The Trump administration’s ruthless plan to strip the almost a quarter of a million Ukrainians who currently live in the United States of their refugee status has once again raised the question of what will happen to the millions of Ukrainians who fled to the European Union when the Russians invaded three years ago.

Studies show that as the war continues, the number of Ukrainian refugees living in the EU who want to remain in Europe after the war is increasing. The reasons for this range from Ukraine’s war-shattered economy and its traumatised population to the prospect of having to start life all over again having adapted to life in a foreign country. Novaya Europe spoke to Ukrainian refugees in the EU about their future and the tough choices they may soon have to face.

‘Every day is a struggle’

Yulia, now 24, left the central Ukrainian city of Poltava with her young daughter in March 2022. She headed for Germany, as her brother already lived there, and spent the first couple of months staying with his friends before she found a home of her own.

A European Commission directive stipulated that all Ukrainians fleeing the war were entitled to temporary protection in the EU, which granted them a residence permit, the right to work, and access to medical care, social security and education across the EU, even though the level of assistance varied from country to country.

By the end of 2024, almost 4.3 million citizens of Ukraine had been granted temporary protection by EU countries. Germany had the highest number, at over 1 million, about 27% of the total in Europe. Poland took close to 1 million, or 23%, while Czechia took the third highest number, at over 380,000, or 9% of Ukrainian refugees in the EU.

“I didn’t know what to do when I came here,” Yulia admits. The state support she received in Germany — €500–560 per month for an adult plus a housing subsidy — meant she didn’t immediately have to work. But within a month, Yulia was taking a government-provided integration course, where she began to learn German. After six months of daily classes, she could communicate with and understand native speakers. When her daughter went to school, Yulia decided to apply to the Ausbildung program, which gave her vocational training paid for by her employer.

Volunteers meet Ukrainian refugees at Berlin’s Central Station, 2 March 2022. Photo: Clemens Bilan / EPA

“I spend two days a week studying and three working in a clinic. … While I’m studying, I receive about a third of the regular salary of a doctor’s assistant, but that depends on the job,” says Yulia. As that income is not enough for her and her child to live on fully, the state helps cover the rent. Yulia says she finds studying and mastering huge amounts of information in a foreign language difficult.

‘Even knowing the language is no guarantee’

Ihor*, 50, also found things difficult after leaving Ukraine. At the start of the war, he was in an area of the Kharkiv region that was occupied by the Russian army, so he could only leave Ukraine via Russia. Ihor had previously worked in Russia, and friends got in touch and offered help. Upon discovering that the Baltic States were closing their borders to Russians, he decided to go to Finland. Volunteers in Helsinki helped him with paperwork and advised him to go to a refugee reception centre.

At first, he was sent to the small Finnish town of Salo, after which he moved closer to Helsinki. But he soon realised that it was difficult to find work both in a small town and closer to the capital.

Knowing the language and how prevalent English is in the host country is a crucial factor when it comes to integration. The authors of a report released by the Institute for Employment Research in the German city of Nuremberg found that Ukrainians who spoke English were able to find work relatively quickly in countries such as Denmark and the Netherlands, where a very large percentage of the population speaks English.

Protesters gather for an anti-war demonstration in central Helsinki, Finland, on 26 February 2022. Photo: Marina Takimoto / SOPA Images / Sipa USA / Vida Press

According to Panu Poutvaara, the director of the ifo Centre for Migration and Development Economics in Munich, most refugees now attend A2 and B1-level language courses, which has had a positive effect. About 80% of Ukrainian refugees in Germany did not speak German when they arrived, but that figure has now dropped to 10%, increasing their chances of finding employment.

Ihor tried to learn Finnish, but was unsure how useful his efforts would be in Finland. “In addition to the language being fairly difficult, there are very few jobs. It’s basically cleaning, construction, and care work,” he says. “Even knowing the language is no guarantee of finding a job. Of course I want to go home, but at the moment I have nowhere to go. … The Ukraine I used to live in no longer exists.”

