When Andrey and Natalia Smekalin and their four children were reunited in Paris last month, it was the first time that they had all been together in over a year, since Natalia had deserted her military post in Russia’s Far East and fled to Armenia, despite intimidation and threats from the Federal Security Service (FSB).

Fearing denunciation for his political views, her husband Andrey had already left Russia, taking two of their children with him. For months, the family lived divided by borders and time zones until late last year, when the French Foreign Ministry unexpectedly issued Natalia and her two youngest children with international travel documents, allowing them a legal route to France, from where they are all now applying for political asylum together.

Speaking to Novaya Gazeta Europe, the Smekalins described how their once-happy family life turned into a nightmare after the start of the war — and why, in the end, leaving Russia became their only option.

The Smekalin family. Photo: personal archive

Antebellum

“My father was a serviceman, and when I was 19, I was offered a job in the personnel unit, working with documentation,” Natalia, now 38, says. “I liked the job. Two years later I signed a contract and stayed on at headquarters, doing clerical work.”

“It’s not that I loved the army — I have a musical education — but there was simply no other work in the town. I enjoyed reading reports, drafting paperwork. I was always surrounded by documents. I was a part of what we used to refer to as the ‘paper army’. I even planned to become a warrant officer, but in 2010, just as I finished technical college, the rank was abolished. So I remained a junior sergeant.”

“I immediately understood that sooner or later we would have to leave the country.”

By the time Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Smekalins had three children: a six-year-old daughter, a seven-year-old son, and a three-month old baby boy. Natalia was on maternity leave.

The news of the invasion hit both spouses hard. Andrey held opposition views and had once worked as an election observer during the 2018 presidential election. He remembers 24 February clearly.

“I felt crushed,” he says. “I immediately understood that sooner or later we would have to leave the country.” Additionally, for Natalia, the war became a deeply personal tragedy.

Natalia Smekalina in uniform. Photo: personal archive

The Ukraine connection

“All my family is in Ukraine,” Natalia says, her voice trembling. “We didn’t communicate very often — mostly on holidays — but the first thing I did on 24 February was contact them. I began every message with an apology. I understood perfectly well what had happened, and I apologised every time. I felt complicit in the war because I served in the Russian army.”

“They understood me and accepted that. We still keep in touch. I worry about them constantly. Military drones are launched at targets near to them, there are frequent power and internet outages. They’ve become closer to me than my own parents. My mother and father immediately argued with them. Nowadays, they only watch Russian television and believe all the lies being broadcast. They didn’t support me in anything either.”

Later, in 2023, Natalia’s cousin from Nova Odesa, in Ukraine’s Mykolayiv region, was mobilised. While still in Russia, she was afraid to write to him, worried that it might cause him trouble with his commanders. As soon as she reached Armenia, however, she made contact with him and they stayed in touch.

“He was always glad to hear from me, always supportive, saying that ‘we’ll still sit at the same table together one day’,” Natalia says through tears. “Recently, he was killed.”

On the very first day of the war, Natalia decided to leave the Russian military. She submitted her letter of resignation, only for it to be “lost”, something that happened twice.

