While villagers who live nearby believe the three-storey building in rural Tatarstan where a Novaya Europe correspondent recently spent a week working as a nurse to be an abandoned prison, it is, in fact, a tuberculosis (TB) clinic, one of 143 such facilities in Russia. Here, in cold wards where tepid brown water is served up as tea and the taste of rotten meat is poorly disguised by adding pepper, lonely people die every week of a disease that is perfectly curable.

No entry

The three-storey building in the middle of the forest has no sign to indicate what it is or does. The fence around it was once grey but is now covered in mould and has turned green. There is no gate, and anyone wishing to enter the facility is forced to bend down and slip through a makeshift hole in the fence.

The smell of boiled cabbage, sweat and other human exudations hits you immediately on the way in. This is not an abandoned building nor a venue for murder mystery parties, this is a regional Russian tuberculosis hospital.

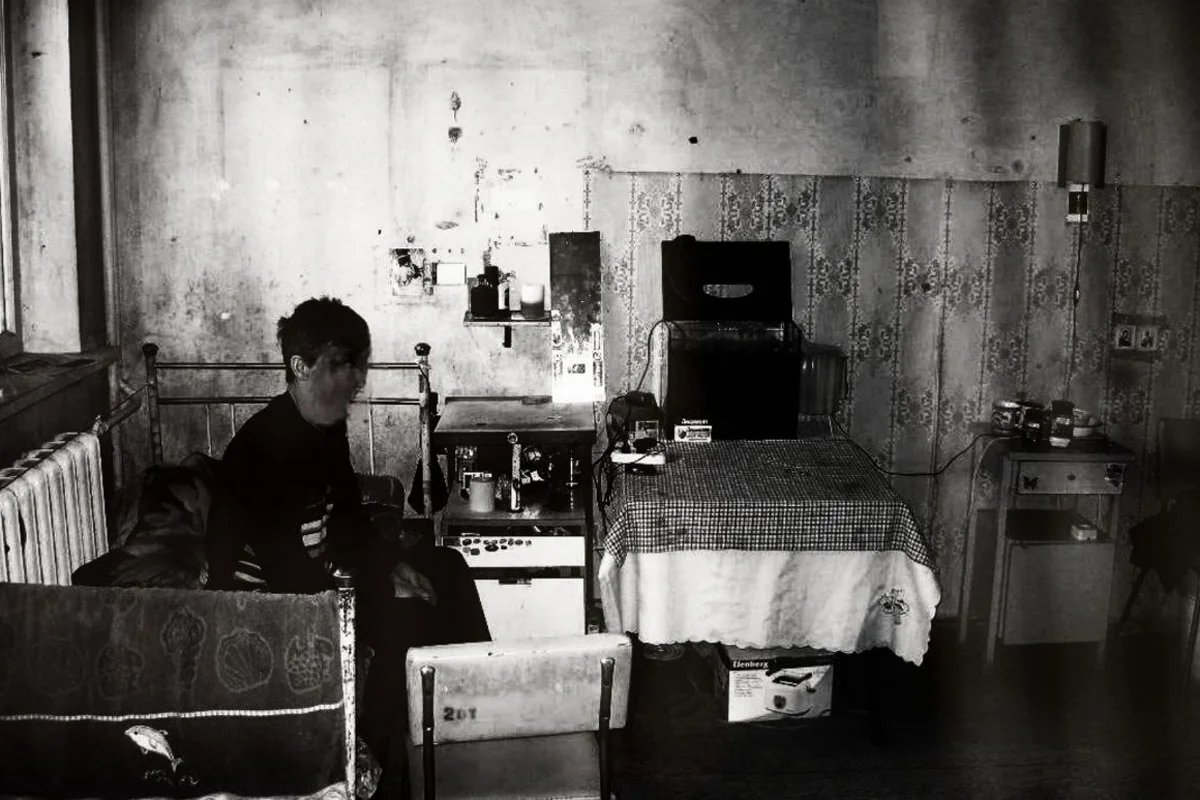

The battered concrete ceiling must have been white at some point before the millennium but has turned grey with age and each of its corners is thick with spider webs. Below it, the concrete floor, covered with linoleum, is as cold as the grave. In some places, the lino is torn, and clumps of dirt can be seen throughout the wards. Both patients and staff walk around the hospital in their outdoor shoes, something so culturally alien to Russians that it can only suggest defeat.

Each floor has 30 rooms, most of which are for patients. There are handles on the doors of the ward for patients with latent TB on the ground floor, but no doors at all on either the first or second floors, where there is a ward for patients with active TB and a palliative ward for those who are dying.

While doctors rarely go to the first or second floors, nurses go up a couple of times a day. Patients, however, go upstairs only once, and come back down in black body bags.

