Earlier this month, Russia’s state broadcaster showed an interview with Ksenia Karelina, a 32-year-old woman from Yekaterinburg in the Urals who had been sentenced to 12 years in prison for treason. Karelina, a citizen of both Russia and the US, travelled to Russia in February to visit her relatives, only to find herself arrested for transferring $50 to the American charity Razom for Ukraine, for which she was convicted in August.

As the camera panned across her cell, showing its bunk beds and barred window, Karelina insisted she hadn’t thought her money would be used for military purposes, but admitted that she hadn’t looked into the charity to which she was donating in any detail, adding that she had simply wanted to provide people who had lost their homes with warm blankets.

It’s notable, however, that the interview, the setting, the mea culpa from Karelina, who had probably been given a choice between getting her name on the list for the next prisoner exchange with the West if she confessed on TV and serving her entire sentence, has been copied in its entirety from the Belarusian playbook.

Ksenia Karelina interview. Screenshot: VK

The Belarusian regime has perfected two video confession formats. The first is an instant pile-on by security forces straight after the arrest, where they take the prisoner to an official setting and record a short video. The arrestee says what they do for a living, what they were doing in August 2020, when protests broke out in light of another rigged presidential election, and why they have been detained. If the detainee is a high-earner, such as an IT specialist, they are also made to declare their salary, and a comment will be added to the video saying had they chosen to live a quiet life, they would not now be working unpaid for the state for the next five years.

The videos are then posted on Belarusian Telegram propaganda channels, as well as those run by the security forces, though Telegram sometimes deletes individual videos as well as entire channels. A video of a beaten up Dzianis Dzikun, who was convicted of treason and terrorism for an act of arson against Belarus’s railway infrastructure in 2022, disappeared along with the channel that published it. But Belarusian human rights group Viasna took a screenshot of the video so that nobody should be in any doubt that Dzikun was brutally beaten up while in custody.

Dzianis Dzikun. Photo: Viasna

In another typical example: a hairdresser and mother of several children from the Belarusian city of Orsha is detained mid-haircut at work and taken to the Interior Ministry’s Directorate for Combating Organised Crime and Corruption, commonly known as the Belarusian Gestapo. The woman then confesses to leaving over 600 social media comments critical of the security forces and dictator Alexander Lukashenko since 2020, and then, in keeping with the format, expresses her contrition, explaining that she hadn’t been thinking about what might happen to her children when she made the comments.

Orsha woman who wrote more than 600 comments critical of Lukashenko. Screenshot from re6ion Telegram channel

The Belarusian authorities have pioneered group confessions too, when several people are detained in the same case or, rather, are targeted in a single campaign of repression. A year ago, Polish language teachers and course organisers started being detained when the state decided to launch a crackdown on the practice. The Belarusian authorities decided at the time that the Polish ID card Belarusians of Polish origin were entitled to was a threat to national security. A security forces Telegram channel posted a video where five Polish teachers all said that they taught Belarusians the language to help them pass the exam to obtain a Polish ID card. The text accompanying the video said that these people campaigned for Polish ID cards “to ultimately send enslaved Belarusians to Poland”.

But, of course, a full-length interview that includes a long and detailed confession to be broadcast on state TV is always far preferable to a minute-long video filmed on the fly moments after somebody has been arrested or beaten up.

Belarusian political prisoner Darya Losik, who was sentenced to two years in prison on “extremism” charges in October 2022 for an interview she gave to the Polish-funded TV channel Belsat, was given an entire spot on state TV, showing her daily life in a penal colony in Homyel, followed by a heart-to-heart with a TV propagandist over a cup of tea.

The interview itself focused on Darya’s husband, blogger Ihar Losik, who is serving a 15-year prison sentence on politically motivated charges of “organising mass riots” and “inciting hatred”. Or, rather, on Losik accusing her husband of involving her in “extremism” without a thought for the fate of their young daughter, and announcing their divorce that followed her complete disillusionment in her husband and the opposition.

Screenshot from the interview with Darya Losik. Photo: NEWS.BY / YouTube

Two months after the interview aired, Losik was pardoned, indicating that the “heart-to-heart” was likely a condition of her release.