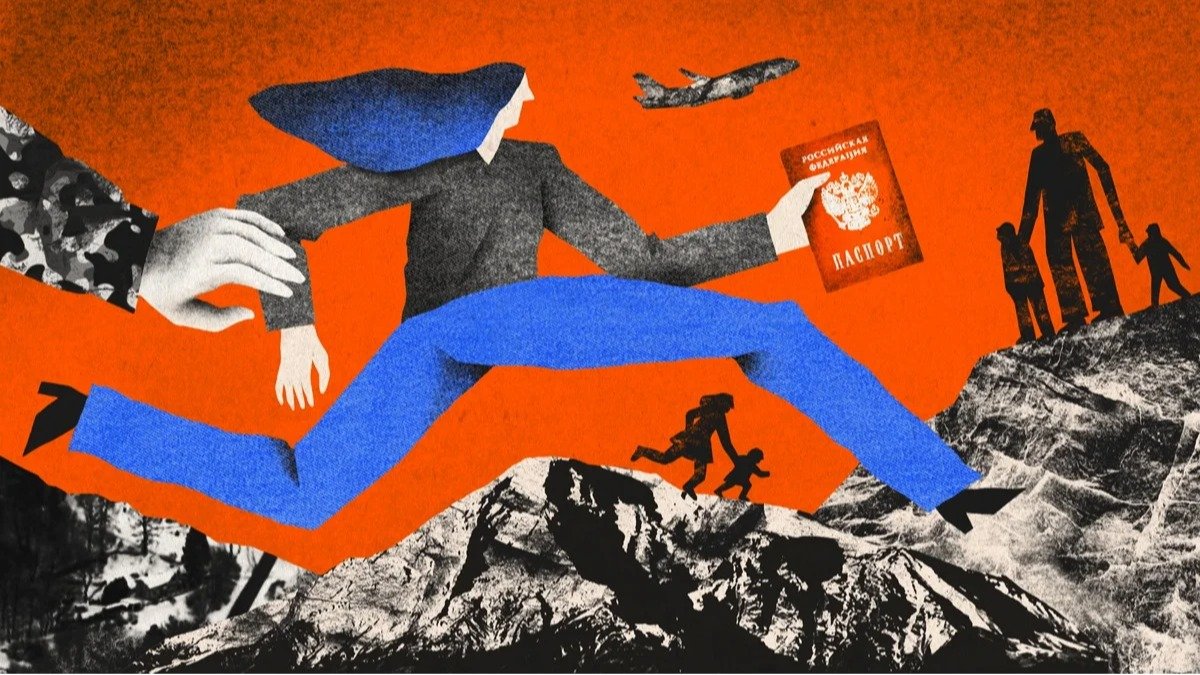

Illustration: Lyalya Bulanova, Novaya Gazeta Europe

Later, the head of the unit responsible for protecting state secrets came to her directly and told her that she would not be able to resign until the end of the so-called “special military operation”. Natalia was aware that this was a lie; the edict making military contracts indefinite was only issued in autumn 2022.

“At the time, it never even crossed my mind that they could send me to the front while I was on maternity leave,” Natalia recalls. “Although even before February 2022, they made us sign statements ‘in case of war and mobilisation’. We were told that those with children under 16 would not be mobilised.”

Andrey came home, looked at their 10-month-old son, and decided he couldn’t possibly leave him and miss watching his children grow up.

She worried more about her husband. “He’s not the kind of person who can stay silent and endure things. We understood that sooner or later someone would report him for ‘discrediting the army’.”

When Vladimir Putin announced the partial mobilisation of Russia’s military reserve on 21 September 2022, Andrey was confident he wouldn’t be called up, as he had been deemed only “partially fit” by the military authorities. While he calmly went to work that morning, a terrified Natalia bought him a ticket to Georgia.

That evening, Andrey came home, looked at their 10-month-old son, and decided he couldn’t possibly leave him and miss watching his children grow up. So, for the time being, it was decided that the family would remain together in Russia.

Andrey Smekalin in Kazakhstan with two of his children. Photo: personal archive

Lives apart

Despite Natalia’s contract becoming indefinite, she nevertheless attempted to obtain a passport to allow her to leave the country. But as one of her duties at work had been sending encrypted telegrams, which gave her second-level security clearance, any travel abroad was going to be extremely difficult.

“I went to ask how I could get a passport,” Natalia says. “The woman from the classified office said I’d need a mountain of documents. In short, they completely ruled it out: they said that as long as the ‘special military operation’ was ongoing, I wouldn’t be going anywhere. At the same time, officers with the same clearance somehow could leave — but I couldn’t.”

The Smekalins lived in this state of anxiety for an entire year. By September 2023, Andrey could bear it no longer and his constant fear of losing his freedom outweighed everything else. He took their eldest son and daughter and drove from Vladivostok to Aktau, Kazakhstan.

She dreamed of reuniting with him and leaving Russia too — but military bureaucracy stood in the way.

“I didn’t feel safe,” Andrey says. “First, if I had been served a mobilisation summons, I would have been barred from leaving the country. Second, people had changed — it was as if they’d gone feral. I understood that sooner or later someone would report me.”

He recalls an argument with a friend over the war: “He was red in the face, shouting: ‘You’re a traitor! People like you should rot in prison or be sent to the front!’ He said he would definitely report me. That sort of thing sobers you up instantly.”

Natalia admits she “cried constantly” in those first days following her husband’s departure. She dreamed of reuniting with him and leaving Russia too — but military bureaucracy stood in the way.

Under scrutiny

By then, Natalia’s maternity leave was ending. She already knew she could not return to her job as she was determined not to allow herself to be another cog in the Russian war machine. The couple came up with an unconventional solution, which required Andrey to return home briefly.

“Natalia’s maternity leave was ending,” Andrey explains. “She was already talking to her [unhinged] boss, telling him she didn’t want to come back. He told her: ‘Then you’ll just go to prison.’ We were under enormous stress and honestly couldn’t think of anything better than having another child — our youngest daughter.”

Andrey returned to Russia for 20 days in November 2023, terrified in every airport. He then went back to Kazakhstan with their younger son, leaving their eldest daughter with Natalia, who missed her mother desperately.

The decision likely saved Natalia from criminal prosecution. In spring 2024, officers from the FSB attached to her unit took an interest in her. “By then I was already pregnant, but they didn’t know it,” Natalia says.

In front of officials and on camera, she was forced to agree that she was subject to travel restrictions and had no right to leave the country or obtain a passport until March 2026.

