On 17 April, state-controlled broadcaster Channel One aired a documentary supposedly chronicling what was described as “the most successful military operation” of the war to date. The operation was said to have facilitated the Russian military’s decisive attack on Sudzha, a town in the Kursk region that had been controlled by the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) since August of last year. It was called Operation Stream, because Russian troops had to make an arduous journey through a disused gas pipeline to attack the Ukrainian military.

Operation Stream was carried out in early March, and for nearly two months Kremlin officials and propagandists have been touting its achievement as a heroic narrative. But this attempt at myth-making has raised far more questions than answers.

Preparation

On 8 March, Russian troops managed to penetrate enemy lines by walking through the disused Urengoy-Pomary-Uzhhorod gas pipeline. It had been the main conduit for Russian gas exports to Europe, until, at the start of this year, Ukraine declined to renew a transit agreement and the fuel supplies stopped.

A state-owned news agency reported that several army brigades took part in Operation Stream, including servicemen from the Volunteer Corps and Chechen special forces. The Channel One documentary claimed that the team had spent 100 days in preparation.

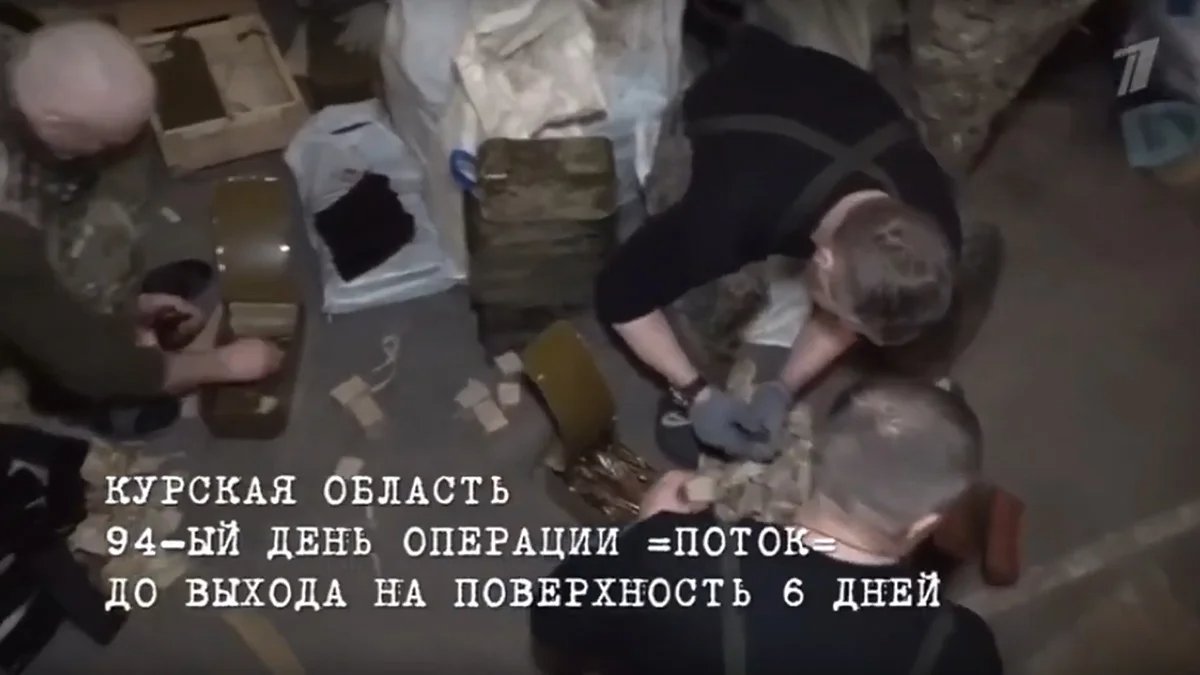

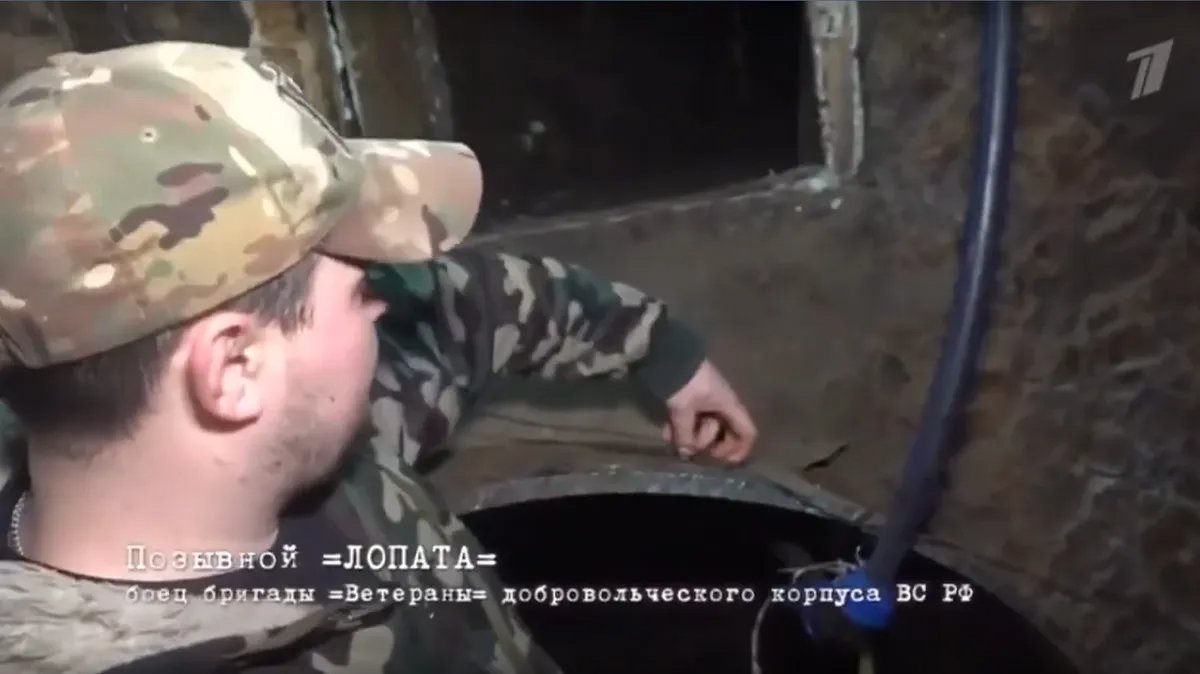

Scene from documentary Operation Stream. Source: YouTube/Channel One

And suddenly cracks started to appear in the Kremlin’s narrative. A former Wagner Group commander with the callsign Zombie said that prepping the operation had actually taken a little more than three weeks.

