Following the recent news that Russia’s Interior Ministry has been considering the creation of a database to track members of Russia’s LGBT community, experts were quick to cast doubt on whether such a move would even be technically possible. Yet the idea is not without precedent — lists of gay people were kept during the Soviet era.

Though they were initially created to track people with sexually transmitted diseases in order to quickly identify chains of infection, the lists focused mainly on homosexuals, sex workers and other persons deemed by the prudish Soviet authorities to be leading “an immoral lifestyle”.

Soviet health ministries resorted to such lists and statistics on more than one occasion, finding them a very effective tool to combat the epidemics of syphilis and gonorrhoea that broke out in the early 1960s.

One such list was mentioned by a Ukrainian Health Ministry official in a 1964 report, which said that Kyiv dermatologists had given the police lists of 235 people thought to lead “promiscuous sex lives” and be “repeated sources of infection”, over 30 of whom were subsequently expelled from the city.

At the time, officials from Odesa’s Health Ministry noted “the high percentage of homosexuals” among syphilis patients, and stressed the importance of examining “this category of people” in dermatological and venereal clinics. As the lists grew, doctors and police officers began to collate information on the lives led by various members of the gay community, and one archive even contains a table describing the professions and occupations of “homosexuals of interest” and how many of them had syphilis.

The police also compiled lists of homosexuals to be used when investigating crimes that they believed were related to the gay community. In interviews with Russian and US human rights activists in the 1990s, many gay men in Moscow said that the police had regularly interrogated them in the 1980s, usually as part of a criminal investigation.

Russian special forces arrest participants at a Pride parade in St. Petersburg, 26 June 2010. Photo: Anatoly Maltsev / EPA

In one episode of Sledstvie Veli, a popular TV show about crime in the Soviet era, presenter Leonid Kanevsky said that whenever a serial killer appeared in a Soviet city, the investigators first interrogated known local homosexuals.

The lists were regularly updated and included each person’s current address, which meant that they could often be called in for questioning “just because”, or “for preventive purposes”, a tactic used to ensure the gay community always felt ill-at-ease.

The KGB took a particular interest in homosexuals too. Interestingly, it preferred not to arrest LGBT people — homosexuality was officially an Interior Ministry matter — but to recruit them, as homosexual agents often appeared in the memoirs of former political prisoners.

Attempts at blackmail and recruitment weren’t restricted to Soviet citizens either — in 1986, a US citizen was detained for having voluntary sexual relations with a Soviet man in a Moscow hotel. The KGB interrogated, blackmailed and tried to recruit him, but he resisted the attempts, and was eventually released.

There were no officially gay venues in the Soviet Union, but there were well-established cruising grounds, including the Catherine Gardens, one of the best-known gay meeting places in Soviet Leningrad. The KGB was well aware of such places and would often sent agents to them.

