Despite being just 24 years old, Andriy Kulko, a former PE teacher from Ukraine’s southeastern Zaporizhzhia region, has already experienced a great deal in life. Enlisting in the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) the year before the war started, he found himself in the inferno of Mariupol for three months in early 2022, where he was eventually captured by Russian forces. He then spent one year, eight months and 21 days being tortured in Russian captivity, a torment that only ended when he was returned to Ukraine in a prisoner exchange in January.

“I always wanted to be in the army or in law enforcement,” he recalls. “I suppose I had a heightened sense of justice.” He served in Ukraine’s National Guard and was stationed in the Donetsk region when the Russian invasion began in February 2022.

On the very first day of the war, Kulko’s company was deployed to Mariupol, where it soon found itself pinned down by the Russian military encircling the city. “I saw it all. Bombs hitting residential buildings. The bodies of dead civilians. The bodies of our soldiers. I helped get our lads out of the rubble,” he remembers.

In April 2022, Kolko was captured and taken to the notorious Olenivka prison camp, which made the headlines that July when a massive blast killed dozens of POWs. While Kulko had already been transferred to another camp by that time, he can nevertheless clearly recall the brutal beatings administered to him and his fellow POWs upon their arrival in Olenivka. “Six people beat us using different objects: wooden sticks, rubber truncheons, leather belts, and the like.”

Andriy Kulko before the Russian invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022.

Ryazhsk

From Olenivka, Kulko was taken to the southern Russian city of Rostov-on-Don, from where he was flown to the town of Ryazhsk in central Russia. There, he spent around 10 months in a detention centre before being transferred to a prison in the republic of Mordovia on 1 February 2023.

The Ryazhsk detention centre was frequented by Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) officers and investigators who tortured Ukrainian POWs to obtain any information they could and considered all prisoners captured in Mariupol to be “Nazis” and “terrorists” due to potential ties with the Azov Battalion.

“They asked me whether I killed soldiers, whether I killed civilians, and used all kinds of physical and psychological torture while they were at it,” he recalls.

“They’d put a plastic bag over your head and choke you. Then they’d beat you with rubber truncheons, punch you, kick you, taser you,” recounts Kulko. During interrogations, FSB officers would also violate Ukrainian soldiers with plastic tubes and torture them with electricity from a field telephone. “If you wire it up to certain parts of the body… they called it ‘putting a call through’. They’d turn the rotary dial, like on an old phone, and it would generate electricity,” he explains.

“They’d put a plastic bag over your head and choke you. Then they’d beat you with rubber truncheons, punch you, kick you, taser you.”

During the three months of the “investigation”, the prisoners were tortured almost daily. “Some couldn’t withstand the torture and said things that they shouldn’t have,” Kulko says. Those who confessed to committing “war crimes” under torture were taken to court in the Donetsk or Luhansk regions.

Many of Kulko’s fellow soldiers were given prison sentences, but Kulko managed to hold out without confessing to anything. “I think I just got lucky. That was the only option,” he says. After three months of interrogations the worst torture was over. “The rest was more tolerable,” Kulko adds.

Kulko after being captured. The photo on the left shows a group of Ukrainian POWs, including Kulko (R).

Mordovia

From Ryazhsk, Kulko and his fellow soldiers were sent to a penal colony in the Mordovian settlement of Udarny, where he was imprisoned until the swap that freed him in January.

Kulko claims that the torture in Mordovia was not as severe as in Ryazhsk, but the prison staff found all sorts of ways to abuse the POWs. “As soon as we arrived, they started beating and humiliating us. They stripped us naked and made us stand right next to each other. Then they took us to the investigator one by one where we were beaten head to toe and brought back to the cell. In the cell we were forced to stay on our feet for 16 hours a day.”

“Head down, eyes on the floor, hands behind your back. Every day for 11 months.”

Day after day, the prisoners had to stand in their cells from morning till night. Kulko recalls that the cells were equipped with surveillance cams. “Head down, eyes on the floor, hands behind your back. Every day for 11 months.”

Illustration: Alisa Krasnikova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

“If someone talked or moved without a command, or turned their head… The door would open and they would be taken away for a beating,” he says.

After one of the beatings, Kulko started having serious issues with one of his legs, which he says began to rot. The POWs did not receive any medical care. Doctors later told Kulko that the beatings had caused a blood clot to form in his leg, which restricted blood flow to the tissue above the ankle and which eventually led to it rotting. Despite this, Kulko continued to stand in his cell in an attempt to avoid even more severe beatings.

“One toe on my left foot stopped working. This also had to do with the fact that we were standing all the time, which meant fluid accumulated in the feet, leading to ulcers — holes, really. You could stick half your little finger in those holes. The surgeon told me that I was an inch away from blood poisoning,” Kulko says.

This is what Kulko’s legs looked like immediately after his release.