Ukrainian refugees queue for information at a job fair, Berlin, 2 June 2022. Photo: John MacDougall / AFP / Scanpix / LETA

Admission strategies

Employment rates among Ukrainian refugees in Europe vary significantly from country to country. By the end of last year, about 60% of Ukrainian refugees in the Netherlands had found employment, while that figure was between 55% and 65% in Poland, 57% in Lithuania, 53% in Denmark, and about 30% in Germany. The ability to integrate is not the sole factor determining the likelihood of employment, of course — the peculiarities of the local labour market, current economic conditions and each country’s own policy towards Ukrainian refugees all play an important role.

In Germany, the employment rate is lower, but conditions are better because the country is banking on long-term integration.

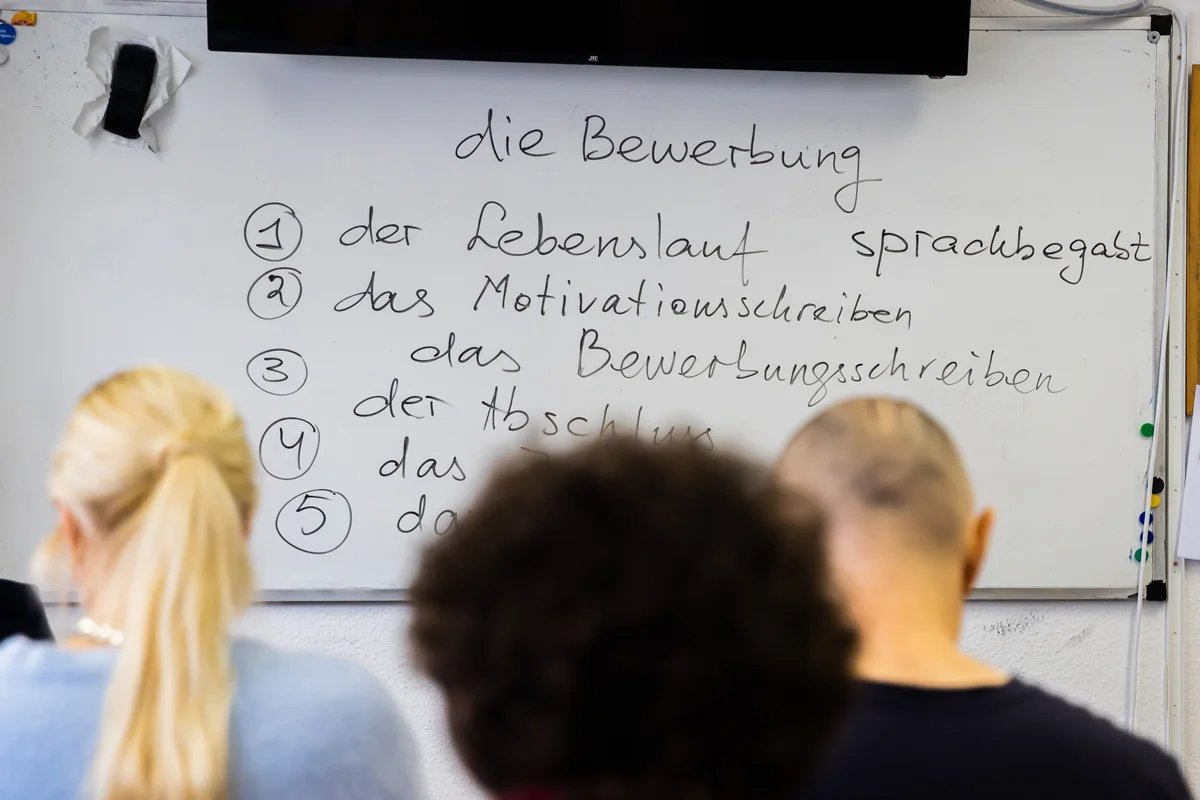

A German lesson at a Berlin language school, 9 November 2023. Photo: Christoph Soeder / dpa / picture-alliance / Scanpix / LETA

However, as Yulia Kosyakova, a sociologist and professor at the University of Bamberg in Germany, observes, giving refugees assistance isn’t simply a matter of profit or loss for the host country.

