In recent years, two clear trends have emerged in Russia’s once thriving cinema industry: the use of fairy tales and the telling of stories from Russia’s regions. If the appearance of fairy tale in film speaks more to a desire to escape the ongoing war in Ukraine and Russia’s looming economic crisis, the rise of regional cinema arguably points to the growing demand among the country’s non-ethnic Russian populations for cultural self-determination.

Whether in Yakutia or Altai, these films often speak to the viewer in the language of myth and place children and their relationships with their parents at the centre of the action. The “regional fairy tale” movie allows filmmakers to reflect on the dying out of once vibrant cultures, historical memory, and the ghostly presence of the Soviet past, which is brought to life again on screen seamlessly.

Despite the understandable reluctance of many cinema goers to watch Russian films made since the invasion of Ukraine, Novaya Europe’s film critic Vladimir Kocharyan has selected five features made in Russia’s multitude of regions that reveal the anxieties, hopes and doubts of a society undergoing radical change.

Timir (Nikolay Koryakin, 2023)

After his mother’s death, the young Timir is forced to leave Yakutsk, the capital of the giant Sakha region in Russia’s Far East, and move in with his father, whom he has not seen for many years. Once absent from the family altogether, the father now lives in a remote village, spending his days in the grip of alcoholism and the company of fellow drinkers. Timir feels like he’s travelled back in time: the village seems frozen in the atmosphere of Soviet pioneer childhood. The local school principal, with the zeal of a middle-aged Komsomol activist, urges the boys to be disciplined and dutiful, but childhood remains childhood — it’s all about breaking rules and looking for adventure.

A promotional poster for Timir. Photo: Fund for the Support of Regional Cinema

Timir arguably has enough adventure to deal with at home, however, coping with his father’s alcoholism as well as the vast emotional distance between them. An unexpected helper appears in the form of a local ghost, whom Timir meets in a lot of abandoned cars. Wearing a cap emblazoned with the letters CCCP, the ghost promises to help Timir reconnect with his deceased mother. In return, he asks for help in leaving this world himself — a world in which he has long been trapped, unable to find an exit.

Timir may be Nikolay Koryakin’s debut feature but it has already earned him the Best Director prize at Moscow’s Zimny festival. Critics have noted the film’s visual affinity with the work of Wes Anderson, and it’s true that Koryakin’s geometric framing and rigorous composition lend each scene the quality of a self-contained visual statement. Koryakin adopts this approach as a structural foundation, but pushes it into territory where Yakut cinema has long been at its strongest — the realm of magical realism.

While the ghostly companion becomes a way for Timir to process loss, for the audience, it’s more of a symbol of how the village remains in thrall to its own past. Suspended in a limbo of Soviet and Komsomol aesthetics, villagers find themselves unable to fully grow up, just as the ghost cannot finally depart until the era whose emblem he wears on his cap has vanished for good.

Take It and Remember (Baybulat Batullin, 2023)

A still from Take It and Remember. Photo: Fund for the Support of Regional Cinema

Six-year-old Ilkhas spends the summer in a sun-drenched Tatar village. His parents have gone away and left him in the care of his grandmother Sufiya and grandfather Rasim. The days unfold in an atmosphere of lightness and play: one day he and his grandfather are absorbed in board games, the next they dress up as superheroes, while on another they sing songs together, as neighbours drop in, eager to join the games.

Only Sufiya’s distant manner hints that something is amiss. In the evenings, Ilkhas tries to call his parents. Each time he hears the dial tone, followed by the same automated voice saying that the subscriber cannot be reached. The whispered conversations behind his back grow quieter, and tears can be seen in his grandparents eyes as they try to avoid his looks — llkhas’s parents have died in a plane crash.

The loss sees Sufiya lose the will to live, while Rasim seeks oblivion in alcohol. Only the games go on — louder, brighter, more insistent — as if they might delay the moment when the child will have to learn what loss means.

How does one begin the most difficult conversation of all — about the end of life? This is the question posed by Tatar director Baybulat Batullin. Take It and Remember is a story whose aim is not to carry the viewer away into a world of magic or nostalgic reverie, but rather to sober them up and confront them with a reality one can try to avoid for a long time.

The comic form serves merely as a mechanism for holding the viewer’s attention: the director, like an adult with a child, draws the audience into the narrative and then, at a certain moment, leaves them alone with the necessity of understanding. The hero’s microcosm is reduced to a small village house, the place his parents came from.

The house is surrounded by the endless Tatar steppe, where it is difficult to determine the time in which the action takes place. The film claims to be set in “the present day,” but it feels like a frozen timelessness in which details of the present occasionally flicker through.

