A law due to come into force in April will see Russia take a tough stance on the enrolment of migrant children in schools, barring access to those who fail a Russian language test and potentially threatening their parents with deportation.

In December, Russia’s State Duma passed a bill making it mandatory for the children of migrants to pass a Russian language test before enrolling in school, and providing for the involvement of Russian social services should any child who fails the test not then attend a mandatory three-month language course that they are liable to pay for.

The authorities have made no announcement of how much these language courses will cost, how parents can enrol their child, or where they will be made available, but a 16-week online Russian language course at St. Petersburg State University costs 14,370 rubles (€149), a price that may well prove prohibitive for many families without a stable source of income.

Human rights advocates have condemned the new measure as unconstitutional, arguing that it violates the right to education. Stefania Kulaeva, who heads the Brussels-based Memorial Anti-Discrimination Centre, which advocates for the rights of minorities in the former Soviet Union, not only does the new legislation complement the Kremlin’s increasingly xenophobic rhetoric, it’s also likely to further isolate migrant families and discourage parents from enrolling their children in school for fear of deportation.

Russia has been tightening immigration legislation since the deadly terror attack on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall in March, in which 14 of the 15 suspected perpetrators were from Tajikistan. Shortly after the attack, the Russian authorities set up a registry of illegal migrants and authority to deport migrants who had committed even minor offenses was handed to the police.

“It appears as if schools are being asked to double as border control, as they are required to check documents presented by migrant children.”

While human rights activist Valentina Chupik agrees that the new initiative violates the Russian Constitution, she says it would likely only affect a “negligible” number of families because “there are simply not many school-age migrant children in Russia” — only around 8,000, as many migrant families end up receiving Russian citizenship.

Nevertheless, this is not the first time that Russia has scapegoated migrant children by restricting their access to education. In September, the Education Ministry recommended that a class should have a maximum of three students who are not proficient in Russian for more “effective learning”. However, this measure only applied to children who don’t have Russian citizenship, as the government failed to distinguish between migrant children and Russian citizens who are not proficient in Russian.

A sign reading “school is a land of knowledge” hangs on a classroom door at a school in St. Petersburg. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov

Even before 2024, it was becoming increasingly difficult for migrants to enrol their children in schools in Russia, as despite violating a 2015 Supreme Court ruling that stated a child’s birth certificate was sufficient to enrol them, schools consistently request numerous documents that not all parents had — including a child’s registration at their place of residence, medical certificates, and confirmation of the child’s right to live in Russia.

According to Chupik, schools have always required additional documents from migrant children and challenges enrolling migrant children in schools are nothing new, with many missing out on formal education for months at a time. The only difference is that these once irregular practices have now been “legalised”, Chupik added.

“There are millions of Russian-born children who do not speak Russian as a native language. Many of them speak Russian poorly but the law is only aimed at a tiny fraction of children

According to a 2017 study conducted by Moscow’s Higher School of Economics that analysed eight schools near Moscow, migrant children often ended up at less prestigious or underperforming schools and were often placed in classes alongside children with learning disabilities. The same study also found that “overcrowding” was used by some schools as a pretext for refusing to enrol migrant children, while others would require children to complete a Russian language proficiency test even before they were mandatory, or they would delay enrolment by asking for additional documents, which one principal of a Moscow school called “a necessary measure”.

Forcing children to undergo language proficiency tests adds an extra barrier to education for migrant children, as in many cases their parents ultimately decide to avoid administrative difficulties and let their children stay at home instead. In other cases, children have become so overwhelmed that they chose to stop attending school themselves.

