Last autumn saw a wave of raids by police officers on queer venues in Moscow to scrutinise their compliance with the country’s increasingly homophobic legislation. Armed police terrified revellers, forcing them to lie face down on the floor, sometimes for hours at a time, beating and humiliating some, while checking the documents and phones of others.

Moscow’s nightlife scene has changed dramatically amid police raids and increased persecution of queer Russians since the Russian Supreme Court outlawed the “international LGBT movement” in 2023.

In one of multiple examples, queer space Inferno shut down permanently within two weeks of the police interrupting a show there. Other venues that were once known for being queer-friendly spaces have adapted to recently adopted homophobic laws while attempting to demonstrate their political loyalty to the Kremlin in the hope of avoiding fresh raids.

Novaya Gazeta Europe visited a Moscow club to see how once openly queer venues and their clientele have adapted to the rules now governing behaviour.

‘People in masks came storming in’

Friday night, and revellers are streaming into Moscow’s nightclubs. Having shopped the capital’s nightlife offerings online in advance, I settle on a venue I’ll call Club X in the interest of their security.

“We had lists of banned performers,” she says. “They included artists who were of Ukrainian origin or were included in the list of foreign agents. We couldn’t perform to their songs, and DJs weren’t allowed to play them.”

Tonight, Vladim Kazantsev, better known as drag queen Zaza Napoli, is due to perform — but, like many other performers working at the club, he will not be appearing in drag, a decision taken by Kazantsev after a party he was performing at was raided in the western Russian city of Voronezh in November.

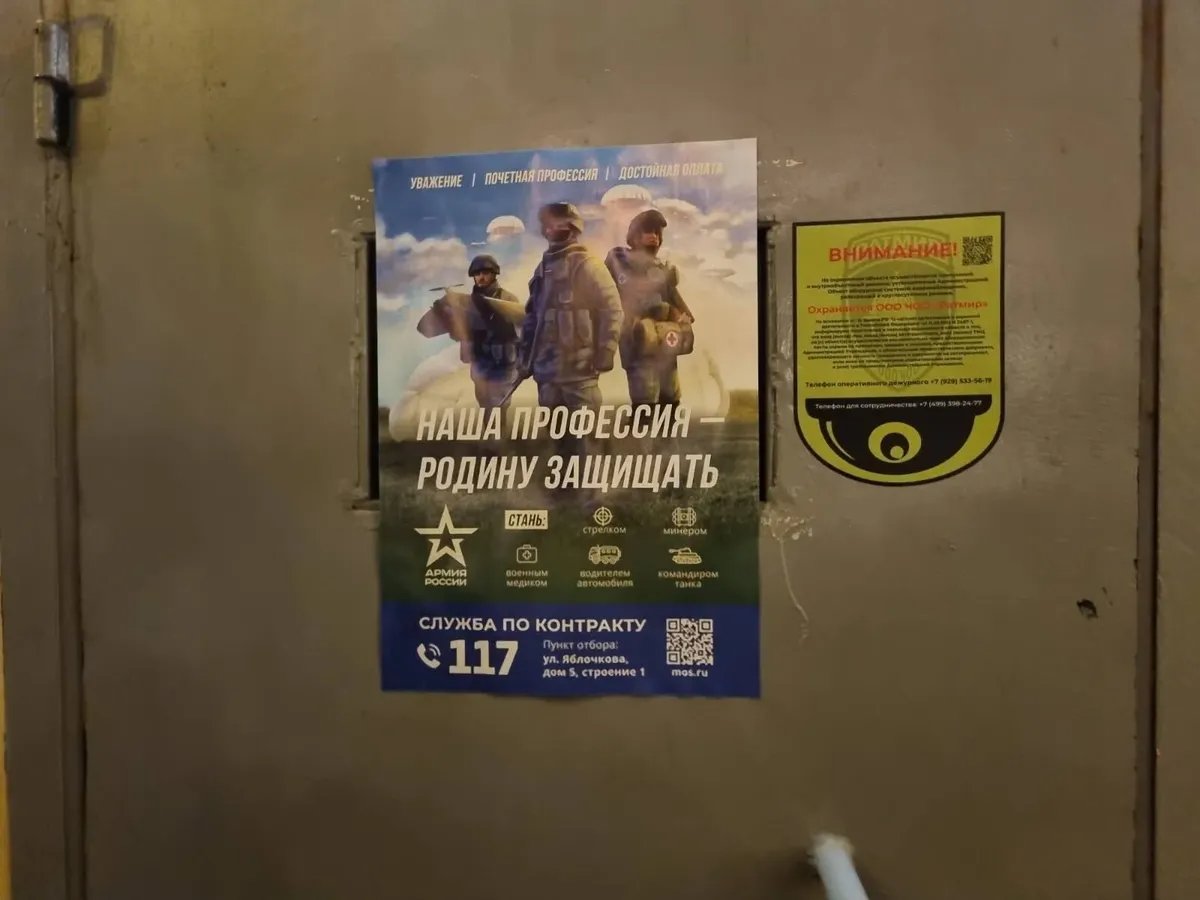

I arrive at about 11pm and am asked for my ID at the entrance, which the staff check carefully before letting me in. Once through the door, I am immediately confronted with a poster encouraging people to enlist in the army.

