While journalism may never have been a particularly safe profession in Russia, it became virtually illegal after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Since the country’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine almost three years ago the authorities have consistently restricted coverage of certain topics and many journalists have found themselves locked up for simply doing their jobs. Novaya Europe looks at some of those who have found themselves on the wrong side of the law in the past year.

Nadezhda Kevorkova

A respected journalist specialising in the Middle East and North Caucasus, Nadezhda Kevorkova has contributed to Novaya Gazeta and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and her reporting from conflict zones such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Gaza and Syria has been recognised with a nomination for the US State Department’s International Women of Courage Award.

Kevorkova was detained in early May and charged with “justifying terrorism” for two social media posts she made related to her close study of terror organisations, since when she has been in pretrial detention and faces up to five years in prison.

The first post to have drawn the authorities’ ire was a repost of a 2010 article written by Kevorkova’s late friend and colleague Orhan Dzhemal that discussed a 2005 armed raid by a group of Islamist militants on the Russian city of Nalchik in the North Caucasus.

Nadezhda Kevorkova appears in court in Moscow, 22 November 2024. Photo: Alexander Nemenov / AFP / Scanpix / LETA

The second article she posted was about the Taliban, which the authorities claim appeared to justify the group’s activities, despite the fact that the Russian government is currently in the process of removing the Islamist group from its list of terrorist organisations.

Among the journalists covering Kevorkova’s case is her own son, Vasily Polonsky, who on 6 May wrote: “My mum is not guilty of anything; She’s a journalist.”

Journalist Pavel Kanygin has described Kevorkova’s arrest as “another reminder to everyone in Russia how dangerous it is not just to be a journalist, but to be a person with their own opinion”, adding that the continued persecution of journalists — even for opinions expressed years ago — was “a hammer in the sleeve of the regime”.

