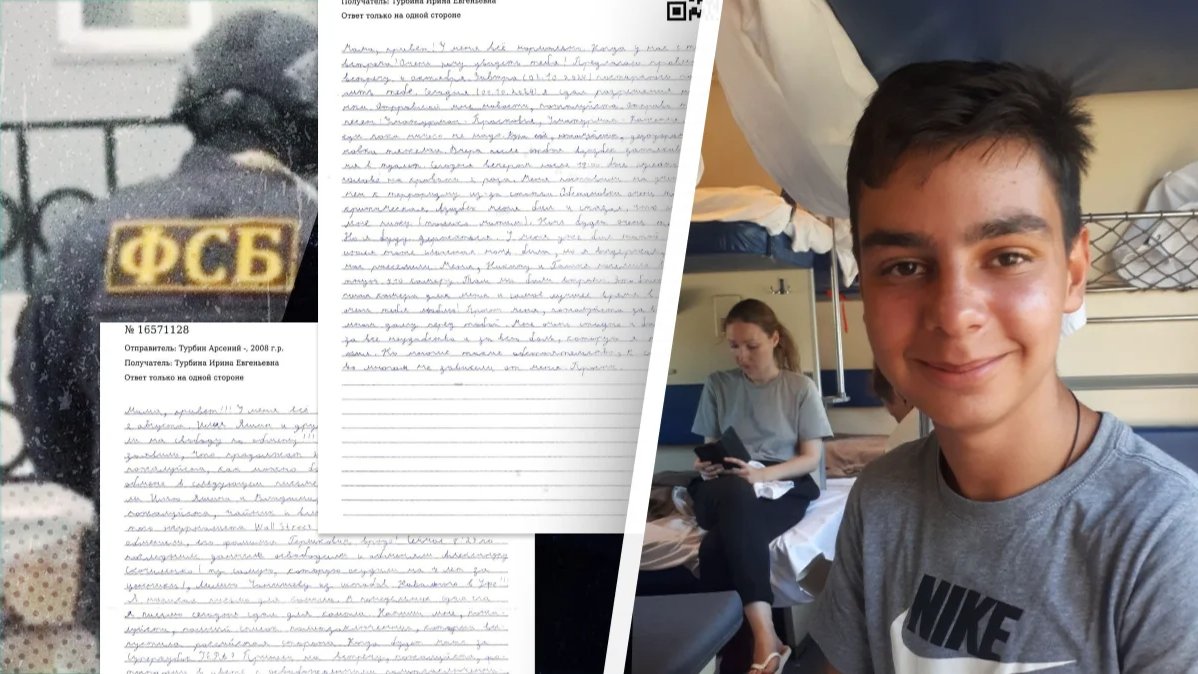

“The situation is very difficult, critical,” wrote Arseny Turbin, one of Russia’s youngest political prisoners, to his mother in October after his cellmate punched him while he was in bed and then proceeded to force his head into the toilet bowl. “The night will be very hard. But I will hold on,” the teenager, who was found guilty of “terror offences” aged just 15, added.

Turbin, from a small town of Livny in Russia’s western Oryol region, was sentenced to five years in prison in June. The case against him was opened by the authorities over posts he made that were critical of Vladimir Putin on his Telegram channel, Free Russia, even though it only had five subscribers.

At one point, Turbin and his mother Irina even dared hope that the charges against him could be dropped, as he was not remanded in custody while the investigation was ongoing. However, immediately after being found guilty he was placed in a Moscow juvenile detention centre. His appeal is scheduled to take place on 30 October.

“There were problems in the cell as soon as Arseny got to the detention centre,” Irina says. “The staff, including the psychologist, saw Arseny as a complicated case, because he didn’t keep his mouth shut when more compliant children would.”

“Why should I agree with them? They try to provoke conflict, and I have to apologise to them? I won’t.”

According to her, Arseny counters: “Why should I agree with them? They try to provoke conflict, and I have to apologise to them? I won’t.”

