The Russian Constitution, which laid the foundations for a democratic post-Soviet Russia in which the protection of human rights would be sacrosanct, was widely seen as a fresh start for the country after 70 years of communist rule. Sadly, however, it has been reduced to just another tool for Vladimir Putin to extend his rule while violating the key rights and freedoms it enshrines.

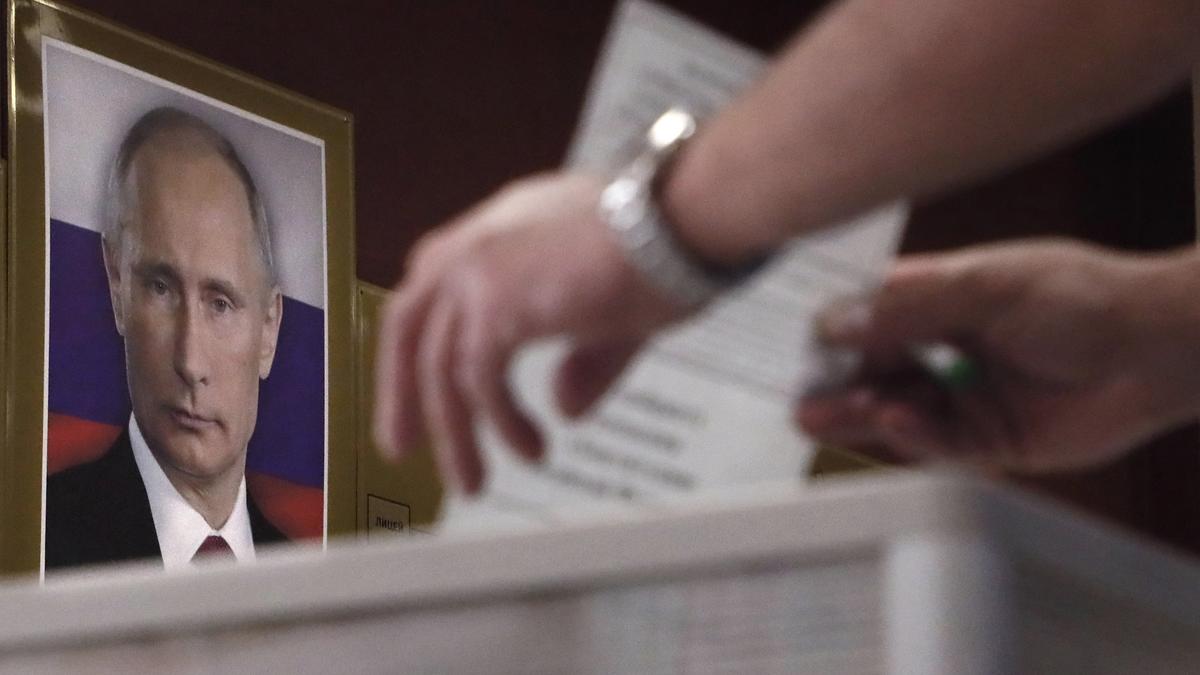

It was in the summer of 2020 that the Kremlin held a week-long “referendum” in the midst of the raging coronavirus pandemic to demonstrate popular consent to its newly rewritten version of the constitution, for which nearly a third of the original document’s 137 articles were revised.

The referendum, which due to social distancing concerns, saw citizens voting at makeshift polling stations set up in places as disparate as tree stumps and in car boots, made a further mockery of the electoral process established by the very document the government was now so eager to change.

The revised Russian Constitution enshrined so-called “traditional values”, including redefining marriage as “a union between a man and a woman”, effectively making the legalisation of same-sex marriage at some point down the road impossible, as well as several other populist measures such as linking pensions to inflation and mandating that the minimum wage must always remain above the poverty line.

Most importantly of all, of course, the 2020 constitutional amendments “reset the clock” on Putin’s already two-decade-long rule, allowing him to seek two more terms as president, potentially keeping him in the Kremlin until 2036 and avoiding a repeat of the humiliating constitutional fudge of 2008, which saw Putin and his then-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev swap jobs for four years.

The fanatically stage-managed and fraudulent referendum resulted in the Kremlin’s amendments receiving the approval of over 78% of voters.

Most importantly of all, of course, the 2020 constitutional amendments allowed Putin to seek two more terms as president, potentially keeping him in the Kremlin until 2036.

“Strange as it may seem, most experts agree that the Russian Constitution is top-notch in terms of its system,” legal scholar and professor at Moscow’s Free University Yelena Lukyanova told Novaya Gazeta Europe, noting however that should Putin’s regime finally fall, several articles would require amendment to ensure another usurpation of power didn’t occur, to strengthen local government and to guarantee free and fair elections.

“It is also important to strengthen human rights guarantees and create strict prohibitions on warfare,” Lukyanova added. “To achieve this, the judicial system must cease to be an instrument of violence and must instead become a method of dispute resolution.”

All of this is already in the constitution, Lukyanova pointed out — but its provisions needed to be supplemented with checks and balances that prevent the abuse of power.

Opposition activists line up to lodge protests against the result of a referendum to amendment the Russian Constitution, 4 July 2020. Photo: EPA-EFE/MAXIM SHIPENKOV

“Unfortunately, in 2020, Vladimir Putin made the constitution radically worse. Although the first two chapters — on the foundations of the constitutional order and human rights — remained unchanged, other chapters were deliberately changed in such a way to make it as difficult as possible to implement the first two. We call this a constitutional coup,” Lukyanova continued.

The Constitutional Court — an institution empowered to rule on whether certain laws or decrees breach the constitution, did nothing to stop this coup, Lukyanova said. “Of course, in the future, all the amendments that were approved in 2020 will need to be overturned”.

If power in Russia changes hands, Lukyanova said she believed it more likely that any future democratic government would favour abandoning Russia’s current presidential system, for a parliamentary one, which could in fact be done quite easily by slightly amending the current constitution.

Police officers break up an unauthorised protest against the results of a referendum on amending the Russian Constitution in Moscow’s Pushkin Square, 15 July 2020. Photo: EPA-EFE / YURI KOCHETKOV

The original constitution could continue to be used as a transitional document until the new government bodies could be formed and the judicial system could be changed, she explained, all of which would be likely to take a while.

“But not everything written on paper can come into being at the drop of a hat,” Lukyanova warned. “We will need time to create a ‘constitutional culture’ and to accustom society to the fact that the constitution is a document that cannot be questioned.” This, in turn, would require functioning courts and the strict enforcement of the law, which would be in the best interests of both the state and its citizens.

“Constitutions generally don’t tend to exist due to having state support, but because their provisions are defended by the population,” Lukyanova explained.

“We will need time to create a ‘constitutional culture’ and to accustom society to the fact that the constitution is a document that cannot be questioned.”

While there was no such practice in the Soviet Union, in recent decades, Russian society has somewhat accustomed itself to the need to protect its rights, as evidenced by the growing number of legal battles in the country — from disputes over property to ones over copyright, Lukyanova argued.

However, as human rights NGO First Departments pointed out, dozens of Russian laws, including its infamous wartime censorship, the “foreign agent” law and legislation promoting “traditional values”, violate the essential freedoms enshrined in both versions of the constitution.

And despite Moscow’s pompous assurances that the current version of the constitution “preserves” Russia’s integrity and guarantees the country’s development, its main — if not only — function for the next decade or so is to ensure he can remain in power for as long as humanly possible.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]