The link between time and generations is provided by the soundtrack: Batullin deftly mixes the Soviet-era Tatar icon Alfiya Avzalova with the indie electronic group Taraf, creating a rhythmic bridge between eras — the very bridge that the film itself becomes.

The Black Notes (Anatoly Koliev, 2024)

A still from The Black Notes, 2024. Photo: Fund for the Support of Regional Cinema

The year is 1942 and World War II is in full swing, leaving a mountain village in North Ossetia in the Caucasus inhabited mostly by women whose husbands and sons have been sent to the front. From time to time the silence of the mountains is shattered by a woman’s cry: another letter has arrived — another man will not be coming home. These notices are delivered by the local postman, a young man who, aside from a handful of teenagers and elderly men, is the sole male left in the village.

At one such moment, two brothers, Dzambol and Ilas, decide to interrupt the flow of grief, if only briefly. They strike a deal with the postman and begin hiding the letters in the walls of an old fortress. Meanwhile, their mother, Dzerassa, waits for news from her husband Kazbeg, who has gone to war. She, too, struggles to keep despair at bay, but rather than accept the present, she turns to ancient magic, attempting to glimpse a future in which her husband is still alive.

The partnership of two young Ossetian brothers, director Anatoly Koliev and screenwriter Alan Koliev, transforms a family story into a Gothic fairy tale in which each frame resembles a carved fresco, painted in a restrained palette of black, blue, and brown. Ossetia appears not merely as a mountainous republic, but as the wellspring of a rich folkloric tradition that is little known elsewhere in Russia.

Legends and epic motifs are woven seamlessly into the narrative, making the mystical an integral structural element rather than a mere bauble. Though it may not be comparable to Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, The Black Notes represents a confident step beyond the familiar conventions of World War II movies.