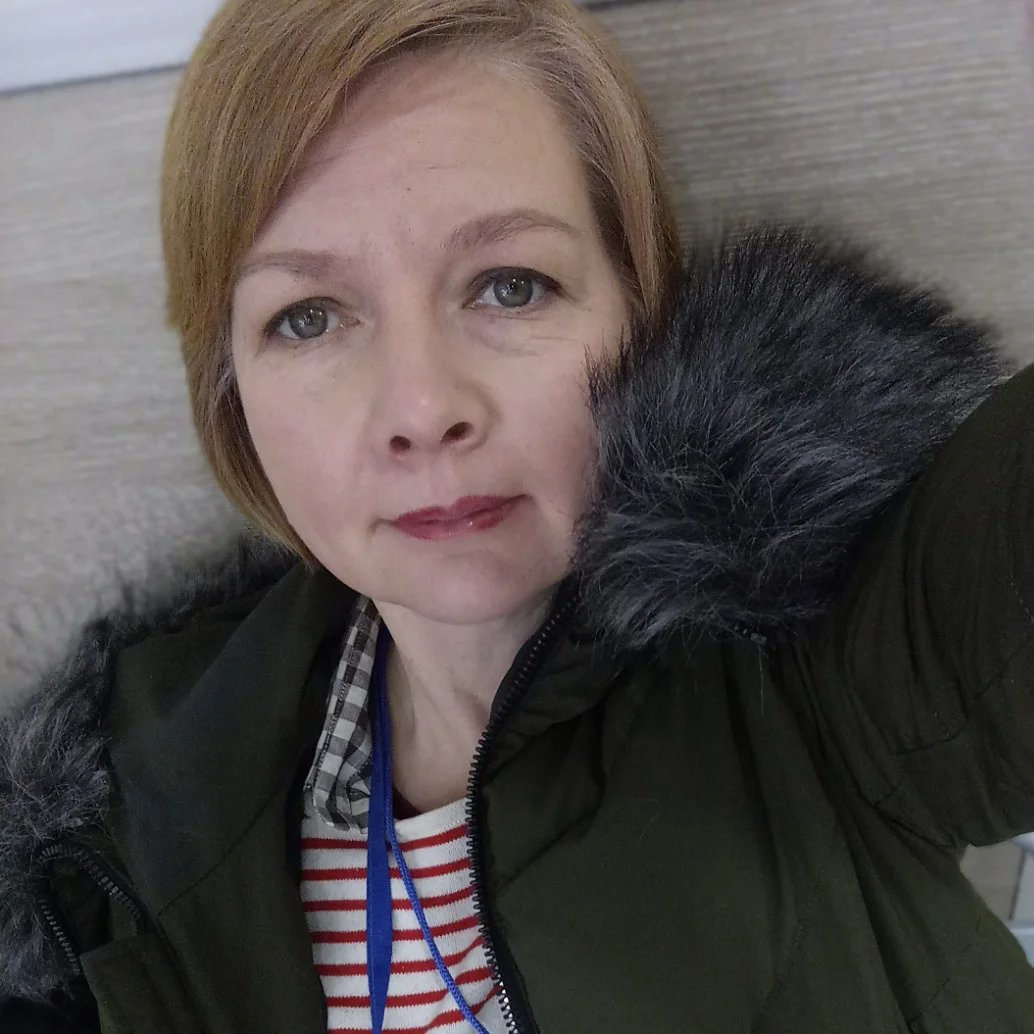

Olga Komleva. Photo: Facebook

Olga Komleva

Activist and journalist for Russian independent news outlet RusNews, Olga Komleva was detained in March for her links to Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), which has been declared an “extremist organisation” for its courageous investigations of corruption in Russia.

Komleva’s involvement with the Anti-Corruption Foundation dates from 2017, when it opened an office in her hometown, Ufa, the capital of the Volga republic of Bashkortostan, and her ties to the organisation served as grounds for her persecution by the state even before the FBK was deemed “extremist”.

Law enforcement officers first searched her apartment in 2019, seizing her laptop and hard drive. It was then searched again in 2021 after Lilia Chanysheva, Navalny’s former chief of staff, was arrested in Ufa.

Since then, Komleva has been repeatedly detained and fined for participating in anti-government and anti-war protests, and has been fined a total of over 6 million rubles (€55,000). In July, prosecutors brought another case against Komleva for disseminating “false information” about the Russian military.

In November she issued an open call to anyone who knew her personally who wanted to show their support by attending her trial to do so, urging them “not to be afraid”. During her time in prison, Komleva has written widely about prison life, often accompanying her accounts with drawings, and always signing off by writing “Olga Komleva, deemed an extremist.”

Antonina Favorskaya

Best known for making the last video recording of Alexey Navalny before his sudden death in prison last year, Antonina Favorskaya is a photo and video journalist working for independent Russian Telegram channel SOTAvision who has also recorded the trials of various other Russian opposition politicians and activists including Ilya Yashin, Vladimir Kara-Murza, Liliya Chanysheva and Oleg Orlov.

Favorskaya was first detained by police in March after she visited Alexey Navalny’s grave at Moscow’s Borisovsky Cemetery, for which she was sent to a special detention centre for 10 days for disobeying police orders.

Upon her release, however, she was again detained and charged with involvement with the FBK, and has been held in pretrial custody ever since.

Antonina Favorskaya appears in court in Moscow, 29 March 2024. Photo: Dmitry Serebryakov / AP Photo / Scanpix / LETA

“Tonya is a serious, professional journalist and she is being persecuted for activities specifically related to her work," SOTAVision founder Alexandra Ageyeva told Current Time TV, a US-funded Russian-language TV channel based in Prague.

Commenting on Favorskaya’s arrest, Navalny’s press secretary Kira Yarmysh noted that “Favorskaya never published anything with the Anti-Corruption Foundation but quite aside from the false accusation, the truth remains: journalists are being prosecuted for doing their jobs. It is not surprising, but still awful.”

According to her family, Favorskaya had never particularly wanted to be a journalist, instead always dreaming of being an actress. Indeed, before the war in Ukraine, Favorskaya studied at the famous Russian Institute of Theatre Arts in Moscow but appears to have moved into journalism following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Confirming her change in priorities, screenwriter Ksenia Novak said that Favorskaya’s photojournalism and activism appeared to be “more of a hobby” and that despite the fact that she had in face been “more interested in an acting career”, since the war started “everything changed”.

