Европа».