Two elderly ladies work as medical assistants whose tasks include distributing medication to the patients and mopping the floors in the palliative ward. Despite earning just 15,000 rubles (€145) a month, they ask each patient about their physical and mental health on their daily rounds and bring the patients food they cook at home almost every day.

If asked for wine or cigarettes, they buy those too, calling the patients either “kyzym” — Tatar for daughter — or “ulym” — Tatar for son. If a patient dies while they’re on duty, they’ll also recite a prayer for their soul before their body is put into a body bag.

The only treatment available in the facility is pills. The food cannot be called high-calorie, which is the diet required by TB patients. There is no milk in the porridge, no effort is made to make the soup smell nice, and instead of hot drinks, the patients must make do with warm water.

The clinic’s monthly meat delivery. Photo: Asiya Nesoevaya

A slaughtered cow is brought to the hospital once a month. The nurses and their assistants butcher the meat, shooing flies as they go. Beef is then served with every dish as it will go off due to the poor refrigeration at the clinic if it isn’t eaten within three weeks. If it does go off, they add more black pepper and serve it up anyway, I was told in confidence.

And if that happens, the toilets, or, rather, the holes in the ground, won’t be cleaned until the end of the week. The doctors do their rounds on Sunday, and if they see soiling, they order the patients to clean the floors themselves, but just the floors. Nobody will tell them to dust or wash the bed linen because there is no bed linen or any furniture for dust to gather on. People sleep on bare mattresses stained brown with dried blood. There are always bloody tissues by the sinks too. Patients spit straight into the sink and often leave globules of blood behind.

The saying “the walls have ears” takes on a new meaning in a place so poorly built: you can hear the patients upstairs with active TB snorting and spitting blood from the ward below.

One nurse tells me that both drunkenness and violence are common, and that it’s sometimes necessary to call out the police. Alcoholic patients tend to stick together, while those prone to violence usually fight among themselves.

There is one unisex toilet on each floor, and it’s the closest thing the clinics have to a dating area: there are always people canoodling in these areas. I came across one couple who said that they planned to marry if they survived the clinic, though they each first needed to divorce their current spouse. Indeed, they refused to speak to me on the record for fear that their families would find out about their affair.

Socioeconomic disease

The TB clinic differs from a conventional hospital in two ways. Firstly, this is a closed hospital and only those in whom TB is either suspected or has been confirmed are allowed to enter the building. Secondly, as TB is a socioeconomic disease, the spread of which is largely limited to drug addicts, alcoholics, those with compromised immune systems and anyone who performs extended physical labour in cold conditions, the hospital caters to some of the most unfortunate people in Russian society.

TB is most often passed on when a person with an active form of the disease releases microbacteria from their respiratory tract. If TB goes diagnosed, as can happen, even with symptoms, it becomes a danger to other people. According to World Health Organisation estimates, a single patient can infect as many as 15–20 other people.

It can also be transmitted via dust particles containing microbacteria, or pass from animals to humans via meat and dairy products. TB most often affects the respiratory system, but can also affect the intestines, kidneys and urinary tract, bones, skin and lymph nodes. Symptoms can sometimes take years to appear.

The clinic’s latent TB ward. Photo: Asiya Nesoevaya

Vanya and Fedya

After spending seven years in prison for manslaughter, Vanya moved between various hospitals and police cells for the past three years. He caught TB six months prior to being admitted to the hospital, not that anybody at the police station noticed. There he met Fedya, or rather, a man who introduced himself as Fedya — he can’t recall his own birth name.

Vanya likely infected Fedya with TB at the police station and, as he says himself, managed to infect “a couple of cops too”. But while the police officers went to the city clinic for treatment, Vanya and Fedya ended up on the same ward in the TB clinic.

As they lie there, they discuss who on the ward will die first. Fedya thinks it will be the “fat woman with diabetes”, because diabetics with tuberculosis don’t live long. Vanya is betting on the young thin guy. He’s 32 years old but weighs just 43 kilos.

It took them a long time to decide on the stakes — neither has money nor the prospect of ever making any — so they settled on the matron with red hair, or, rather, having first dibs on making a play for her.

Those with “connections” spend their time in the clinic’s best-equipped ward. Photo: Asiya Nesoevaya

Fedya and Vanya are the only people with “connections” in the clinic with some notion of special privileges. There were five earlier in the summer but two died and the other one’s adult son came and collected him. If one of them were to die with no new patients with similar “connections” arriving, the sole survivor would be expected to “manage the clinic” alone. The male patients think that would be “hard for everyone”, because anyone with too much power inevitably goes crazy. Fedya adds that the surviving tough guy won’t last long anyway so doubts that he’ll have “much time to go mad”.