Artyom Kriger. Photo: Facebook

Artyom Kriger

Fellow SOTAvision journalist Artyom Kriger is currently in detention awaiting trial for “cooperating with an extremist organisation” over the work he did for the FBK, which included making several videos for the organisation. He has also been accused of using his position at SOTAvision “for conspiratorial purposes”.

Kriger’s family and friends have characterised the case against him as entirely fabricated, with Kriger’s sister Elizaveta even calling the charges “surreal” given that Kriger can hardly be described as a “public figure”. Ageyeva has suggested that Kriger’s case may be connected with Favorskaya’s.

Protest appears to be in Kriger’s blood however, as his uncle, the prominent pro-democracy activist Mikhail Kriger, is currently serving a seven-year prison sentence after being found guilty of “justifying terrorism” in 2023 for a two-year-old social media post that mentioned two violent attacks on regional FSB offices.

Sergey Karelin attends court in Murmansk, 27 April 2024. Photo: AP Photo / Scanpix / LETA

Sergey Karelin and Konstantin Gabov

Sergey Karelin, a reporter who has worked for the Associated Press and German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle, was detained in the Murmansk region in northern Russia in April, the third journalist to have been detained over their work for the FBK, and in Karelin’s case, also for allegedly helping to produce material for the Navalny LIVE YouTube channel.

Though Karelin has said that his arrest came as a total shock to him, he told Novaya Gazeta that while he felt well prepared for prison having previously reported on conditions in Russian penal colonies, he wasn’t so sure how he would cope with not being able to see his daughter and admitted that it was “very hard” to keep his spirits up while being separated from his loved ones.

Konstantin Gabov, a former Reuters producer who was detained by police in Moscow on the same day as Karelin, is also awaiting trial for “cooperating with an extremist organisation” over his past work for the FBK. Like Karelin, Gabov stands accused of helping to produce content for Navalny LIVE and has been in police custody since his arrest.

In October, the court ruled that the trial of all four journalists accused of collaborating with the FBK should be held behind closed doors, meaning that neither family members nor reporters will be able to attend the proceedings.

Konstantin Gabov attends court in Moscow, 25 June 2024. Photo: Yulia Morozova / Reuters / Scanpix / LETA