She describes how the FSB officer tried to gain her trust, while she “put on her armour”. This continued until May 2024, when a final “conversation” took place. An officer from the military’s state-secrets protection service drove her to Vladivostok.

“I already had a big belly by then,” she recalls. “Maybe they were afraid something would happen to me and the baby and that I’d sue them. When they opened a case against me for violating secrecy regulations to avoid bureaucracy — as I tried to apply for a passport via the state services portal — they didn’t yet know I was pregnant. Once they found out, they became much more careful.”

She was taken to the regional FSB office and, in front of officials and on camera, forced to agree that she was subject to travel restrictions and had no right to leave the country or obtain a passport until March 2026.

After that, Natalia “retreated into a psychological shell” and simply endured. The birth of her youngest daughter allowed her to go on maternity leave again.

Illustration: Lyalya Bulanova, Novaya Gazeta Europe

Taking the Balkan route

After a year in Kazakhstan, Andrey took up an invitation from some friends and moved with his two sons to Georgia, though he now says that at the time he felt as though he was losing control of his life. Like Natalia, bringing the family back together again was all he could think about.

It was a news report about France’s Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs issuing travel documents to six Russian deserters that gave him the idea. The documents had allowed the erstwhile servicemen to enter France without their Russian passports, from where they were able to apply for asylum. In theory, Natalia would also qualify for a similar laissez-passer.

Andrey decided he would go to France first, though as he didn’t have a Schengen visa he took what is known as the Balkan route, crossing the Bosnian–Croatian border to reach the EU. A long-established way for refugees from the Middle East and Africa to reach Europe, since the start of the war Russians have increasingly been attempting the journey too: deserters, for example, or Chechens fleeing the Kadyrov regime.

The Smekalins were fingerprinted, then driven to the railway station and issued with instructions to travel to a refugee camp.

The Croatian border guards are notorious for their brutal and degrading treatment of migrants, something that Andrey and his sons experienced first-hand. Having been held at the border for hours, their bags were turned inside out, and they were sent to a detention centre for immigrants.

Eventually, the officials who had processed Andrey at the border arrived at the detention facility. They reprimanded the local staff for placing a father and two children in such conditions. The Smekalins were fingerprinted, then driven to the railway station and issued with instructions to travel to a refugee camp.

Instead, Andrey bought tickets to Zagreb, where he rented an apartment so the boys could rest properly. In October 2024, he flew with them to France and applied for asylum.

Illustration: Lyalya Bulanova, Novaya Gazeta Europe

Reunion

“Imagine this: I’m on maternity leave, but my youngest daughter will soon be two, and the war is still going on,” Natalia says. “And I don’t know how much longer it will last. But I’m certain about one thing: I will not return to military service. I will not take part in the crimes of our army — not even by pushing paperwork.”

Natalia had known about the Russian underground anti-mobilisation project Get Lost for a long time, and had even corresponded with them about her case, and been advised to flee to Armenia — one of the few countries Russians can enter without a passport, just using their ID papers. On 13 March 2025, Natalia took her daughters and went to the airport.

Though she had no doubt that her decision to desert was the right one, she was understandably terrified of breaking the law, and, above all, of falling back into the hands of the FSB.

Despite her anxiety, the trip to Armenia went smoothly. Still, Natalia remembers how her passport was checked for 20 minutes before departure at the airport, overwhelming her with fear and anxiety. “They were examining my passport as if under a magnifying glass, my whole life flashed before my eyes. I thought they’d definitely found me in some database and that this was it, the end. But thank God they let me through.”

Andrey and Natalia Smekalin. Photo: personal archive

Upon her arrival in Armenia, Natalia burst into tears. Once there, she looked after her daughters as best she could and lived off the family savings, but her day-to-day existence was riven with tension, and she was constantly afraid that the Russian security services might track her down.

Fortunately, the constant stress was eased by the hospitality and kindness of Armenians. “Armenia is just an incredible country,” Natalia says. “Everyone is so helpful. Your shopping bag tears — someone comes over and helps you pick everything up. A little one falls over, even on soft grass — people rush to help. The landlord [of the flat we rented] was amazing too — helping me carry the pram down the stairs, for instance.”

Natalia still did not have a passport, and she was too scared to apply for one at the Russian Embassy in Yerevan, fearing it would reveal her whereabouts to the authorities. Instead, she applied for laissez-passer documents at the French embassy, with the help of the refugee support group Intransit.

The family had begun to lose hope — until the good news finally arrived. “When the human rights activists told me the laissez-passer had been approved, I didn’t believe it,” Natalia recalls. “Lately my husband and I felt the process was taking forever, and we didn’t believe anything would come of it. He was already ready to give up and come to live with me in Armenia. When I finally arrived in France and saw him, I just broke down crying. And even after we spent our first day together… we still can’t fully process it, still can’t believe it happened. That we made it through. That we were strong enough.”