Under a regime that brooks no dissent, communication between activists is one of the most important tools of resistance. Meet the Russian dissidents working to counter censorship through letters, encrypted chats, and secure platforms, and who are shaping networks to ensure that the lines of communication between those inside and outside Russia are maintained.

Silent messages

“Just a few days ago, a journalist was poisoned, not that far from where I live,” says Denis, a Russian journalist and activist in exile. “Sadly, I wasn’t even surprised. Ever since we arrived in Georgia, rumours have circulated about undercover Russian agents monitoring our activities.”

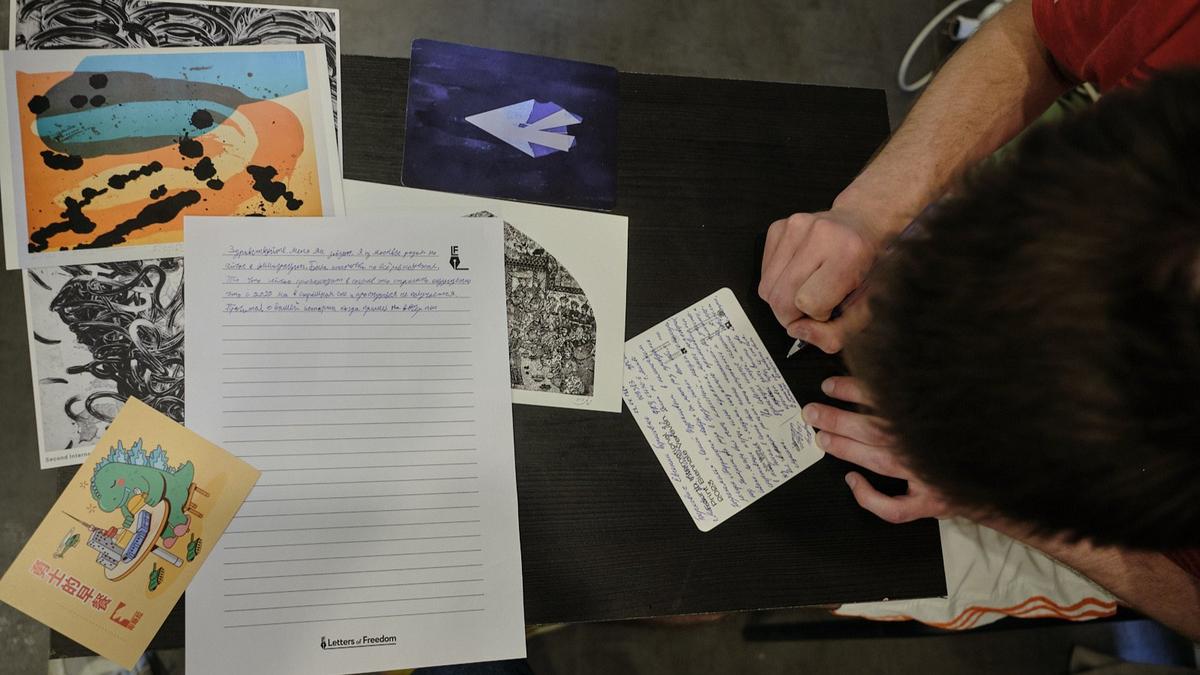

Before fleeing to the Georgian capital Tbilisi to escape conscription, Denis worked for late opposition leader Alexey Navalny’s political campaign in St. Petersburg. Now in exile, he organises events at which former political prisoners in Russia are invited to share their stories with an audience, who also write letters to those behind bars today.

“When we write these letters, we have to be extremely careful to avoid censorship and ensure the message gets through,” Denis explains, sketching a small bear on one of the letters. “Even a simple drawing, seemingly meaningless, can offer a glimmer of hope to political prisoners.”

A volunteer at a food and medicine distribution centre run by Volunteers Tbilisi, in Tbilisi, Georgia, August 2023. Photo: Fabio Lovati

Letters from the outside world remain one of the few remaining direct lines of communication for those thrown into Russian prisons. In many cases, however, letters don’t reach their intended recipients at all, or they arrive with sections of text redacted. To bypass the censor, volunteers have developed creative strategies such as the use of coded language, the addition of seemingly innocent drawings that are actually messages of support, and sending postcards, which for some reason tend to get delivered to prisoners more easily.

“Maintaining communication with those still in Russia is crucial,” Denis continues. “It’s difficult, but I believe that strengthening this dialogue is one of the few ways we can respond to a situation that is becoming more dire by the day.”

Bridges of support

“In a rapidly changing context, dialogue is of the utmost importance,” says Darina, the coordinator of the Kovcheg project in Armenia, one of the most important support networks set up for anti-war Russians and those fleeing the country for political reasons.

When Darina, a vocal war critic herself, left Russia in March 2022, she didn’t realise how widespread the need for expression and connection would become to her fellow exiles in similar situations. Starting as just a small group of volunteers, Kovcheg soon found itself overwhelmed by the thousands of requests it received from newly arrived Russian exiles. Since then, it has become the largest volunteer network assisting anti-war Russians both in exile and at home in Russia.

Darina Mayatskaya, coordinator of Kovcheg, in Armenia, in her workspace in Yerevan, Armenia, June 2024. Photo: Fabio Lovati

Operating across multiple countries, Kovcheg provides legal assistance, psychological support, and even English classes to help new arrivals integrate, and it also helps to prepare those still living in Russia for a move abroad.