“Once people are here, it makes sense … to integrate them into the local labour market. Being socially involved and having a job reduces dependence on the state. Even if some people do return to Ukraine, they will return with new knowledge and language skills which will help as the country rebuilds.”

Kosyakova also stresses that integration will improve over time, noting that 16% of Ukrainians were working in Germany within six months, which is higher than that recorded for refugees from other countries.

“But we see integration into the labour market improves over time. After six years, more than 50% of refugees from Syria were working. After seven years, it was more than 60%, and after eight years, about 70%. We expect to see the same thing with Ukrainians,” she says.

Ukrainian refugees arrive at the railway station in Przemyśl, Poland, 17 March 2022. Photo: Darek Delmanowicz / EPA

Repeat trauma

In March 2024, Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal proposed redirecting funds currently used to support Ukrainian refugees in the EU to developing programs to support refugees wanting to return to Ukraine. One adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, Serhiy Leshchenko, even suggested withdrawing support for Ukrainian refugees in the EU altogether in order to get them to return.

According to the ifo, the majority of Ukrainians currently living in the EU plan to return home eventually. But the number of refugees intending to remain outside Ukraine is gradually increasing and had reached 25% by mid-2024.

The Ukrainian government has endlessly repeated how important it will be for refugees to return home to play their role in rebuilding the shattered country once the war ends. However, Kosyakova warns that returning, especially if done under duress, could be hugely stressful for people whose lives had just begun to stabilise after fleeing the Russian invasion.

Yulia says she can’t imagine returning home, having put in too much effort into building her new life to “just give up”. Since the war began, her sense of duty has shifted from one towards her homeland to one focused more on herself, she says.

‘Don’t they want us to stay here?’

Economic considerations are another factor affecting refugees and their desire to return to Ukraine. After the invasion, inflation in Ukraine rose sharply from 10% in 2021 to 26.6% in 2022. Last month, the rate stood at close to 13%.

“Czechia clearly only wants the middle class to stay, like the IT specialists, but they only make up about 5–7% of refugees.”

Maksym* has been living in Czechia on a temporary protection visa for almost three years now, and says that he has fully adapted to life in the country. He found a job almost immediately after arriving in Prague, where he attended language courses for six months. He says he’s concerned by the high prices and the poor economic prospects that would await him if he returned to Ukraine.

“It’s not usually a problem for Ukrainians to find a job in Czechia, because there are a lot of agencies that can find you work at factories, in warehouses or on building sites. They take a 10-20% cut, but they help with job referrals and paying taxes. Probably a good 80% of people first find work through agencies when they arrive,” Maksym says.

A rally on Charles Bridge on the third anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Prague, Czechia, 23 February 2025. Photo: Eva Korinkova / Reuters / Scanpix / LETA

According to the most recent data, over 120,000 Ukrainian refugees have found work in the country, making them net contributors to the state budget. Even in 2022, about 25% of Ukrainian refugees said they spoke Czech at a level where they could communicate effectively in everyday situations.

Ukrainians in Czechia who had received temporary protection status could not previously change the purpose of their stay in the country, but a recent change in the law means they can now switch to a long-term residence permit and stay in the country when the war ends. However, the applicant must first prove that they are financially independent and have a gross annual income of at least 440,000 Czech crowns (€17,500).

However, according to Maksym, the average monthly salary of an ordinary warehouse or factory worker is between 34,000–35,000 crowns (€1,350–€1,400), leaving them short of that threshold.

“Czechia clearly only wants the middle class to stay, like the IT specialists, but they only make up about 5–7% of refugees,” Maksym says, adding that it’s unclear what alternatives those who don’t meet the minimum income requirements might have. Nevertheless, he says he has no intention of returning to Ukraine when the war ends.

*Names have been changed