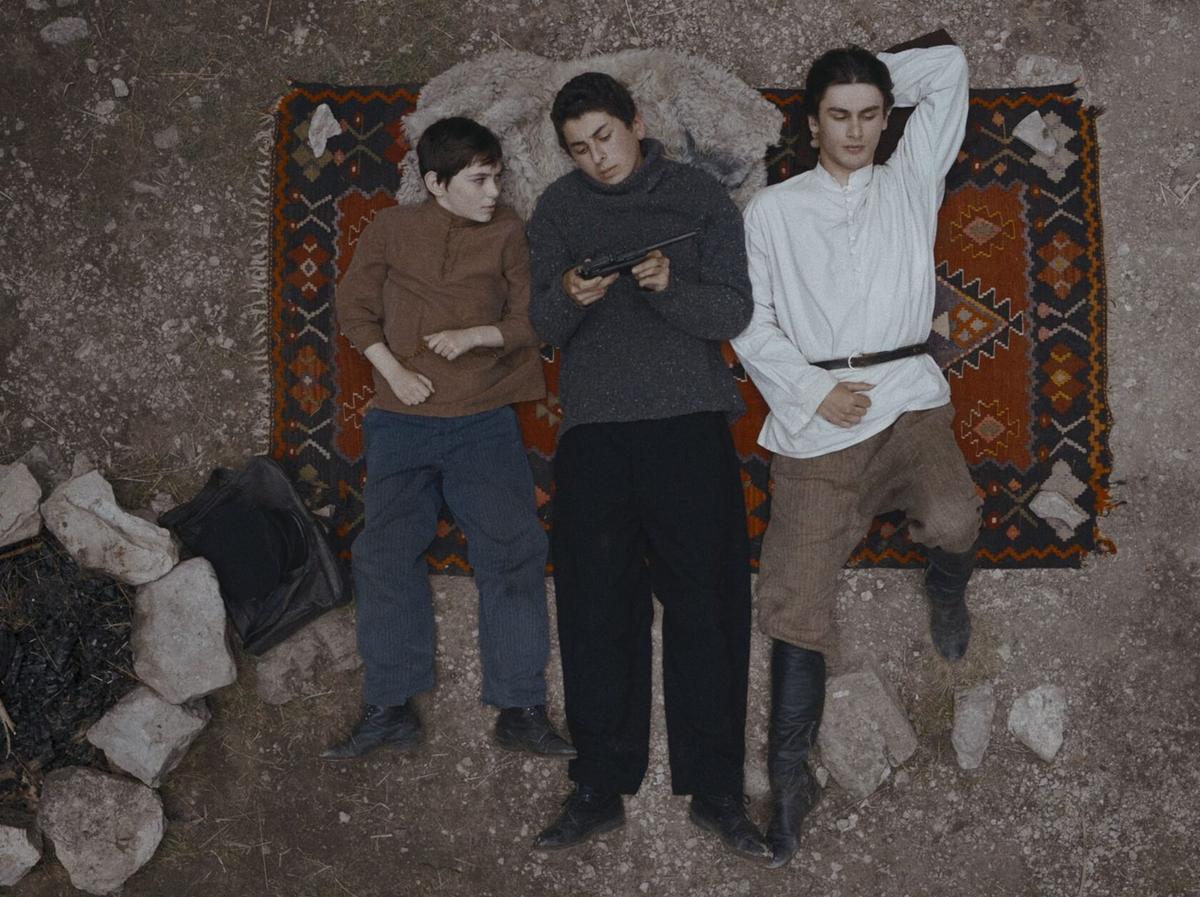

The Wolves (Mikhail Kulunakov, 2024)

A still from The Wolves, 2024. Photo: Okko

Set in Siberia’s Altai region during the 19th century, when clan-based customs and ancestral ways of life still endure in the mountains, The Wolves tells the story of Tokma and Kymyskai, whose love for one another is thrown into doubt when Kutus, a wealthy neighbour who has his own designs on Kymyskai, decides that she must become his wife. Rather than discussing that with her, Kutus, following ancient custom, asks her father for her hand in marriage. Once he agrees, she is abducted and taken to Kutus’s ancestral home. The more fiercely she resists the future imposed on her, the more insistently Kutus seeks to possess her.

But the heroine refuses to surrender her will. Even though disgraced, she finds the strength to flee her abuser and return to the man she loves. Years pass. On a remote mountain edge, Tokma and Kymyskai create a family refuge hidden from prying eyes; they have two sons.

Both are equally loved by their mother, but the heavy gaze of the father betrays a resentment that, over time, breaks through in words and actions toward the elder son — the one who forever reminds Tokma of the shame and violence that haunt their family like a shadow.

From the very first minutes, the viewer is immersed in the world of late 19th-century Altai: meticulously designed costumes, household objects, and interiors bring the past to life on screen, at the heart of which are reflections on the source of cruelty.

Two years earlier, Mikhail Kulunakov made The Trail, Altai’s first full-length feature film, in which a lone hero cuts a path through the mountain. With The Wolves, Kulunakov continues to forge his own path in the film industry, choosing the thriller genre and using the culture of his native land as its setting. Kulunakov moves beyond a mythologised image of Altai, blending elements of the “eastern” and the thriller. This not only gives the narrative the necessary momentum but also deepens the viewer’s emotional involvement in the fates of its characters.

Although most of the screen time is devoted to the conflict between the adults, the director shifts the focus to the two brothers — both victims and heirs of the pain passed down to them by their parents. It is they who become the “wolves”, destined to enter the future bearing the burden of a family tragedy. Their howl is met by a new era, bringing with it different catastrophes, capable of forever changing the lives of everyone in the Altai.

Legends of Our Ancestors (Ivan Sosnin, 2025)

A still from Legends of Our Ancestors, 2025. Photo: Kinopoisk

Though Anton is a prize-winning journalist at a Yekaterinburg newspaper, his wife has left him and taken their daughter to live with her in Moscow. He does not remain alone for long, though, and unexpectedly finds himself in the company of Nyulesmurt, a forest spirit only he can see.

Nyulesmurt has his own troubles, though: his strength is waning, and in time — along with his kin, the gods and spirits of the Urals — he may vanish entirely. The only way to preserve this hidden world is to remember their names and to tell their stories, especially to children.

At first, Anton refuses to help this mysterious visitor who has appeared so suddenly in his life. But Nyulesmurt, with a touch of cunning, convinces him that if he succeeds, he may restore what he values most — his lost family.

Ivan Sosnin, a rising talent in Russian cinema, draws on his native Urals as the setting for his films — first in The Alien, and now in Legends, where he places the mythology of the region’s indigenous Khanty and Mansi peoples at the heart of the story. The magical beings losing their names mirror the fate of these cultures, threatened by the dwindling numbers of people who speak these languages and bear their traditions.

Framed as a road movie, Anton’s journey with these mythic figures is less a tour of the region’s geography than a passage through its deep layers of memory, a landscape that preserves a singular cultural code. The allegorical structure in which Sosnin presents the dying out of these cultures also allows for hope: memory is transmitted from one generation to the next through storytelling, and with it, the names of ancient myths and epic traditions are brought back to life.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]