“I was in pain round the clock. I couldn’t sleep for weeks and began losing my mind. And then there were the suicidal thoughts, of course,” he admits. “But my cellmates kept my spirits up. And it was only with God’s help that I got through.”

Doctors would occasionally visit the prison, but rarely provided any medical care. “One doctor would ask if anyone needed a pill. But when you put your hand out, occasionally he’d taser you. I don’t know why. Sometimes he behaved normally and actually handed out pills. But occasionally something would click in his head and he’d taser your hand,” Kulko recalls.

Of the nine other prisoners with whom Kulko shared his cell, eight were also POWs while one was a civilian who had been captured on occupied territory.

“Even standing in there was a squeeze, not to mention walking around…The toilet had no doors,” Kulko recalls. “Toilet paper wasn’t always around. We only had a tiny tube of toothpaste for 10 people. It was horrid.”

“We figured out how to talk at least a little, as without talking you could really go crazy.”

The prisoners were allowed to use the toilet only on command, and sometimes not everyone could make it in time. If someone used it without permission, they would be taken away for another beating.

The prisoners were given three poor quality meals a day. “For breakfast we had porridge without salt or sugar, with one and a half pieces of bread. For lunch and dinner they gave us porridge and something similar to soup. Sometimes we got potatoes, but then the staff mentioned that those were meant for feeding animals. They had a weird taste, but we didn’t care what we ate.”

The prisoners were also forbidden from talking to each other, but they found ways to communicate clandestinely — by whispering and holding their heads down to conceal the movement of their lips. “You get used to everything,” Kulko says. “We figured out how to talk at least a little, as without talking you could really go crazy.”

They talked about anything and everything — cars, girls, books, movies… “I retold all seven Harry Potter books. I’m a big fan,” Kulko admits.

Illustration: Alisa Krasnikova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

“We tried not to lose heart, although it didn’t always work because we were constantly told: ‘Ukraine doesn’t exist anymore, no one is waiting for you, no one needs you’. Or: ‘We’ve only got to capture Lviv, and then there’ll be no Ukraine. Only foreign soldiers are fighting there — Americans, Poles, the French. None of your soldiers are left, we killed them all’,” he recalls.

Sometimes, Kulko begrudgingly admits, he was tempted to believe what the Russians were telling him. “I’ll be honest, there was a bit of Stockholm syndrome when you start to believe the terrorists. That happened from time to time. But then that sympathy passed, thank God. And after that, well, we were driven by hatred.”

After a while, new staff arrived at the prison and continued the beatings. “They had this big wooden mallet for checking cells. You’re supposed to use it on doorways, on the beds — if something is attached there, it will fall off. But they used it to beat us. We would go out into the halls, and they would beat us there,” Kulko recalls.

“We tried not to lose heart, although it didn’t always work because we were constantly told: ‘Ukraine doesn’t exist anymore, no one is waiting for you, no one needs you’.”

In an attempt to drown out the prisoners’ screams, prison staff would play loud music — but the screaming could still be heard.

“They would also set dogs on us. They forced us to crawl out of our cells and lie on the floor, and then the dogs would attack us, biting us until we were all bloody.”

The POWs were forced to sing the Russian national anthem eight times a day and learn Russian propaganda poetry — “thank God I don’t remember any of it anymore,” Kulko adds.

Some of the older officers treated the prisoners somewhat better — they did not beat them, allowed them to walk outside from time to time and permitted them to take longer showers. “Whereas the younger ones were completely brainwashed by propaganda about ‘murderous Ukrainians’ and beat us very badly,” Kulko continues.

One prison officer told Kulko about the existence of a document approved by the Russian Defence Ministry that detailed how to treat POWs and “destroy them physically and psychologically”.

Ukrainian POWs released in the January swap that Kulko was freed in. Photo: Volodymyr Zelensky’s Telegram channel

The prisoner swap

Until the very last moment, Kulko had no idea that he was being exchanged and thought that he was simply being transferred to another prison. On the evening of 2 January, he and his cellmates were removed from their cells, told to change into new clothes, had bags placed over their heads and were loaded into cars and then put on an aeroplane. Kulko only realised that an exchange was taking place when the bag was removed from his head at the border between the Russian city of Belgorod and Ukraine’s Sumy region.

During the exchange, Kulko saw the Russian POWs — “they were all clean, well-kempt, not thin. It was rather frustrating. But I am comforted by the thought that we have to adhere to the Geneva Conventions because we are human beings. Whereas the way we were treated is on their conscience.”

After the exchange, a Ukrainian officer approached Kulko and offered to call his parents. “I called them — there were tears, screaming, lots of joy… It was an unforgettable moment,” he recalls. “They were very happy, of course. But they didn’t believe it was me at first.”

