A scandal has erupted on the web in Russia, and one can barely believe that it is possible in the current state of the country. Alexey Zhuravlyov, deputy of the Russian Parliament's State Duma from the notorious Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) and chair of the Rodina (Homeland) political party, openly threatened to murder Björn Stritzel, German war correspondent for Bild, while on air during a political talk show on Russian TV. However, his remarks, surprisingly, fell flat. Zhuravlyov is now facing criticism from all sides and will have to explain himself before his parliamentary faction.

Ira Purysova, a correspondent for Novaya Gazeta. Europe, reports the story of propagandist and jingoist Zhuravlyov and explains why he was condemned for the comments made on a TV programme not known to have ever been tactful before.

“I want to tell this Nazi — and I don’t care! — tell him that we will come and kill you all!” Zhuravlyov screamed on air of the programme 60 Minutes, transmitted by Russian state-owned channel Russia-1, on 5 August.

His outburst came after the show had played a video report made by Bild. Going by the channel’s translation, Bild journalists featured in the video clip were outraged that Russian propagandists regularly brand them as “Nazis”. War correspondent Björn Stritzel also shared his opinion on the subject, and by doing so infuriated Zhuravlyov.

Anyone who watches the channel regularly would not notice anything unusual about what happened. Parliamentarian Alexey Zhuravlyov is featured so often, one could think it was his second job. This summer alone, he has been invited to 60 Minutes at least 42 times. Even his trip to Donetsk did not get in the way of him appearing on the talk show, he went live directly from the occupied territories.

Zhuravlyov’s most notorious quotes are regularly posted on his social media profiles.

“It will become clear to everyone who is fighting there — Georgians and other vermin — that you will die there, scum, or you will be shot dead on court’s orders,” he said live on 9 June while discussing death sentences for British soldiers in the self-proclaimed “DPR”.

“There is no need for referendums! These are our historic lands, what referendum are you talking about!” is how he called for annexation of the occupied territories in late July.