Due to residual gas in some parts of the pipeline, the soldiers were required to use oxygen tanks as they crawled 14 kilometres through the pipeline over six days, according to acting Kursk region Governor Alexander Khinshtein. After receiving the go signal, Zombie said the Russian troops exited the pipeline and occupied an industrial zone just outside Sudzha, from where they began their assault on Ukrainian positions, taking the AFU by surprise and leaving them “disoriented”.

At this point, the Russian and Ukrainian narratives begin to differ starkly. While Ukrainian sources confirmed that Russian troops did indeed manage to penetrate Ukrainian defences by passing through the pipeline, they insist that the operation had been detected prior to the assault; as a result, they said, AFU troops were lying in wait for the Russian soldiers, many of whom were cannon fodder as they emerged.

Scene from documentary Operation Stream. Source: YouTube/Channel One

Gas poisoning

Russian military blogger Vladimir Romanov reported casualties during the operation on 9 March. Praising the Russian troops who lost their lives, Romanov called them “real warriors”, for “completing the task” and “not flinching” despite being aware that they were “dead men walking”.

On 17 March, the regional Russian news outlet URA.RU reported that two Russian servicemen from the Chelyabinsk region in the Urals had been injured. Both men, Yevgeny Zaytsev and Denis Khusainov, had been hospitalised for gas poisoning. Khusainov has reportedly returned to active duty service.