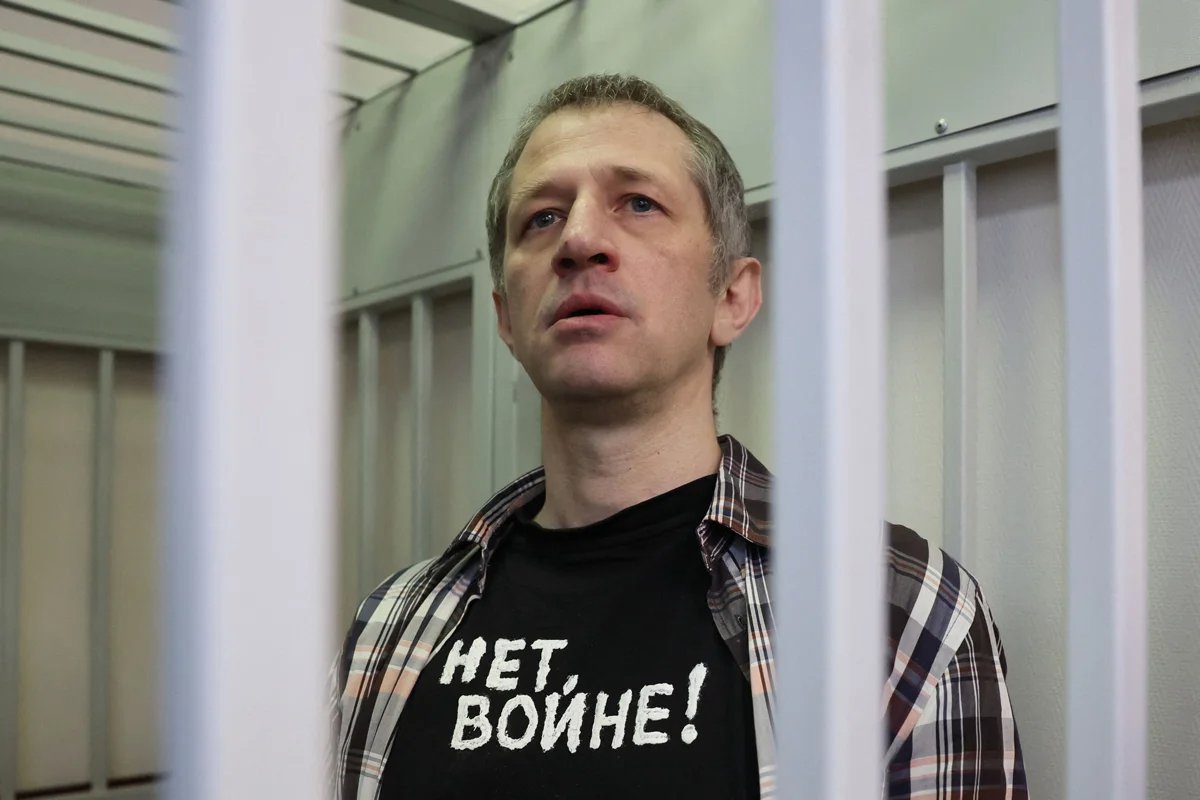

Roman Ivanov wears a “No to War” t-shirt in court in Korolyov, Moscow region, 6 March 2024. Photo: AFP / Scanpix / LETA

Roman Ivanov

After being detained in spring 2023 for three posts in the Chestnoye Korolevskoye Telegram channel — an outlet with just about 2,500 subscribers — Roman Ivanov was sentenced by a court in Moscow to seven years in prison for three counts of disseminating “false information” about the Russian military.

Ivanov remained defiant throughout his trial, and used his final statement to the court to kneel down and make a formal apology to “all the Ukrainians to whom our country has brought grief”.

Sergey Kornilevsky. Photo: biratv.ru

Sergey Kornilevsky

In May, a court in the Russian Far East’s Jewish autonomous region sentenced 61-year-old journalist Sergey Kornilevsky to two and a half years in prison for “justifying terrorism” in a Facebook post he made criticising Russian mobilisation.

Before his case even went to trial, Kornilevsky was added to a list of “terrorists and extremists” by Rosfinmonitoring, the Russian federal agency charged with monitoring the financing of terrorism and money laundering.

Though it’s never been made public which of his private Facebook posts triggered Kornilevsky’s arrest, according to one of his friends, he reposted economic reports that concluded that the war in Ukraine would negatively impact life in Russia, as well as posts about mobilisation.

Prior to his conviction, Kornilevsky worked for the state-owned All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company, where his work covering social and cultural issues was completely unrelated to politics. According to one friend of Kornilevsky’s who spoke to Sibir.Realii, the Siberian affiliate of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, the case is proof that “the hungry censor, prostrate before his superiors, wants to find crumbs” and would “crawl anywhere to find them”.

Nina Novak. Photo: VK

Nika Novak

Nika Novak, a journalist from the city of Chita in Russia’s Far East, was sentenced to four years in prison in November for working with a foreign organisation.

While Novak was originally supportive of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and was initially critical of the “no to war” hashtag that became popular following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, her stance shifted during the first months of the war.

We can be fairly sure that Novak ended up in prison due to her last place of work: Sibir.Realii. Novak’s colleagues and relatives don’t deny that she worked there. As we cannot see a Novak byline on the Sibir.Realii website, we can assume she was writing under a pseudonym, as many Russian journalists who work with overseas media organisations are forced to today.

Novak’s mother told Sibir.Realii that she understood from her daughter’s case files that she was arrested precisely because of who she worked for. Her relatives say she had a chance to leave Russia, like many of her Russian colleagues who worked for the Russian-language services of RFE/RL, but chose not to.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]