When Alexey Bachinsky completed his journalism degree in 2011, he was already well aware that he could never work for Russian state television. Thankfully, at that time independent media still existed in the country, and so he found a position at independent news outlet Grani, before moving to socio-political comment and analysis site Kasparov.ru.

A year before graduating, Alexey had met a Belarusian graphic designer named Andrey*, and the pair had fallen in love. When they met, Andrey lived in the Belarusian capital Minsk, where he had been involved in anti-Lukashenko protests since the 2006 presidential election.

Andrey moved to Moscow in 2011 to live with Alexey, where, among other things, the two attended pro-democracy rallies and marches together. Almost a decade later, however, Andrey made a special journey home to cast his vote against Lukashenko in the 2020 presidential elections and then joined the hundreds of thousands of other Belarusians in the street protests that followed the obviously falsified results.

Long before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Alexey and Andrey anticipated that the adverse political climate in Russia would one day force them to move abroad, and so in 2014 they travelled preemptively to Denmark to get married.

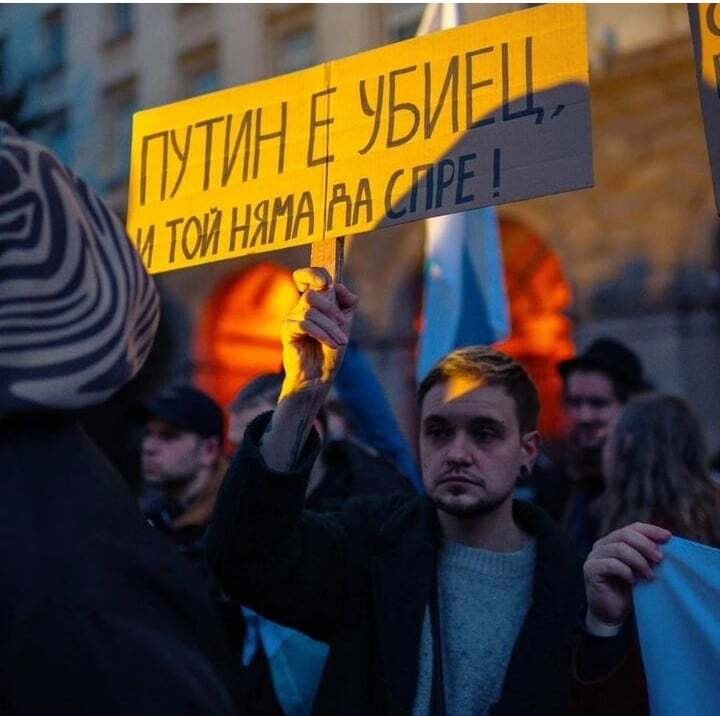

Alexey at an anti-Putin rally in Sofia, Bulgaria. Photo from personal archive

While their Danish marriage certificate carried no legal weight in Russia, Andrey and Alexey hoped that in the event they had to flee Russia, their marriage would at least be taken seriously by the authorities in more progressive countries. They were wrong.

“When the invasion began, we didn’t decide to leave immediately,” says Alexey. “At first I thought that we should carry on working in Russia, write about what is happening, and try to do something about it. But then journalists at Kasparov.ru started receiving threats. They threatened everyone.”

The calls came from different numbers, Alexey said, but to his knowledge, they had links to the Centre for Combating Extremism, an anti-extremism unit within the Russian Interior Ministry that is known for persecuting opposition activists. “At some point I realised it was too dangerous to stay in Russia, and so I went to Bulgaria in September 2022, and Andrey followed me in December,” he continued.

Bulgaria wouldn’t have been their first choice, but it was one of the only countries in the European Union still issuing visas to Russians and Belarusians at the time. They considered applying for Spanish visas, but it would have taken much longer at a time when they knew any delay could have serious consequences. They were both afraid of being trapped if Russia closed its borders or if there were crackdowns on the LGBT community, opposition activists or journalists.

“At some point I realised it was too dangerous to stay in Russia, and so I went to Bulgaria in September 2022, and Andrey followed me in December.”

They decided to leave Moscow on the same day. When Alexey called to say that he had gone through passport control and was boarding his flight to Istanbul, Andrey got into the car and drove to Belarus to apply for a Bulgarian visa. They decided driving was the safest option as there are only occasional checks on the Russian-Belarusian border, and Andrey was waved through without a problem. Once his Bulgarian visa had been issued, he drove back to Moscow, from where he flew to Bulgaria.