“For those still in Russia, we offer webinars on legal rights in political cases, as well as mental health support groups,” Darina explains. “Obviously, we can’t organise in-person events inside Russia, but our online initiatives are open to anyone, no matter where they are.”

Despite the ever-tightening grip of state censorship, avenues of communication between exiles and those inside Russia still exist. Many dissidents rely on encrypted messaging apps such as Signal or Session to evade surveillance, though for most, Telegram remains the primary channel for sharing information that’s not easily available via other outlets in Russia.

Co-chair of Memorial Oleg Orlov discusses his imprisonment in Russia in Berlin, Germany, August 2024. Photo: Fabio Lovati

Through these platforms, Kovcheg has not only provided assistance but has also fostered political discourse. One of its most ambitious programmes, First Flight, prepares Russians — both in exile and at home — to engage in politics and civil society and fosters discussions on how to bring a post-Putin democratic future for Russia into being.

“Many people want to talk, but they’re afraid,” Darina says. “They read our messages, they follow us, but they can’t interact. One wrong word, and they risk years in prison.”

Democracy lab

Given Russia’s sheer size and the diversity of political and social currents within it, opposition movements in the country have a tendency to be diffuse, often operating in diverse and decentralised forms.

While diversity can be a strength, it also complicates the process of forming a unified political identity and a shared strategy for the future. How to bring together the famously argument-prone Russian opposition became one of the dominant topics of debate in the aftermath of Alexey Navalny’s death last year, but differences and rivalries within the movement nevertheless continue to hinder its broader cohesion and coordination.

‘The very concept of democratic opposition is a challenge for those who grew up in Russia, where democracy has remained an abstract idea for over 20 years.’

Aware of this challenge, a network of activists came together in 2022 to create Platforma, an alliance aimed at uniting opposition groups around a few core principles, chief among them ending the war in Ukraine and bringing a democratic post-Putin Russia into being.

“We’ve connected more than 80 organisations, media outlets and activists, but coordination is tough. We have different backgrounds, different visions, and even conflicting ideas about what democracy means,” says Pasha, one of the founders, who moved to Berlin on a scholarship shortly before the Russian invasion of Ukraine three years ago. Unable to return home due to his anti-Putin and anti-war activism, he now dedicates himself full-time to activism.

Platforma operates using a horizontal approach to decision making rather than a hierarchical one, and its core tenet is a belief in non-violence. “We are not an armed group, nor do we support the use of force. However, the very concept of democratic opposition is a challenge for those who grew up in Russia, where democracy has remained an abstract idea for over 20 years”.

As well as its role coordinating different strands of the opposition, Platforma works to develop democratic learning spaces, in which those from different cultural and political backgrounds work together — often for the first time — in non-hierarchical structures that are designed to build consensus and mutual respect.

The Reforum Space, created by the Free Russia Foundation, in Berlin, Germany, August 2024. Photo: Fabio Lovati

Another important aspect of Platforma’s work is its connection with the remaining elements of civil society inside Russia, where — despite the repression — many Russians continue to engage in various forms of nonviolent resistance. “We are in constant contact with groups in Russia, but the crackdown makes everything more difficult. Some of our members have had to flee, while others remain in the country, working at immense personal risk,” Pasha explains.

The network also acts to counter Kremlin propaganda by disseminating independent information, and regularly launches awareness campaigns on various issues aimed at both exiled Russians and those still inside the country.

“We have to think long term. It’s not just about resisting the current regime: it’s about imagining and building a post-authoritarian Russia,” Pasha says.

Leave nobody behind

In Russia, where both censorship and the repression of minority groups have intensified in the past three years, clandestine support networks have formed to assist members of the country’s LGBTQ+ community. These networks provide legal aid, logistical support for those who need to flee the country, and safe spaces for those in danger.

The growing criminalisation of queer identities, which culminated in Russia’s Supreme Court branding “the international LGBT movement” an “extremist organisation” in November 2023, has transformed what was once simply a fight for equal rights into a struggle to stay alive.

Maxim, the coordinator of Centre T, at home in Yerevan, Armenia, June 2024. Photo: Fabio Lovati

“For many queer people in Russia, fleeing was not a political choice but a necessity to survive,” says Maxim, a transgender activist. “If I had stayed, I would have been arrested for LGBTQ+ propaganda or for associating with an extremist organisation”. Indeed, after new laws were passed in 2023, Maxim and his team were forced to shut down a shelter they had been running in Moscow. “We provided refuge to hundreds of people in danger. But with the crackdown, we had no way to operate safely anymore. We had to flee ourselves”.

Once in Armenia, Maxim decided to help other queer exiles as well as those still in Russia, and was soon made the project’s director. “I want to strengthen our global network more and more, in order to provide peer support for trans people, to evacuate individuals and assist them in seeking asylum.”

“We’ve built a support system for those fleeing, offering psychological support and temporary housing for those arriving with nothing,” he explains. “The repression doesn’t stop, so neither will we.”

Yet, even in exile, threats persist. Russian intelligence agencies closely monitor what activists get up to abroad, while queer communities in exile face new forms of discrimination and precarity. As the Russian government tightens its grip domestically, Maxim’s network continues to grow, forging new lifelines for those who can never go back. “Our goal is to ensure that no one is left alone”.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]