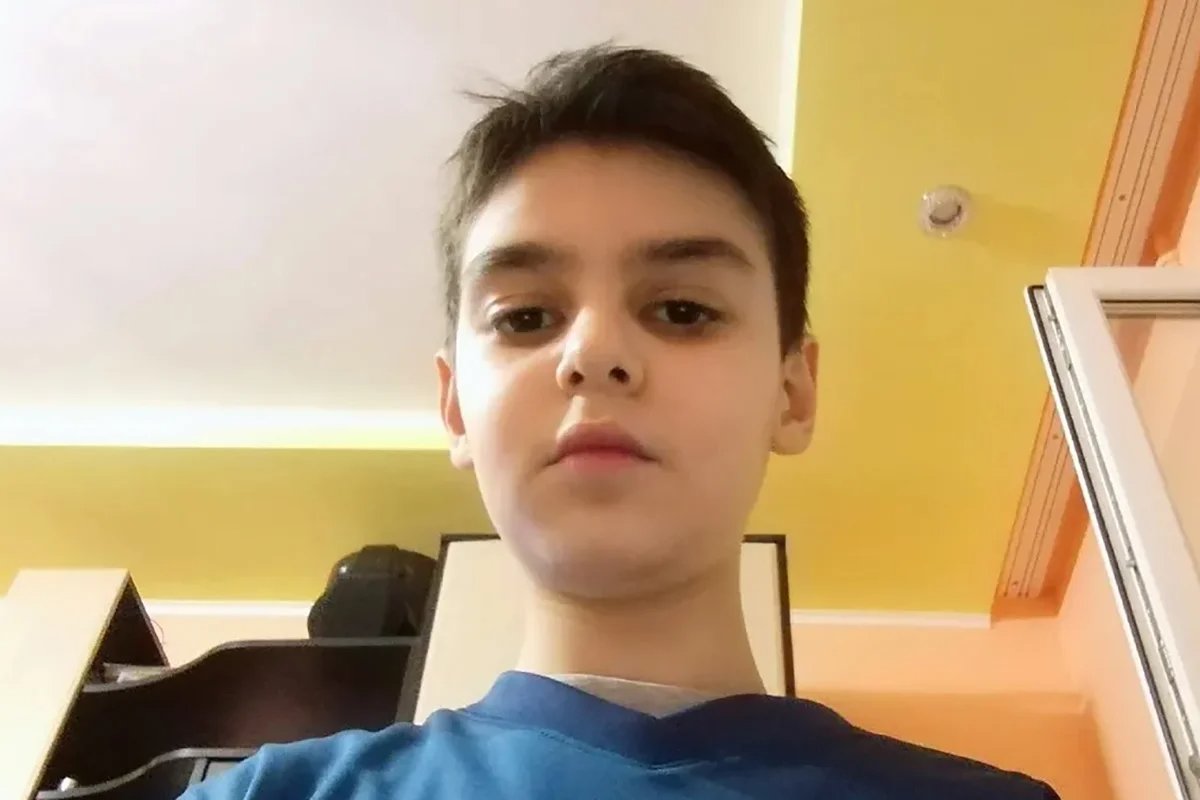

Turbin was normally in good spirits during her visits, Irina says, recalling that he asked to be kept updated about the news, and asked his mother to print out maths exercises for him. But as time went by, his life in prison became more difficult — Arseny told his mother that July was one of the hardest months, as his cellmates would rip up his maths exercises and wouldn’t let him watch the news on TV.

Arseny Turbin with his mother Irina. Photo from the family archive

In August, after news of the largest ever prisoner exchange between Russia and the West emerged, Arseny wrote enthusiastically about Ilya Yashin and Vladimir Kara-Murza’s release, asking for more details, and wondering whether it was true that Wall Street Journal journalist Evan Gershkovich was also free.

The new school year began in the autumn, just as it did for children across the country. At the detention centre, they get up at six, but don’t have any lessons until after lunch. Arseny was in the 10th grade when he went to jail and hopes that the one and a half hours a day of lessons he receives there will somehow be enough for him to keep up with the curriculum. Teachers come to the detention centre after their regular jobs.

“He said, ‘Mum, get me out of here whichever way you can. I’m having a terrible time here. What’s the latest with the appeal? I didn’t commit any crime.’”

“They’re meant to be doing 10th grade coursework, but what can you get through in an hour and a half a day?” Irina says. “I hope my son can catch up. He’s a smart boy.”

But when Irina went to see her son on 11 September, she barely recognised him.

“We didn’t tell anyone at the time,” she says, shaking her head. “He had tears in his eyes the whole time. He’d given up hope. … He said, ‘Mum, get me out of here whichever way you can. I’m having a terrible time here. What’s the latest with the appeal? I didn’t commit any crime.’”

Arseny had a huge cut on the back of his neck. He said he had a new cellmate, a big guy called Azizbek. The day before, Azizbek had thrown a piece of tile at Arseny when he was showering that struck him in the back of the neck. When he blurted out that an extended stay in the detention centre could be the death of him, Irina could only exclaim in horror, “What on earth are you saying?!”

“I left there in tears,” she continues. “It’s like my body turned to stone. I had such a lump in my throat I couldn’t swallow. He wasn’t even like this on the day of the verdict. That day he was very upset, but not as depressed.”

Arseny told nobody but his mother about the abuse. “He saw what happened to people who complained,” Irina says, her eyes closed. “One guy complained, word got out, and he got beaten up and raped with a toilet brush. The nice teacher and the psychologist both tried to speak to Arseny. They told him that he was too direct.”

Arseny Turbin. Photo from the family archive

The next day Irina went to see the detention centre’s deputy head of education and demanded he stop her son being bullied. She was assured everything was being done to make sure Arseny had the best cellmates possible. Irina didn’t believe him, but on her next visit Arseny told her that Azizbek had been moved.

In October, it emerged that Arseny had lost 17kg in four months in detention, during which time he barely ate.

But it has all taken its toll. In October, it emerged that Arseny had lost 17kg in four months in detention, during which time he barely ate. In a recent letter, he asked his mother to order him more food, which Irina took as a sign that he was feeling better.

Arseny’s appeal will be heard on 30 October. Irina tries not to think about how her son will cope with his transfer if the verdict is upheld. The most serious charge against Turbin is that he joined, and was active in, the Freedom of Russia Legion, a battalion that fights alongside the Armed Forces of Ukraine against the Russian military. That, combined with the flyers criticising Vladimir Putin he posted in local people’s mailboxes, his Telegram channel being called Free Russia and the photos of him carrying the white-blue-white flag of the Russian anti-war movement, will all be used as evidence against him.

The Federal Security Service’s (FSB) transcript of Turbin’s interrogation alleged that he had filled out and emailed an application form to join the legion, which has been classified as a terrorist organisation in Russia. An audio recording of the interrogation played back in court revealed that he had in fact said the exact opposite of what was on the FSB’s version of the transcript. Turbin has always maintained that never sent off the Freedom of Russia Legion application form.

Still, the judge ruled that the discrepancy between the audio recording and the transcript was a mere “technical error” and proceeded to dispassionately hand down a five-year prison sentence to a minor, while nobody initiated criminal proceedings against the investigators for evidence tampering.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]