In disgust at Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Yakut punk musician Aykhal Ammosov defiantly resolved to display a banner reading “Yakutian punk against the war” during a visit by Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin to the city of Yakutsk in Russia's Far East in August 2022.

Ammosov, who had already been fined on three separate occasions for picketing, spraying anti-war graffiti and distributing anti-war leaflets, was later charged with “discrediting” the Russian military for his brave act. After being held in pretrial detention for 42 days, Ammosov was released but slapped with a ban on leaving the country. In desperation, he decided to flee to Belarus, as almost no border checks operate between the two countries, which are technically part of a so-called Union State.

“Yakutia will be free” poster. Fanart: Aykhal Ammosov / Instagram / @eternalwinter22

Though he initially planned to enter the EU illegally by swimming across the river that forms the border between Belarus and Poland, Ammosov later told media outlet No Future that he had ultimately abandoned the idea once he’d properly come to understand the risks it would involve.

Instead, he settled on travelling to Kazakhstan, another common destination for Russians seeking to flee the country without attracting undue attention to themselves.

While Ammosov made it to Kazakhstan successfully, he was arrested at the request of the Russian authorities shortly afterwards. Ammosov spoke to Novaya Gazeta Europe about his feelings of fear and despair, his arrests and imprisonment — and how he eventually managed to reach safety in Berlin.

Sakha Punk

Ammosov’s interest in rock music began while he was in school, where he learnt how to play the guitar and started his own band. At 18, Ammosov moved to the regional capital Yakutsk to enrol at the city’s university. Between his studies and odd jobs, he formed Crispy Newspaper, a punk band whose songs in the Yakut language Ammosov describes as “Sakha Punk,” using a regionally preferred adjective for the ethnic group to the more commonly used Yakut. Crispy Newspaper soon joined Youth of the North, a record label and art collective at the centre of the local punk scene.

Following the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Ammosov increasingly had run-ins with the authorities over his anti-war protests.

In 2018, Crispy Newspaper recorded their first EP, Words of Wisdom, and while the band continued to record and perform following the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Ammosov increasingly had run-ins with the authorities over his anti-war protests. He was arrested for picketing outside a funeral supplies store and for distributing leaflets that said, “No to war! Get your hands dirty with paint, not blood!”

After his release from pretrial detention in the fall of 2022, Ammosov began working in a senior care home, where he was one of just three staff responsible for tending to over 50 residents. Members of the local security apparatus would often come by to speak with at work. “They warned me not to attend protests,” he explains.

