The meeting in Saudi Arabia between senior delegations from the United States and Russia could be the first step towards an end to the war in Ukraine — and not just an end to the war. In almost five hours of talks, US and Russian representatives reportedly agreed to work on both a peace settlement and to explore economic and investment opportunities that could result from it.

James Rodgers

Reader in International Journalism, University of London

Whatever the final outcome, Ukraine seems set to lose out.

The same cannot be said of the long-term occupant of the Kremlin. For 20 years, Vladimir Putin has been working towards what US President Donald Trump has now given him. Ever since Putin bemoaned the collapse of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century, his foreign policy has been about getting back at least some of the superpower status the Soviet Union enjoyed.

In one sense, Trump’s overture to Putin to discuss peace in Ukraine has given the Russian leader exactly what he wanted: for Moscow to be respected — and perhaps even feared — by the West in the same way the Soviet Union once was.

In that sense, Trump’s telephone call with the Kremlin represented a huge triumph for Putin, who now has a pending invitation to return to the top table of world affairs without conceding an inch of occupied Ukrainian territory to get there. Nor has he even undertaken to give back any of what Russian forces have seized since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine three years ago.

Now his foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, is talking to the US Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Meanwhile the annexation of Crimea in 2014 — which is when Russia’s war on Ukraine actually began — seems increasingly likely to be overlooked. The suggestion from the US Defence Secretary Pete Hesgeth last week that a return to Ukraine’s pre-2014 borders was “unrealistic” has made clear Washington’s current view on that.

So far, so good for Putin, who sees the Western alliance that has been ranged against him — albeit with varying degrees of enthusiasm and commitment — for the past three years beginning to crack.

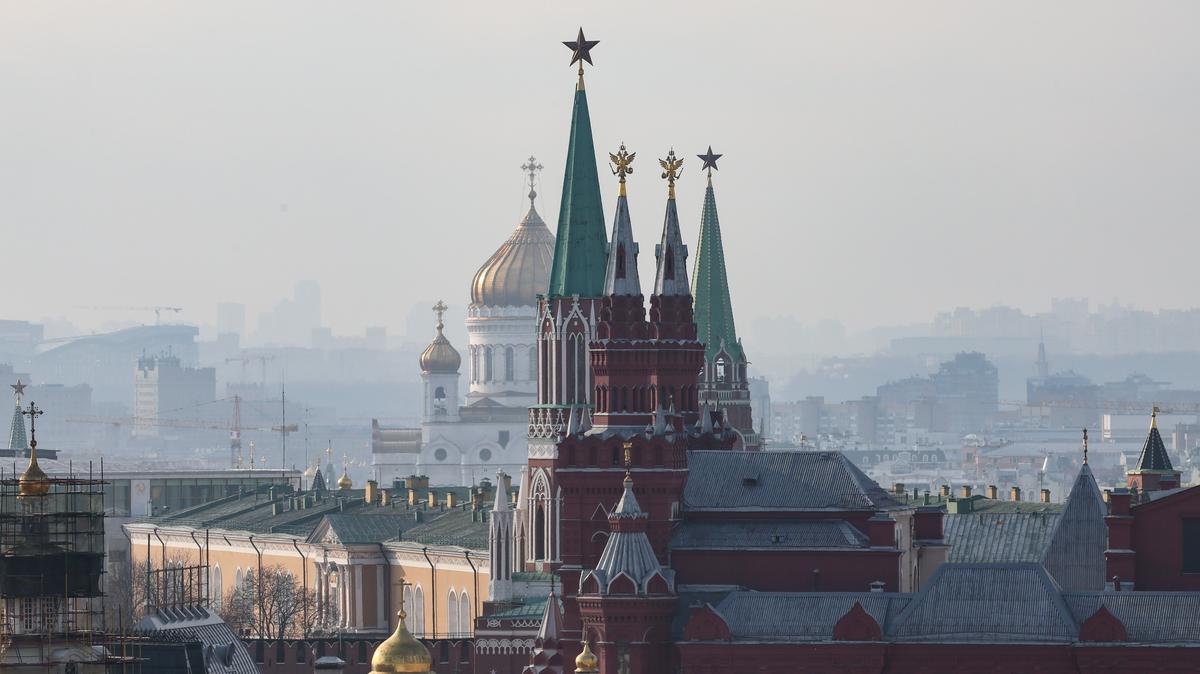

A member of the Russian Communist Party near Red Square in Moscow, 5 December 2024. Photo: EPA-EFE/YURI KOCHETKOV