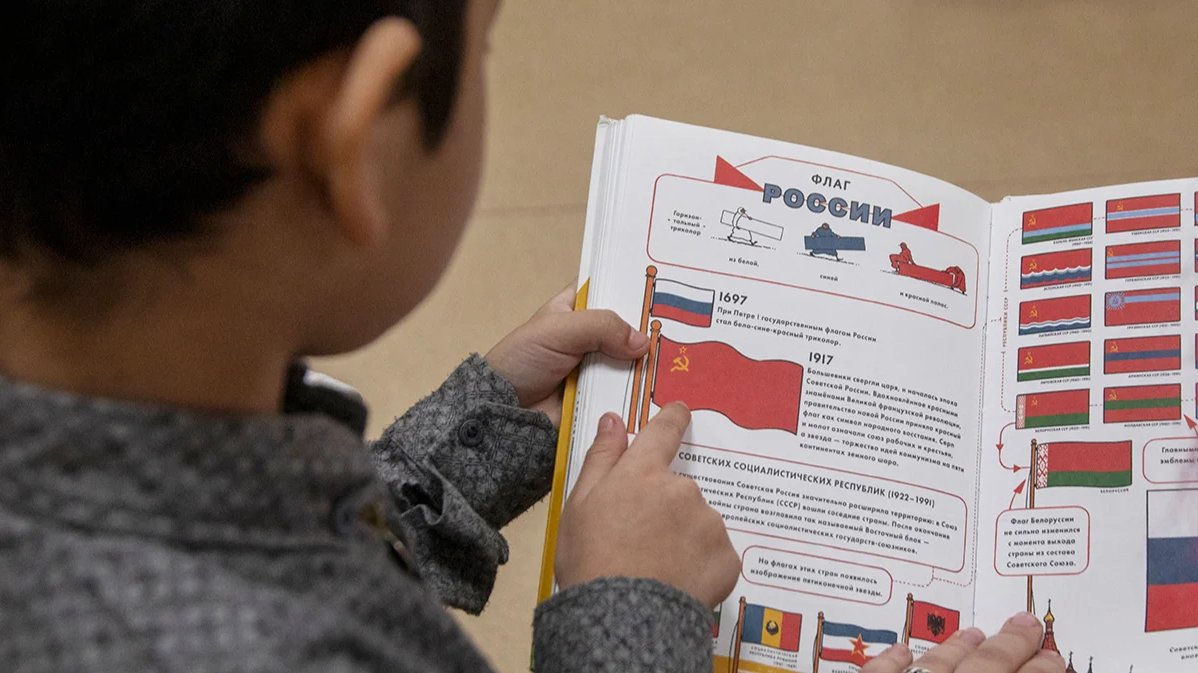

A young pupil at a centre for immigrants in St. Petersburg. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov

The HSE study highlighted one case in which an 11-year-old girl from Kyrgyzstan who had been living in Russia for almost a year was found not to have been enrolled in a school and had instead been staying at home to look after her younger sister.

According to Kulaeva, mandatory Russian language tests will worsen this already serious issue, — migrant children will either remain at home, or their parents will be forced to buy forged documents, which will also put them at risk of deportation if they are caught.

Russian teachers have become divided over the new regulations, with some supporting the new measure, sharing the same xenophobic sentiments as the authorities, while many are concerned that the regulations will only incite hostility.

Those in favour argue that children who do not know Russian interfere with the education of others in the classroom and, according to Yaroslav Nilov, a member of the right-wing populist Liberal Democratic Party of Russia who co-authored the bill, “prevent Russian children from learning the curriculum properly.”

However, according to a study conducted by the Institute for Applied Economic Research at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, the vast majority of teachers believe that migrant children have no problems learning (80%) or communicating with their peers (70%).

Indeed, many teachers appear unsure why the new criteria only apply to non-Russians, given the large number of ethnic minorities in the country whose native language is not Russian. One Moscow teacher who wished to remain anonymous said that there were “millions of Russian-born children who do not speak Russian as a native language. Many of them speak Russian poorly but the law is only aimed at a tiny fraction of children.”

Some teachers also reported that primary school-aged children who don’t know Russian had no problem adapting and learning a new language quickly. One major concern about the legislation is the lack of teachers in Russia qualified to teach Russian as a foreign language.

“It appears as if schools are being asked to double as border control, as they are required to check documents presented by migrant children,” one teacher told Novaya Gazeta Europe on condition of anonymity, adding that such measures would only serve to provoke segregation and prejudice not seen in Russia since the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. “I hope this won’t become a mass occurrence”, she added.