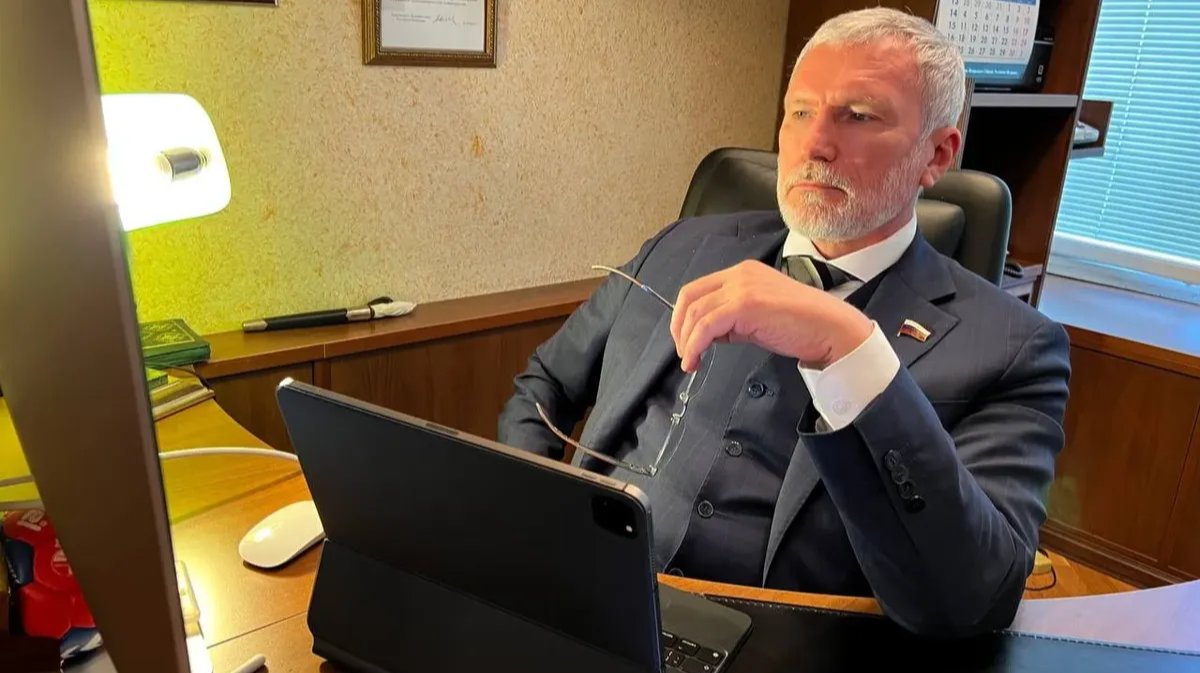

Zhuravlyov during an episode of 60 minutes, 5 August. Screenshot from a video

These and other comments by Alexey Zhuravlyov are usually followed by laughter and cheers from other guests and hosts, Olga Skabeyeva and Yevgeny Popov. And it seemed like the death threat against the foreign reporter on 5 August was pretty much in line with everything else usually said on the programme. However, this time around, even one of the hosts, Popov, tried to calm the politician down.

“Alexey. This is a journalist. A propagandist. No need for this. There’s no need to kill anyone. You are threatening people right now, live on our programme,” the host said to pacify Zhuravlyov, while he continued to rage.

However, a few days later, it became clear that Popov was not the only one to notice that the deputy had gone way too far. In a few days’ time, after the media had picked up on the comment, the LDPR parliament faction condemned his words. Zhuravlyov’s colleagues said in an official statement that the comments represented the politician’s private opinion; death threats were “definitely not something that the party condones”. In September, his actions will be reviewed at a general faction meeting.

Popov, who got lucky enough to deal with Zhuravlyov that day, also had to explain himself.

“In my opinion, Alexey Zhuravlyov wished death on foreign mercenaries and not the German propagandists. At least that is how I wish it was,” he said when speaking to reporters. In the same conversation, Popov assured his colleagues that the politician had pledged not to use death threats again.

The debate about the incident, however, did not quiet down. Moreover, the topic is still getting traction. The main question being asked is: who is this Zhuravlyov (since he allows himself to say such things)? Also, more importantly, why was it decided to bring him down a notch, this time?

Cult follower, nationalist, and patriot

In late June, Zhuravlyov celebrated his 60th birthday. This occasion was acknowledged by Russian President Vladimir Putin and First Deputy Chief of Staff of the Presidential Administration Sergey Kiriyenko: Zhuravlyov was showered with praise for significant contributions to the process of implementation of Russia’s state policies.

Zhuravlyov falls under the category of ultra-right politicians — their time to shine came after the war had broken out in Ukraine. The Rodina party, which he heads, branded itself as Putin’s special forces in the early 2010s and viciously exploited warmongering rhetoric. Zhuravlyov himself used to put on camouflage to attend party conventions. After hostilities in Ukraine had broken out in 2014, he repeatedly visited the occupied territories in the self-proclaimed Luhansk and Donetsk “people’s republics”.

Alexey Zhuravlyov (on the right) with Mayor of the city Debaltseve, Alexander Afendikov (on the right), in the “DPR”, 1 March 2015. Photo: Facebook

Despite his militaristic appearance, Zhuravlyov has never served in the army. His career began in Russia’s Voronezh in the mid-1980s and was reported by journalist Vladimir Tikhomirov to be very similar to that of an average Communist Youth Union activist. After graduating, Zhuravlyov began working for a construction bureau where he quickly rose in the ranks.

The politician’s life changed dramatically in the 1990s when he met Sergey Romanov, founder of Russia’s boxing union, a sports organisation with an ideology behind it which was sometimes labelled as a cult (which regional media also sometimes referred to as, as a result — editor’s note). One of the alleged members of the union told reporters back in the 1990s that fighters were involved in Christian and Buddhist rituals; to be certified, they needed to work on construction sites “almost for free”. Zhuravlyov was one of the “masters” in the union or, simply put, teachers.

In 1994, Zhuravlyov first started getting involved in election politics together with his union fellows, though unsuccessfully at first. The fighters lost the municipal elections, for which one of Zhuravlyov’s friends, Sergey Kazbanov, was running. However, the campaigning itself brought rewards — they received an offer to work in the Voronezh city administration, in the information and analytical department, but they did not last there for very long. According to Tikhomirov, after media reports had emerged of alleged members of the union comparing the organisation to a cult, Zhuravlyov and his friends were sacked.