Ukrainian POWs released in the prisoner swap with Russia on 3 January that Kulko was freed in. Photo: Dmytro Lubinets / Facebook

When asked what gave him the strength to endure the horrors of captivity, Kulko says: “Firstly, it was my parents. I considered suicide, but then I thought it would be devastating for my parents not to see me after I’d gone through so much in Mariupol. And secondly, my faith. Faith in something divine, you might say. Although I’m agnostic. I am Orthodox, I wear a cross, but nevertheless I consider myself agnostic”.

“I had hallucinations: I’d hallucinate lights or have music from the Russian prison constantly playing in my head.”

Upon his release, Kulko weighed just 55 kilograms — 20 less than his normal weight. He spent seven months in a Kyiv hospital where he underwent several surgeries. “They cut out a vein in my leg and several lymph nodes. My spine and the cerebral contusions also gave me trouble,” he recalls.

At first, he was unable to sleep at all for almost a week. “I had hallucinations: I’d hallucinate lights or have music from the Russian prison constantly playing in my head,” he says. “And I still keep having dreams about the war and my time in captivity.”

“I’ve been told that I’ll be fine if I visit a psychologist regularly. It just takes time,” he adds.

It’s now been a month since Kulko returned home to Zaporizhzhia. He’s now back to a healthy weight and is doing far better, but still has difficulty walking without a cane. He continues to serve in the military, doing administrative duties for the AFU.

“I think justice will eventually be served. I really hope it will.”

Kulko now plans to move to Lviv and get a second university degree in international conflict studies. “I have a lot of anger,” Kulko admits. “But I know I’m no use in combat anymore. So I think I’ll have to do something on an international level.”

Kulko has already given testimony to Ukrainian investigators, the security services, the International Red Cross, and the UN’s Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine about his experiences in Russian captivity, and says that though he finds it challenging to retell his story time and time again, he feels it is important.

“You have to inform people so that they know the truth about what’s really going on there. There are now multiple proven facts about what happens to POWs in Russia, so I think justice will eventually be served. I really hope it will.”

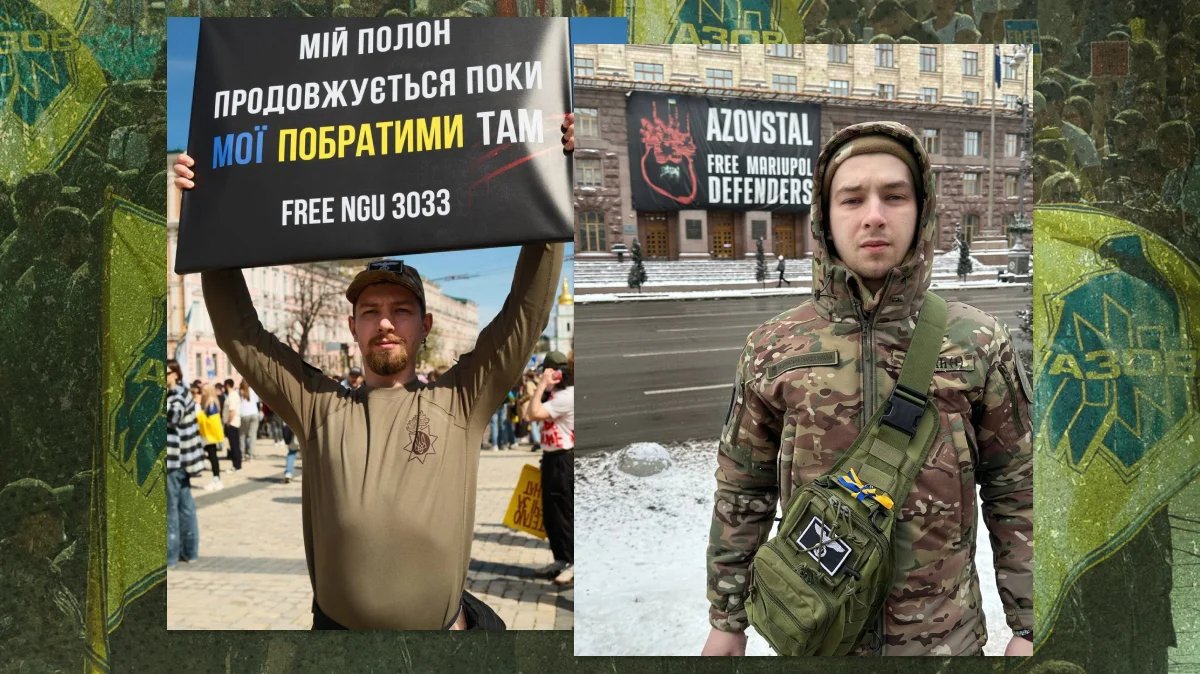

Kulko in Kyiv after his release. “My captivity continues while my brothers are there,” the poster on the left reads.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]