By the time Andrey arrived, Alexey had already applied for political asylum in Bulgaria. The process took a year and a half, but in April Alexey was granted refugee status, given international protection, an international foreigner’s travel document and an internal refugee ID card. Andrey submitted his asylum application upon his arrival in Bulgaria, but was informed after an 11-month wait that the authorities had turned him down.

“Bulgaria doesn’t recognise same-sex marriage,” Andrey explains. “Our marriage certificate means as little in Bulgaria as it does in Belarus and Russia. … My rejection said that Alexey and I were just friends, which meant I wasn’t affected by the risks he faced. … We are nobody to each other.”

“The State Agency for Refugees told me everything would be fine if Andrey went back to Russia. So they recognised that I face a risk, but not that my husband did,” Alexey adds.

People attend a Pride Parade in downtown Sofia, Bulgaria, June 2022. Photo: EPA-EFE/VASSIL DONEV

In a recent case, the immigration authorities in Montenegro rejected a request for asylum from a Belarusian opposition activist on the grounds that Belarus had signed a number of international treaties that meant it complied with international standards.

Nothing surprises Alexey these days, he says. When the first Russian applicants for international protection in Bulgaria were turned down in 2022, those decisions were often accompanied by grandiose statements made by Putin and other senior Russian politicians about Russia being a democracy that respects the rule of law. That, at least, doesn’t happen now and it has become easier for Russian activists to be granted asylum.

That said, Belarus remains a largely unknown quantity in Bulgaria, despite the fact that as an EU member, the country’s government has supported the wide-ranging sanctions currently in place against the Lukashenko regime. Lawyers have told Alexey and Andrey that one of the main arguments used by the Bulgarian authorities when rejecting asylum applications from Belarusians is that as Belarus is not currently engaged in any military conflicts, it must therefore be safe to live there.

“Our marriage certificate means as little in Bulgaria as it does in Belarus and Russia.”

Andrey has now unsuccessfully appealed the agency’s decision twice, including at the Bulgarian Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ruled that belonging to a certain social group was not a basis for being granted refugee status. The court also ruled that as Alexey’s marriage to Andrey was not legally recognised in either Russia or Belarus, Andrey ran no risk of being persecuted for being gay should he return to either.

The Supreme Court ruling also noted that discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation was commonplace even in well-developed democracies. Indeed, Bulgaria is moving even further to the right in terms of such discrimination, with the Bulgarian parliament fast-tracking a new law banning “LGBT propaganda” in schools on 7 August, following the introduction of a bill by the pro-Russian Vazrazhdane (Revival) Party. The new law, essentially a copy of comparable Russian legislation, bans the dissemination of information about “non-traditional sexual orientations” and gender identity.

“I tried to explain what was happening in Belarus,” says Andrey. “I printed information from human rights activists about the scale of repression and UN reports and EU resolutions — anything to give Bulgarian officials a true picture of what was happening in my country. But it was completely useless. … Belarus has brought in amendments to the law this year, criminalising the open demonstration of same-sex relations and equating that to pornography.”

It is perhaps no surprise that the State Agency for Refugees should know so little about the situation in Belarus. According to agency statistics, just one citizen of Belarus applied for asylum in Bulgaria in 2021. By comparison, some 6,000 Afghans and almost 4,000 Syrians applied for asylum in the same year, so resources are inevitably focused on asylum seekers from elsewhere with very different safety fears.

The Supreme Court made its decision on 17 September, though Bulgarian law requires the court to transmit its ruling directly to the Migration Service before it can be enforced. Nevertheless, at some point soon Andrey will be given written instructions to leave the country within either 14 or 30 days or face deportation.

Activists hold the white-blue-white flag, considered a symbol of the Russian anti-war movement, and the white-red-white flag, symbolising a free Belarus, at a rally in Sofia. Photo from personal archive

But Andrey is already adamant that he won’t leave Bulgaria without a fight, and that he and his husband will continue to defend their right to be a family even in a country that doesn’t recognise them as such.

Among the legal strategies he and his lawyers plan to employ are making a fresh asylum application to the State Agency for Refugees on the grounds that Belarus has recently amended the legal situation for its LGBT community. They also plan to take Bulgaria to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) for violating their human right to family reunification.

“The ECHR ruled on another case,” says Alexey. “Saying that even countries that don’t recognise same-sex marriage should consider such unions valid when considering whether to grant somebody refugee status. So it should be quite simple from a legal point of view.”

The only question is how quickly Rule 39, an interim measure that the ECHR can use to halt the expulsion of an individual by a member state while it reviews their case, will come into effect, and more importantly still, whether it or a deportation order by the Bulgarian authorities, will be issued first.

* Not his real name