Tikhomirov wrote about another scandal linked to Zhuravlyov and the pugilism union

at the time when the future member of parliament had been in charge of the economic department of the Communist Youth Union’s regional office. The pugilism union, allegedly, received “a gift” from the regional office in the form of a large amount of money. The politician even sued for defamation after that information had been published. Zhuravlyov demanded 1 million rubles (~€16,000) as compensation but later withdrew the lawsuit (Zhuravlyov’s official biography on the Rodina party website does not mention his cooperation with the pugilism union at all — editor’s note).

Later in 1996, the politician was linked to another patriotic organisation. He was elected as the head of the Russian Community inter-regional public organisation. The organisation later merged with the Congress of Russian Communities, a project created by Dmitry Rogozin, future head of the Russian space agency and founder of the Rodina party. Back then, Rogozin was the chair of the congress. Alexey Zhuravlyov assumed the post of his deputy. At the 1999 legislative elections, Zhuravlyov was a representative of Rogozin who won a mandate.

Rodina’s origins

Rodina is a major milestone in Zhuravlyov’s biography. The party was founded in 2003 by right-wing Russian politicians Dmitry Rogozin, Sergey Glazyev, and Sergey Baburin on the basis of several patriotic organisations. Political strategist Abbas Gallyamov says that the party was planned solely as a project to spoil the Communist Party and the Yabloko party results at the 2003 legislative elections. The experiment was surprisingly effective, and the party won 9% of the votes with 29 mandates. At the same time, Yabloko failed to clear the 5% barrier.

“The party was initially created to counteract very specific players. It then transformed into a more general wildcard that slightly restricted the Communist Party. Although, in reality, it did not have much influence over anything,” Gallyamov says. “The Kremlin didn’t consider it a super important party, rather, it was used to create the illusion of party pluralism.”

A patriotic march organised by the Rodina party, 2 March 2014. Photo: Facebook

Alexey Zhuravlyov did not take part in the party’s successes on the federal level. Between 2001-2004, he continued to work in the Voronezh regional administration, particularly overseeing regional elections.

Zhuravlyov was working for two camps at the 2003 Voronezh legislative elections. The politician was simultaneously heading the election campaign headquarters for the regional office of the United Russia political party and was in charge of the regional Rodina headquarters. This duality did not prove very effective, United Russia only earned 25.85% of the votes in the Voronezh region (with the average of 37.57% across Russia). Immediately after the elections, Zhuravlyov was involved in another election campaign for the office of the Voronezh mayor, once again unsuccessfully.

Tikhomirov spoke to sources in Rodina who told him that, despite these failures, Dmitry Rogozin relocated Zhuravlyov to Moscow to engage him in the regional party-building in 2004.

An inside party conflict was behind that move. Sergey Glazyev, one of the Rodina founders, left after his fellow party members had not backed his candidacy for the 2004 presidential elections. Rogozin wanted someone he could fully control to feel secure in his position. However, Zhuravlyov did not work there long. In 2006, Rodina merged with other organisations to form a new party, A Just Russia: Rodina, Pensioners, Life, and was de-facto dissolved for several years.

Political scientist Ivan Preobrazhensky explains several reasons behind it. First of all, the Kremlin did not like Sergey Glazyev’s opposition politics and decided to strip him of his faction in the lower house of parliament (even though he quit the party). Moreover, after Glazyev’s exit, the party moved along with the radical nationalist rhetoric. The nationalism in the party reached its peak during the 2005 Moscow City Council elections when Rodina had filmed a campaign video titled Let’s take the trash out of Moscow referencing people coming from Russia’s North Caucasus. The video also featured Rodina’s leader Rogozin.

Dmitry Rogozin visits Voronezh, 10 September 2016. Photo: Facebook

“Since then, Dmitry Rogozin was de-facto banned from directly participating in political projects in Russia. Even more so that there were rumours back then that he’d be a possible presidential candidate, an alternative to Putin, and that special forces could back him up,” Preobrazhensky explains. “The Kremlin did not like that this prohibited nationalist rhetoric was used with such ambition. So, Rogozin soon was appointed Russia’s representative to NATO and, later, he advanced his career to government and Roscosmos (Russian space agency).”