Fedya and Vanya’s dull existences are occasionally spiced up a little by the screaming and wailing of patients brought in from intensive care, many of whom die. Not a week goes by without two or three people being taken away in black bags. Vanya says he has gradually got used to it.

“There was this girl here two months ago. I saw her a lot. She was beautiful. I liked her. We were watching TV in the common room one evening and I saw her playing board games with the other patients. She was unlucky. Her liver packed in. The pills they give us are hard on the liver and all the other organs too. The next day they took her away in a body bag,” Vanya recalls.

Irina

TB specialists come to the clinic from the city hospital once a week to see the new patients and prescribe treatment. They also remove the stray cats from the grounds and ask the hospital staff to do the same. There are two nurses on each shift, and every day after lunch they take turns shooing the kittens with a yellowing, splintered broom.

Some new patients, mostly women, try to pick the kittens up, especially the small ones. Irina feeds them. She’s the only person in the clinic who does.

It’s not easy. First you have to pocket the food — usually beef or soup fat — without the staff seeing you. The patients with latent TB take a 20-minute walk after lunch when the main doors are opened to ventilate the premises. Irina isn’t allowed outside as she has active TB.

But she had noticed the cats when she was still allowed to go out. So now she waits for the “latents” to move on, approaches the door, calls to the kittens and throws food into the bushes. She is sure they wait for her.

Irina is known here as the “fat woman with diabetes”. For many of the kittens, she was their only hope of survival. Some are so small and skinny they look like mice.

Irina passed away on 3 September. The nurse told me she was fitting when she died. As someone with no next of kin, Irina wasn’t given a burial. Graves are expensive, and therefore TB patients with no family are cremated.

Taisiya

“You’re probably wondering if I’m scared of death,” Taisiya asks. “I’m not. I’ve been lying here for two months, and haven’t got out of bed for the last month. I’ve had enough time to think about life and understand there was nothing interesting or good about it. I’ve suffered enough.”

Taisiya is 54 and the nurses say she has no more than two weeks left to live. Each nurse is afraid Taisiya will die on their shift. She hasn’t been given a bed-pan for a week so it’s hard to breathe around her. That and the odour of a dead body would be unbearable. Nurses are not paid extra for particularly harrowing tasks.

The hospital building. Photo: Asiya Nesoevaya

The first thing the nurses ask when they come into work at 7.30am is whether Taisiya has died. When they hear that she is still alive, they go for tea and argue over who will put her body in the body bag. The matron with red hair had suggested withholding water and food for her to die faster, but her colleagues objected and gave her porridge, made with water, that smelled of household detergent.

Taisiya ate it with great difficulty, struggling for breath. A blonde nurse, her nose buried in her shoulder to hide the smell, hurriedly inserted one spoonful after another into the dying woman’s mouth. Taisiya refused lunch, barely managing to shake her head. She had already lost the ability to speak.

She finally died on the evening of 4 September — nobody appears to know the exact time — while the nurses were drinking tea.

The acrid smell of blood may have briefly interrupted the smell of urine that pervaded the ward, but I found it very hard not to vomit.

One of the two nurses who discovered that Taisiya had died on their rounds let out a loud “fuck!” The nurses put on several surgical masks and turned the body over. There were open purple sores on her shoulder blades, the back of her neck, her heels and thighs.

The acrid smell of blood may have briefly interrupted the smell of urine that pervaded the ward, but I found it very hard not to vomit. It was the smell of something rotten and metallic, as if gastric fluid had been vomited onto snow.

The nurses said Taisiya had “normal pressure sores”. After the body was removed, the youngest nurse turned the mattress over at the matron’s request. Another dying patient, a man of retirement age named Alexey, is on it now.

The head nurse told me that he had “a couple of days left and can’t smell anything”. She promised that when Alexey died, they’d replace the mattress with a “new” one, by which they meant one that the city clinic no longer wanted.

As Taisiya was taken down to the ground floor in a body bag, the matron said: “Thank God, her suffering is over.” The nurses took off their masks, washed their hands with domestic detergent and sat down to eat the cake that one of the assistants had brought in. She didn’t eat any herself. Instead, she went outside, made the sign of the cross over Taisiya’s body bag and touched her toes for a couple of seconds. The nurses tell me of their disgust at her behaviour, which they liken to a mental disorder and even necrophilia.

Most of the patients have gone to bed by now, though some are still playing cards. The nurses joke about the “stinking corpse of the dead old lady”, finish their coffee and apply some hand cream.

Novaya Europe has not used real names or revealed the location of the clinic on security grounds. The correspondent told both staff and patients that she was a journalist.

Novaya Europe contacted the Tatarstan Health Ministry for comment but had received no response at the time of going to press.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]