Under Trump, Washington’s policy on Ukraine is showing signs of significant divergence from that of the EU or UK. Putin no doubt sees his determination not to be cowed by Western pressure as starting now to lead to longer-term success.

Now the two leaders have agreed to meet — a complete reversal of the three years of increasing isolation during Joe Biden’s presidency. And, as we know, the first time the two leaders met for a summit, in Helsinki in 2018, Putin was widely seen as having outwitted Trump. As Trump’s then senior director for European and Russian Affairs, Fiona Hill, recalled in her memoir: “As Trump responded that he believed Putin over his own intelligence analysts, I wanted to end the whole thing.”

Putin will hardly feel he enters any future negotiation as an underdog. Just by being there, to discuss the most pressing matter for the future of European security with the US president, Putin has achieved part of his long-term goal. Just as in the days of the Soviet Union, leaders from the Kremlin and the White House will meet to discuss European affairs as the preeminent powers on the continent.

The views of Europeans themselves, especially Ukrainians, are secondary.

If Putin’s 2005 lament for a lost superpower gave a clue to the course his time at the summit of Russian power would take, then he gave yet more clues on the eve of the full-scale invasion. In December 2021, Putin regretted the collapse of the Soviet Union once again.

This time he said it had a significance far beyond the century in which it happened, saying: “We turned into a completely different country. And what had been built up over 1,000 years was largely lost.”

Days later, with expectations growing that Russia was planning to invade Ukraine, the Foreign Ministry in Moscow published a document it called Treaty between The United States of America and the Russian Federation on security guarantees.

A Just Russia For Truth party member with the letter Z and the inscription "Glory to Russia at all times!" on his sleeve in Moscow, 23 December 2023. Photo: EPA-EFE/YURI KOCHETKOV

The language chosen is striking today for the references it makes to the Soviet Union, as in article 4: “The United States of America shall undertake to prevent further eastward expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and deny accession to the alliance to the states of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.”

The Biden administration dismissed the treaty as the trolling it represented. But Hegseth’s recent remark, “The United States does not believe that NATO membership for Ukraine is a realistic outcome of a negotiated settlement,” fits right in with Putin’s wish list.

This is about Russia becoming the international heavyweight the Soviet Union once was. It is also about a turn of events that greatly favours Putin.

There is nothing to say that Putin’s long view of history won’t encourage him to go to war again in a few years.

For three years, I have been working on a book, The Return of Russia: From Yeltsin to Putin, the Story of a Vengeful Kremlin. My research included interviews with leading policymakers, among them Jens Stoltenberg, who served as secretary general of NATO between 2014 and 2024. When we spoke in September 2023, I took the opportunity to ask him how he saw the coming months in the war in Ukraine.

He told me: “Only the Ukrainians can decide what is an acceptable solution. But the stronger they are on the battlefield, the stronger they will be on the negotiating table and therefore our responsibility is to support them … but it’s for Ukrainians to make the hard decisions on the battlefield. And of course at the end at the negotiating table.”

Trump’s démarche towards a deal appears to ignore that logic, and strengthens Putin’s hand before negotiations have even started.

If it does lead to an end to the war now, there is nothing to say that Putin’s long view of history won’t encourage him to go to war again in a few years. And he’ll be better prepared to capture more territory than he has already in the last three blood-soaked years.

This article was first published by The Conversation. Views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of Novaya Gazeta Europe.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]