Today there is a special offer: party-goers under the age of 28 can drink cocktails for free until 2am in one of the bars. It works — the dance floor is almost empty, but there are dozens of people clamouring for free drinks. I order champagne from a shirtless bartender, sit on a couch and look around me. Some people knock back their free cocktails and immediately queue up for a refill, others break off into small groups and dance in a small sideroom.

An army recruitment poster is prominently displayed inside the club. Photo: Matvey Leybin

The room next to it is for karaoke, and partygoers are singing songs by well-known Russian pop stars. A woman of about 30 asks for a song by Ukrainian singer Loboda, but a member of staff says they don’t have it and asks her to choose another artist.

Moscow queer clubs stopped playing tracks by “banned artists” long ago, drag queen Nicky Jamm, who left Moscow for Belgrade after the autumn raids, confirmed to me subsequently.

“We had lists of banned performers,” she says. “They included artists who were of Ukrainian origin or were included in the list of foreign agents. We couldn’t perform to their songs, and DJs weren’t allowed to play them.”

A dark-haired man of about 20 introduces himself as Ivan*, before telling me that he’s been a regular at the club since he moved to Moscow from a small town on Russia’s Black Sea coast six months ago. Ivan says he used to meet other men on the dance floor, but says that the venue’s security guards nowadays make sure that two people of the same sex don’t hug or kiss each other.

“You can only give people a quick hug now, like when saying hello. No way can you kiss! I’ve already been told off once for kissing a guy,” Ivan complains. “I don’t want to get a second warning or I’ll be barred.” To avoid that happening, Ivan says he now arrives earlier, before the show starts, to meet guys at the bar.

“Raids are fucked up!” Ivan says when I ask him if he’s ever been caught up in one, though he explains that while he’s never experienced one himself, a good friend once did. “People in masks came storming in, and screamed, ‘Everybody get down on the floor!’ — he was holding a bottle of beer that got smashed as he tried to get down on the floor, and he was cut by a shard of glass. He asked the cops if he could move, but they told him to stay where he was, in a puddle of liquid and shards of glass, all the while calling him a faggot and other awful terms.”

I ask Ivan if he’s scared to go to clubs now, but he answers morosely that he is more upset by the management’s decision to ban drag performances. However, he muses, “now Trump is back in power, Russia will soon make peace with everyone, sanctions will be lifted and drag will come back”.

The smoking room

I decide to go for a cigarette. There are about 10 people in the smoking room, waiting for the show to start. I ask a woman and man in the corner for a light and we get talking.

“Have you been here since the raids?” I ask.

“I’ve already been told off once for kissing a guy. I don’t want to get a second warning or I’ll be barred.”

“No, this is our first time in a year,” the young man replies. “My boyfriend comes here regularly.”

“Why, were they very rough?” the woman asks. “I read something about it, but I didn’t think it was that bad.”

“They were face down on the floor for four hours!” he explains. “Inferno shut down altogether. My boyfriend now tries to leave clubs before 6am. He says that according to police procedure, raids only happen after 6am.”

Though I don’t want to worry them, I do nevertheless tell them that in most cases, the security forces don’t wait until morning and that raids often happen earlier than that. The young man throws his hands up in the air in response.

“Did you see the military recruitment poster at the entrance?” the woman asks, turning to me. “My friends and I joke that this is now a pro-war straight club.”

Lip service

“Welcome to our cabaret!” the compère cries out. “Tonight you will enjoy a five-part show. Though please be reminded that we have a strict no photo, no video policy.”

The velvet curtains open, and a man in high heels and a sequined suit comes out onto the stage. It takes me a minute to realise it’s Zaza Napoli.

“Is that Zaza?” I ask a woman in front of me as I try to shout over the music. “I can’t tell without the make-up and clothes.”

“The management never saw us as stars, just regular staff, like bartenders and bouncers. So drag coming to an end was no great loss for them.”

“It is!” she shouts back at me. “Doesn’t she look even gayer now than in make-up?”

“The need to change look and to adapt to certain gender stereotypes came in in March of last year,” Nicky Jamm tells me later. “So we had to start performing as males.”

Illustration: Alisa Krasnikova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

For many club owners, queer venues were “first and foremost a business”, and not an attempt to create a space for the LGBT community, according to Nicky Jamm. “When they started out, the gay club niche was free. Clubs weren’t all that nice to drag artists as it was. The management never saw us as stars, just regular staff, like bartenders and bouncers. So drag coming to an end was no great loss for them.”

Kazantsev lip-syncs to a song by Russian superstar Filipp Kirkorov, which a female couple dances along to. Next, another man in a bright suit comes onto the stage and lip-syncs to a song by Russian singer Zivert, and everyone on the dance floor sings along with him.

When the song ends, the crowd starts chanting the performer’s drag name. He smiles indulgently, but the host butts in immediately, insistently repeating his male name. For now, it seems, the only way for queer people in Russia to exist today requires a retreat into the closet.

*Names have been changed.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]