Since 2022, Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has quashed the rehabilitation of at least 4,000 people who were found guilty of treason and collaboration by the Soviet government during World War II.

During that time its experts have reviewed some 14,000 cases in which convicted individuals were posthumously rehabilitated in the 1990s and 2000s. Details of the revised decisions have not officially been disclosed, but the Prosecutor General’s Office has responded to some individual requests for information.

Why are the Russian authorities so keen to row back on some landmark exculpatory decisions that once defined an era of democratic transparency?

Realigning policy

Memorial estimates that almost 7 million people were subjected to repression at the hands of the Soviet regime between 1918 and 1987, of whom around 5 million were prosecuted for political crimes. Over 1 million people were executed, usually shot in the head, with the rest sent to the gulag or to penal colonies, and a lucky few forced into exile.

At least 6 million others were subject to mass deportations. In total, between 11 million and 11.5 million people were repressed for political reasons in the USSR. Of those, 3.5 million people were rehabilitated between 1991 and 2014.

A man lays flowers at the Wall of Grief in Moscow, 30 October 2022. Photo: Yury Kochetkov / EPA-EFE

Despite it being Russian state policy to memorialise the victims of Soviet political repression in perpetuity since 2015, in early September it emerged that the Russian authorities had significantly rewritten their policy on how the victims of Soviet repression should be remembered. Among other things, the official narrative now denies the “mass” nature of Soviet terror and doesn’t name those responsible for carrying it out.

In particular, a passage stating that “Russia cannot fully become a state based on the rule of law and take a leading role in the global community without commemorating the many millions of its citizens who were victims of political repression” was removed from the document’s preamble.

Memorial historian Alexander Cherkasov says the authorities intend to analyse the rehabilitation of victims of political repression over the next two years and then to complete their work on how the victims of political repression should be remembered in the next few years.

The Russian authorities did not limit itself to rewriting a single policy, however. In September, it emerged that the Prosecutor General’s Office had rescinded the rehabilitation of over 4,000 victims of Soviet political repression over the past two years. In doing so, it stressed that Soviet citizens who voluntarily joined “paramilitary formations of the Wehrmacht and SS” or who had otherwise collaborated with Nazi administrators in occupied areas of the Soviet Union had been erroneously rehabilitated.

The Prosecutor General’s Office claims to have come across more servicemen employed by the Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany, and “other Soviet citizens who assisted the German Nazi authorities during the occupation” in the course of their inspections.

Visitors at Moscow’s Gulag History Museum, 30 October 2015. Photo: Maxim Shipenkov / EPA-EFE

‘A crime against history’

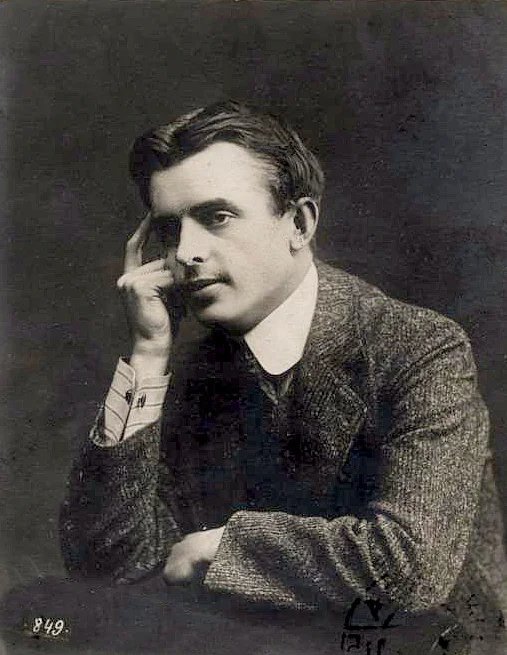

Vsevolod Blumenthal-Tamarin, circa 1910. Photo: Archishenok /Wikimedia

In February 2024, the Prosecutor General’s Office overturned the rehabilitation of Russian actor Vsevolod Blumenthal-Tamarin who began to collaborate with the German forces in 1941, broadcasting radio appeals for Soviet citizens to surrender.

Blumenthal-Tamarin, who fled to Germany where he was killed in murky circumstances in May 1945, had been sentenced to death in absentia by the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union. In 1993, he was rehabilitated, but this year the Prosecutor General’s Office found his original conviction to be justified and legitimate, saying that Blumenthal-Tamarin had “defected to the enemy, began to cooperate with the German occupiers, and called for people to fight against the Soviet state on the radio”.

Another relatively high-profile case was the revocation of the rehabilitation of Joseph Chernov, the former Metropolitan of Kazakhstan, which was announced in August. Prior to World War II, Chernov had twice served prison sentences for “inventing and spreading counter-revolutionary rumours” and for anti-Soviet agitation.

Metropolitan Joseph Chernov of Kazakhstan. Photo: Petropavlovskaya and Bulaevskaya Diocese

Under German occupation, Chernov was again permitted to conduct church services, which the Bolsheviks had forbidden. Chernov’s 1992 rehabilitation was found to be invalid by the Prosecutor General’s Office due to his “complicity with the invaders”.

Exactly who else features among the other 4,000 rehabilitations that have been overturned is anyone’s guess, as once a final decision on a case has been made, its documentation becomes classified.

“Now, for example, researchers do not have access to the files on the secret police, which certainly contain details of the atrocities they committed,” says Mikhail Sheinker, a researcher at public memorial project Last Address, which commemorates those who died at the hands of the Soviet authorities. “This is a crime against history.”

Visitors attend an exhibition on the crimes of Stalinism, Moscow, November 1988. Photo: Dmitry Borko / Wikimedia

Crime and punishment

Yan Rachinsky, a former chairman of Memorial, believes that in revising its approach to the past, the Prosecutor General’s Office is attempting to promote a statist ideology of Russia as a great power, in which the state is viewed as sacrosanct, and anyone who defies it as a traitor.

While the historians agree that there will be no mass reversal of post-Soviet rehabilitations, the work will nevertheless require huge manpower and will therefore take a significant length of time.

“At first, they didn’t want to rehabilitate anyone who’d worked in Nazi-occupied territories. That’s a problem in any war. What should people who live in occupied territory do?”

Boris Belenkin, a Memorial board member, has suggested that although the Prosecutor General’s Office is “unable” to reconsider all decisions, even a few cases might be enough to sow “confusion in the minds of Russians”, leading people to think things aren’t clear-cut when it comes to cases of people falsely accused of treason. “This will likely change social attitudes towards rehabilitated victims of repression,” he added.

The Prosecutor General’s Office now enjoys a broader remit than it did in the 1990s, according to Rachinsky, who describes the recent changes as a return to the Stalinist approach, when prisoners accused of treason were considered to be guilty until proven innocent.

“At first, they didn’t want to rehabilitate anyone who’d worked in Nazi-occupied territories. That’s a problem in any war. What should people who live in occupied territory do?”

Yan Rachinsky. Photo: Gleb Shchelkunov / Kommersant / Sipa USA / Vida Press

Once Soviet territories were recaptured from Nazi occupation, the secret police didn’t trouble themselves overly with the details of who was complicit or who collaborated, Rachinsky continues, and as a result many village elders from formerly occupied territories were sent to camps, where some were shot.

Rachinsky stresses that another key aspect in reversing rehabilitations is how such decisions will affect the descendents of those concerned. “If a person was convicted, then was considered to have been convicted without evidence, and it’s now been decided that they were in fact guilty after all on some grounds or other, those grounds need to be very convincing.”