However, Rodina was pardoned several years later. In 2011, Dmitry Rogozin moved to a government job and said that Sergey Mironov, chair of A Just Russia, had forcefully seized Rodina. Rogozin vowed to get the control over it back. The inaugural convention of the new Rodina was held in September 2012. Zhuravlyov was then elected as its irreplaceable leader. And even though he did not secure his full authority over Rodina (Preobrazhensky insists that Rogozin is still in control over the party), he very much became its face.

At the time, the BBC’s Russian office linked the revival of the ultra-patriotic organisation with the slumping approval ratings of Vladimir Putin. The party was supposed to unite his supporters under new slogans of conservative patriotism. However, political scientist Konstantin Kalachev points out that “Putin’s special forces” continue to suffer electoral losses time after time. Rodina does not have its own electoral base or a large presence. According to Kalachev, the attempt to bet on the ultra-patriots failed. However, Preobrazhesnky refutes him on this topic, saying that the party is a long-standing project of Dmitry Rogozin that is currently put on hold.

Zhuravlyov’s current fellow party member and an ex-deputy of parliament from A Just Russia, Oleg Pakholkov, describes the chair of Rodina as a person who keeps his word, a good leader and, most importantly, a true patriot. Just like other Rodina members, Pakholkov holds ultra-right-wing views and describes what is currently happening in Ukraine as a “civil war”, where Russians are fighting against Russians “who forgot who they were”.

Oleg Pakholkov, a member of parliament representing A Just Russia. Photo: Facebook

“Zhuravlyov has always immensely supported Russians and Russian people. He is undeniably a person who tends to sacrifice himself for others,” Pakholkov says. “It is a little frightening for me because he can even go to the frontline. We travelled to Donbas together back in 2014. Members of parliament, [we made for] great targets. One might advise staying out of it. But he did not stay out of it, his car was shot at twice (it did happen once, we could not find anything about the second case —editor’s note). He thought that he had to do it.”

Zhuravlyov’s Rodina fellow party members are behind him in the recent talk show scandal. The party is certain that Zhuravlyov’s reaction was completely justified. Senior Rodina member Alexey Ruleyev said that he would “exterminate Nazis” together with Zhuravlyov. Pakholkov told Novaya Gazeta. Europe that the Germans should be grateful that the Soviet Union had “not bulldozed over” the whole of Germany back in 1945.

Smoke and mirror specialist

Zhuravlyov has been working in the parliament since 2004 — at first, he served as Vice Chair of the Rodina parliamentary faction. In 2007, when Rodina was dissolved, he ran for a seat backed by the Patriots of Russia party but did not win. He became a deputy only in 2011, due to him being on the United Russia list.

In the State Duma (the lower house of Russia’s Parliament — translator’s note), Zhuravlyov joined the United Russia faction. According to law, a deputy can join the faction of the party, through the list of which he ran for parliament, or join any other faction, if their own party did not earn any seats. Furthermore, deputies cannot join a faction at all. But Zhuravlyov chose United Russia.

He remained in the parliament for a long time: he kept his seat both during the 2016 elections, and then the 2021 ones. During those elections, Zhuravlyov ran as a member of the Rodina party, first, from the Voronezh region and, then, the Tambov region. Both times, United Russia let him run unopposed.

In the State Duma, Zhuravlyov became part of the Defence Committee, and later, Foreign Affairs Committee. Since 2021, he has served as Vice Chair of the Defence Committee, has become a member of the Commission on Consideration of Federal Budget Expenditures aimed at ensuring state defence and state security.

Fyodor Luginin and Alexey Zhuravlyov. Photo: Facebook

Candidate for Governor of the Kirov region from the Rodina party, Fyodor Luginin, describes Zhuravlyov as a sincere, open, energised man that “unites the power of several people in himself”. He says Zhuravlyov’s patriotic principles — in particular, support of traditional family values — are “in his blood, genetically”.