Over 800 people were stationed in the gas pipeline with dwindling oxygen supplies, according to the documentary, which depicted troops losing consciousness and one serviceman saying he could hardly move.

A commander in the Chechen Akhmat Brigade known by the callsign Hades said that the Russian troops involved in the mission had only been briefed on its nature at “the last moment”. When troops were informed that they would be crawling through a disused gas pipeline just four hours before the operation began, Hades said, they “listened to the task in cold blood, as befits real Russian warriors”.

In the documentary, Channel One correspondent Amir Yusupov demonstrated how men of varying ages and physical fitness squeezed into the pipeline. On the morning of 6 March, when the assault was scheduled to begin, Yusupov said that not everyone had reached their intended exit points because of overcrowding. Then melting snow clogged the ventilation holes with mud.

The day before the assault, over 800 people were stationed in the gas pipeline with dwindling oxygen supplies, according to the documentary, which depicted troops losing consciousness and one serviceman saying he could hardly move.

Pipeline replica in Yekaterinburg. Photo: Podyom Telegram channel

Propagating the myth

Since March, pro-Kremlin media outlets have consistently attempted to create a heroic narrative out of Operation Stream, filming documentaries and organising public exhibitions. Russian pro-war military commentator and retired colonel Viktor Litovkin told one regional news outlet that Operation Stream would “of course go down in history”.

On 11 April, a metre-long fragment of the pipeline was placed on a black pedestal in the centre of Kursk. Nearby, the Kursk Drama Theatre put on an exhibition of photographs and personal belongings of those who had participated in the operation. More than 1,600 kilometres away in Yekaterinburg, the Russian Orthodox Church unveiled a replica of the pipeline, so that citizens could “experience what Russian troops endured”.

Russian commanders only decided to continue the operation because “so much effort and so many resources had already been spent”.

Despite official attempts to glorify Operation Stream, others with knowledge of the operation claim that there was no decisive battle. A Russian military expert whom we’ll call Ivan Kuznetsov maintains that by the time the operation was underway, the Russian military had begun its final onslaught on Sudzha and had “already practically cut off” Ukrainian forces from their supply lines.

By 8 March, when Operation Stream began, Ukrainian troops were in the process of withdrawing from the area, said Kuznetsov, abandoning villages with “virtually no fighting” and leaving behind only the rearguard units to cover enemy fire. In his telling, Russian commanders only decided to continue the operation because “so much effort and so many resources had already been spent”.

Kuznetsov contends that Ukrainian intelligence likely assumed that Russia was planning on breaking through its defences and planned a rapid retreat. The Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) have also stated that they were aware of the impending attack and fired at the Russian troops who emerged from the gas pipeline.

Scene from documentary Operation Stream. Source: YouTube/Channel One

Unanswered questions

Questions remain about the scale of the operation and the extent of its losses. State media has reported that several hundred servicemen were involved, with figures ranging from 600 to over 800. Other sources indicate that it was in fact a much smaller operation: the breaking news Telegram channel Mash reported that about 100 servicemen were involved, while drone footage shows a dozen or so Russian soldiers, and the documentary footage highlights just a few so-called heroes of the operation.

The number of Russian casualties has not been reported by state media. Commander Barkas of the 30th Motorised Rifle Regiment said that he was glad Russia only suffered “minor losses”. The Channel One documentary showed relatively few bodies scattered on the ground.

The only thing that is clear is that Operation Stream has already become a myth.

What exactly was the Channel One film crew’s access to Operation Stream? The documentary appears to show the operation in its entirety — filming even during its preparations — but how does that square with the assertion that the operation was of the highest secrecy? Why, when the documentary premiered around a month after the operation took place, did it add so little new information? Other news agencies had released virtually identical reports weeks earlier.

It is entirely unclear how much Operation Stream actually contributed to Russia’s recapture of Sudzha. The Channel One documentary shows six soldiers holding a Russian flag against the background of destroyed buildings, supposedly in Sudzha, but a full five days after the troops emerged from the pipeline.

The only thing that is clear is that Operation Stream has already become a myth.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]