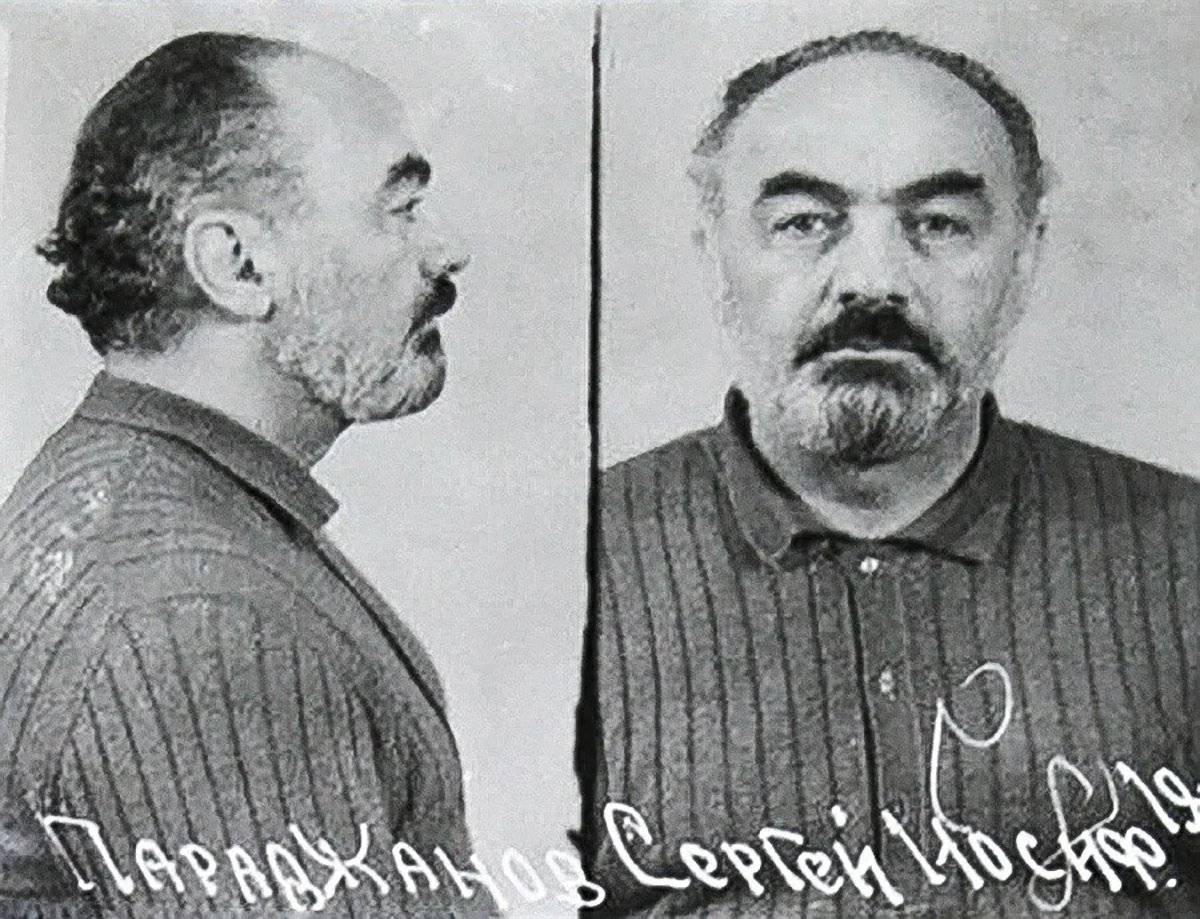

Sergey Parajanov following his arrest by the KGB in 1973. Photo: KGB archive

Soviet celebrities also appeared on the Interior Ministry and KGB lists, both to keep them under control and to prevent them from “defaming” the Soviet regime. Some celebrities were spied on and had trumped up criminal charges brought against them.

In one of the best known cases of the targeted persecution of LGBT people in the Soviet Union, the Interior Ministry and the KGB spied on Tbilisi-based Armenian film director Sergey Parajanov for years as he made some of the country’s most transgressive and original films, including his queer-coded masterpiece, The Colour of Pomegranates, in 1969.

However, due to his nonconformism and anti-Soviet political views, he was eventually arrested in Kyiv in 1973 and charged with sodomy, for which he was sentenced to five years in a brutal prison camp in 1974.

Described by the head of the Ukrainian KGB, Vitaly Fedorchuk, as “someone hostile to Soviet reality” who had made “slanderous remarks” about the suppression of creative freedom in the Soviet Union, Parajanov’s “hostile actions” were ultimately brought to a stop by using case materials collected by the KGB over the year documenting his “immoral lifestyle”.

The cover of Rustam Alexander’s Red Closet: The Hidden History of Gay Oppression in the USSR.

While “LGBT registries” existed in the Soviet Union, there is nevertheless a significant difference between what happened then and what is happening in modern-day Russia. The Soviet law on sodomy was fairly narrow in its interpretation, and the only way to impose a custodial sentence in such cases was by proving that two men had had sex. Try as they might, police officers found it difficult to provide evidence in such cases.

Furthermore, homosexuality was a taboo subject in the USSR and was not discussed on television or in newspapers, making the police and the KGB rather reluctant to pursue such cases.

Modern-day Russia has no law on sodomy, but there is now a broader legal framework for crackdowns, covering not just those in same-sex relationships, but also those who frequent LGBT venues, write social media posts, or work in queer institutions. The potential for ending up on an equivalent modern-day list is endless.

The Soviet Union had no smartphones, whereas now everyone, queer or not, can have “evidence” in their pocket of “involvement” in what the Russian government has deemed to be “the international LGBT movement”. Whereas primitive technology and the taboos of the day worked to some extent in favour of gay people in the Soviet era, the Russian authorities now have greater potential to cast an even wider net against anyone they deem “undesirable” or “extremist”.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]