“It seems that Zhuravlyov is interested in all Russian problems,” Luginin says enthusiastically. “From the most local ones — for example, a leaky roof in the house of an old woman — to global problems such as state defence order. Last year, he visited 150 Russian cities — from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok — and in each region, he made note of locals’ complaints so he could solve their problems. Now, the list of problems, which originally had hundreds of items, is down to basically nothing.”

However, Zhuravlyov’s activity, described so vividly by his supporters, never has displayed itself in the State Duma. From 2016 to 2021, Zhuravlyov was not even part of any faction.

According to political experts Novaya Gazeta. Europe talked to, not belonging to any faction should have led to Zhuravlyov not being able to achieve much in his work. Opposition politician Dmitry Gudkov, who worked with Zhuravlyov during the sixth convocation of the parliament, says that the deputy has never been “a star in the Duma” and, furthermore, was never among the people who determined the agenda.

“There’s not much to remember about him, only that one time when he got into a fight with [United Russia ex-deputy from Chechnya, Adam] Delimkhanov. That was when a gold gun fell out from Delimkhanov’s pocket,” Gudkov recalls, talking about Zhuravlyov. “He’s a freak that talks nonsense, same as [State Duma member] Yevgeny Fyodorov. No one has ever taken him seriously. [It is] now they have become angry and dangerous, because their rhetoric went mainstream, and they became way more famous.”

However, Zhuravlyov’s legislation proposals, despite never becoming laws, often ended up in media headlines. For example, last year, he proposed to create migrant labour camps in Siberia and write a different criminal code for foreigners with more severe punishments. In 2015, Zhuravlyov proposed to start marking brands that used to collaborate with Fascist regimes back in the 20th century and prohibit marriages for transgender people. Before that, he ended up on the news for proposing a bill that would deprive homosexuals of parental rights. Even Elena Mizulina, at the time chairwoman of the Committee on Family, Women, and Children, said that the bill would be impossible to implement.

Political strategist Abbas Gallyamov calls Zhuravlyov’s proposals “self-promotion” and Zhuravlyov himself a “smoke and mirror specialist” — a person that with his actions hides the real, disappointing political process.

“Alexey Zhuravlyov does not play any part in real politics,” Gallyamov is certain.

Political scientist Ivan Preobrazhensky highlights several other important functions of Zhuravlyov. For all these years, he has been the figurehead of the Rodina party, which is why it continues to stay registered, benefiting the party during elections — candidates from Rodina do not have to collect signatures to be nominated. Furthermore, according to the political scientist, in the parliament, Zhuravlyov lobbies for entrepreneurs connected to construction, security, and agricultural businesses (Zhuravlyov has been connected to such firms since the 90s; in 2009-2011, he served as Adviser to the Governor of the Voronezh region and ex-Minister of Agriculture, Alexey Gordeev — editor’s note) and for Dmitry Rogozin.

“Zhuravlyov has basically nothing to do with legislative activity. But he has no need for it, it’s enough for him to be part of committees and commissions and offer, often, the most minimal, technical amendments — before a bill turns into a big legislative initiative,” Preobrazhensky explains.

Aside from lobbying for others’ interests, as a deputy, Zhuravlyov “goes on TV”.

According to Preobrazhensky, for political radicals such as Zhuravlyov, TV is the only format, in which the Kremlin allows them to operate, on the condition that they do not criticise the government. Aside from that, appearing on TV is a good way to make one’s name known, get extra “political weight”, and test certain ideas on the population.

These ideas can sometimes be dangerous. For example, the German journalist murder idea. Thus, the political scientist does not see anything weird in the attempts of propagandists and LDPR deputies to “disown” Zhuravlyov. His explanation is: “The threat was pronounced at the wrong moment.”

“The politician will not necessarily get gag orders after this, he can talk from his own point of view,” Preobrazhensky adds. “All propaganda is a swarm of bees. Usually, these people know what and when to say. It is obvious that Zhuravlyov went too far, because, for certain, there are currently some negotiations with Germans about the fate of North Stream 2 going on. The Kremlin does not need another scandal that could become a reason to cease all contact with Russia.”

Still, no one made Zhuravlyov quit TV for his “ruthlessness”. The politician appeared in the next episode of 60 Minutes, the day after the scandal.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]