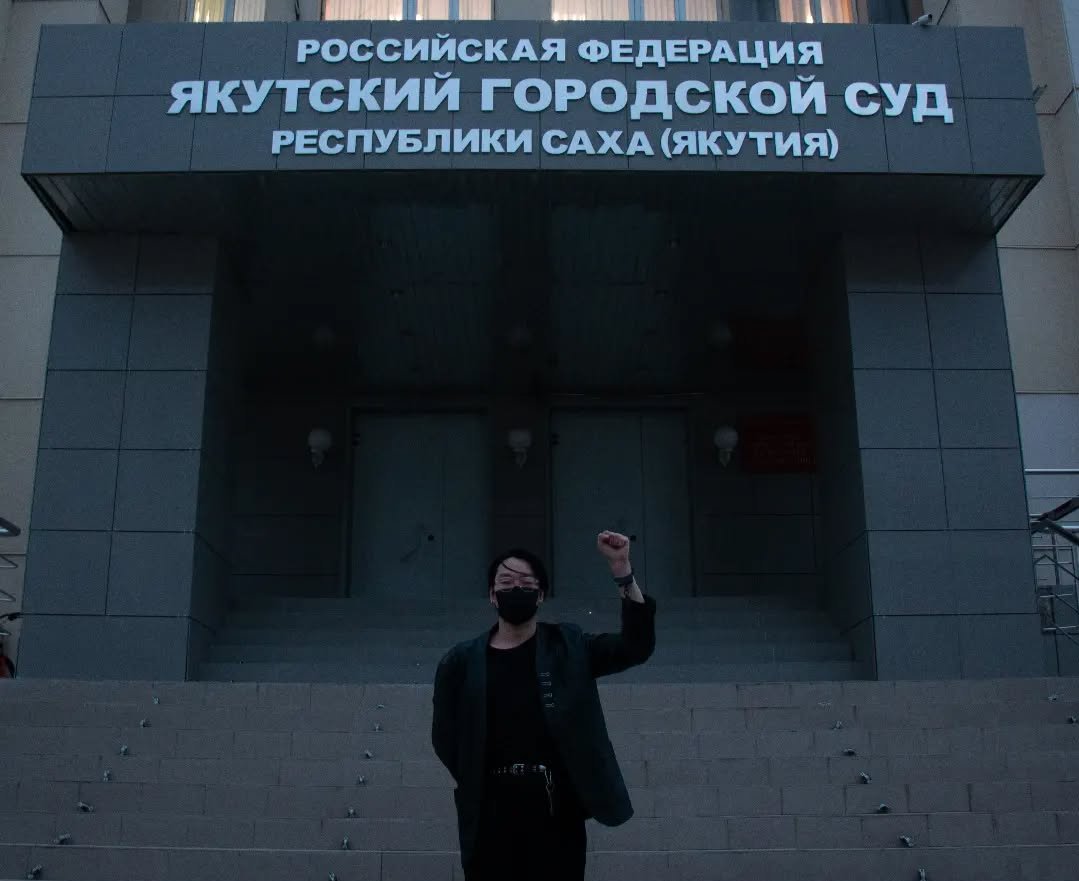

Ammosov in front of the Yakutsk City Court. Photo: Aykhal Ammosov / Instagram / eternalwinter22

In early December 2022, Ammosov decided that it was time for him to leave Russia, though he didn’t tell any of his friends or his family about his plans. It took him two weeks to hitchhike some 8,000 kilometres through Russia to Smolensk. From there, he entered Belarus on foot, crossing a river and snowbanks. From there, he had hoped to illegally make his way into Europe, but soon realised that the plan was too risky, settling instead on travelling to Almaty in Kazakhstan.

“I knew that, sooner or later, they would catch me and put me in jail.”

There he managed to find work as a mover at a furniture store. “While I was deciding where to go next, I was put on an international wanted list. If I tried to leave Kazakhstan, I would’ve immediately been arrested. Human rights activists promised to help me, but it would take some time.”

A year without sunlight

One day at work, after Ammosov finished unloading a 40-tonne truck, he was suddenly detained by plainclothes law enforcement officers working for Kazakhstan’s intelligence agency. “They said they had received orders from Moscow and had to arrest me,” he recalls. Ammosov was then interrogated. “I didn’t try to convince them to let me go. I knew that, sooner or later, they would catch me and put me in jail,” he explains. The law enforcement agents told him that he would be sent to pretrial detention and then extradited to Russia.

But Ammasov’s extradition didn’t go quite as smoothly for Russia as it had hoped, being complicated by the fact that “discrediting the army” isn’t a crime in Kazakhstan, and this became the basis of the appeal mounted to grant Ammosov political asylum.

In the meantime, he was sent to Central Asia’s biggest prison — Almaty Central. “They have everyone there. Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, Russians, Ukrainians, but I was the first one from Yakutia,” he laughs.

Photo: Vitaly Malyshev

However, the conditions were brutal, and as he wasn’t even allowed to go on walks, Ammosov says that he didn’t see the sun for an entire year. He was also prohibited from meeting with his lawyer.

“The cell walls were black from mold, they were unsanitary, with rusty bunks,” Ammosov says, though he admits he made a number of friends there.

Kazakhstan to Berlin

On 9 November 2024, exactly one year after his arrest, Ammosov was suddenly released.

“I had no hope of getting out. I didn’t think I would get that lucky. That day, a guard came in and called my name: ‘Be at the exit in 10 minutes with your belongings.’ I thought it was a joke,” Ammosov recalls. As soon as he was out, he called one of the human rights activists who had supported him during his appeal, before getting in touch with some Azerbaijani friends and making plans to meet up with them.

First, Ammosov decided to meet with human rights activist Bota Sharipzhan from the organisation Wake Up, Kazakhstan. But their chat was cut short by law enforcement who approached Ammosov on the street, saying he “shouldn’t have been released”.

Photo: Vitaly Malyshev

“The human rights activist shouted something, but they shoved me into a car with my bag and took me away,” Ammosov explains. “They handed me over to two Kazakh police officers who then took me to an immigration office.” At one point on the way there, Ammosov’s Azerbaijani friends blocked the police car and invited the officers “to talk”. “We’re taking him, and we don’t give a fuck. Here’s the address if you want to chat,” Ammosov recalls his friends saying. “That’s how they got me out.”

Thanks to the efforts of local human rights activists, Ammosov was able to get a humanitarian visa and a temporary travel document. But his troubles didn’t end there. Despite his release from prison, he was still wanted by the Russian authorities.

“[Kazakh police] detained me at the airport and took me to a police station, where we argued for three hours,” he says. “At first they didn’t want to let me leave the country. They insisted they couldn’t let me go so easily. They were ordered to detain anyone on the wanted list.”

However, with the help of human rights activist Gulmira Kuatbekova, who works for the Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights, Ammosov was able to get permission from the Kazakh authorities to leave for a third country. Kuatbekova convinced them that Ammosov couldn’t be imprisoned because he had been granted political asylum in Germany. “They called their bosses, asking them what to do,” recalls Ammosov. “We fought hard and they eventually let me leave. I almost missed my flight.”

Ammosov finally made it to Berlin, which he still feels was something of a miracle. He’s now living in a dorm and plans to look for a job. “I definitely want to celebrate this New Year’s,” says Ammosov. “Russian anarchists invited me to celebrate with them. They want me to DJ.”