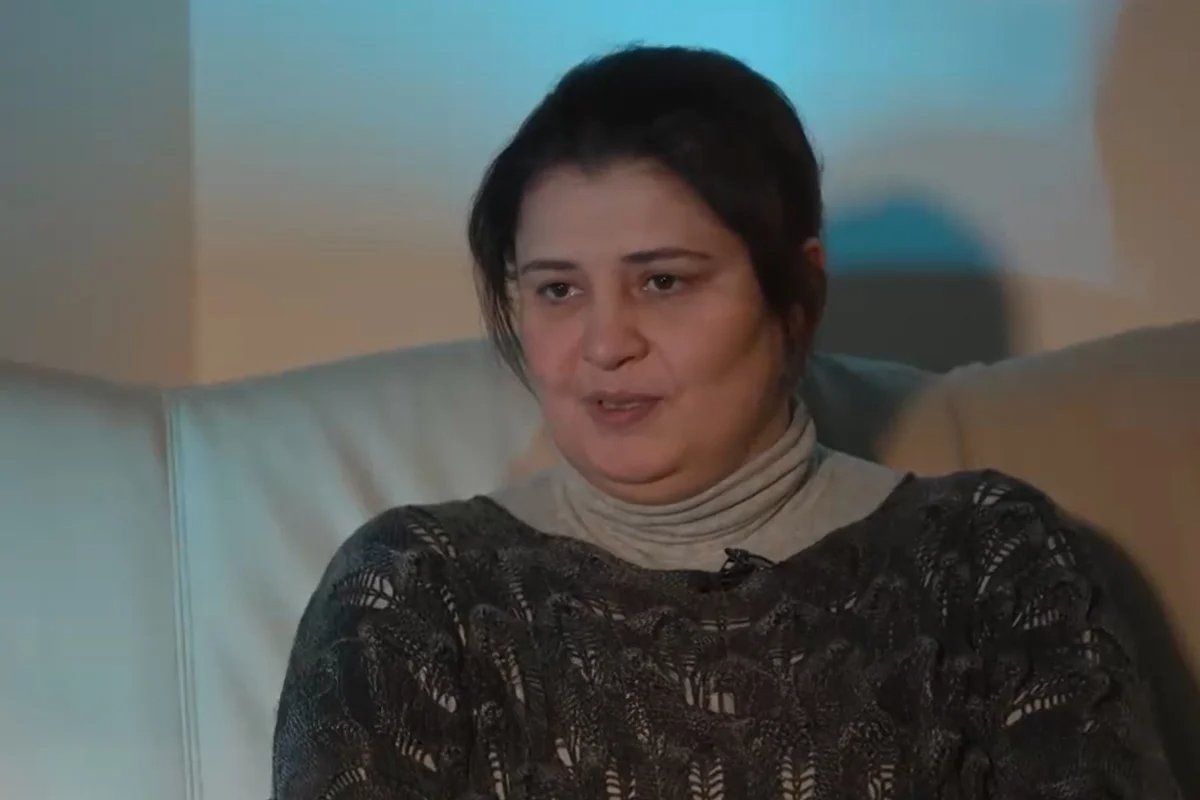

No less obscenely cynical is the prison confession interview with Tatsiana Kurylina, administrator of the 97% opposition Telegram chat network, which aired in February 2023. Kurylina wasn’t filmed against a prison backdrop, but rather seated on a white leather sofa. Propagandist Ksenia Lebedeva looks on sympathetically while seated opposite on a white leather chair.

Kurylina looks exhausted, depleted. She speaks slowly, with difficulty, as if trying to remember her lines. She says that people are fed up, there is no going back to protests, everyone is tired and wants a normal life. At the end of the interview, Lebedeva says that Kurylina is an example to all those who have left the country — she, like many other Belarusians, returned to Belarus from abroad because “things are better at home”. A few days later, it emerged that Kurylina had been lured home under false pretences by the security forces and was jailed for four and a half years in a women’s prison in Homyel.

Tatsiana Kurylina. Photo: NEWS.BY

Perhaps those who claim that the Russian authorities are closely watching what is happening in Belarus and are only too happy to adopt the most cynical and vile methods to combat dissent are right. Or maybe those who say that Belarus is a Russian testing ground are right, and Belarus tests the vilest methods before they are tried in Russia itself. Though it doesn’t matter either way. The fact is, the worse the Belarusian regime behaves towards its people, the more likely it is that the same methods will soon be used in Russia.