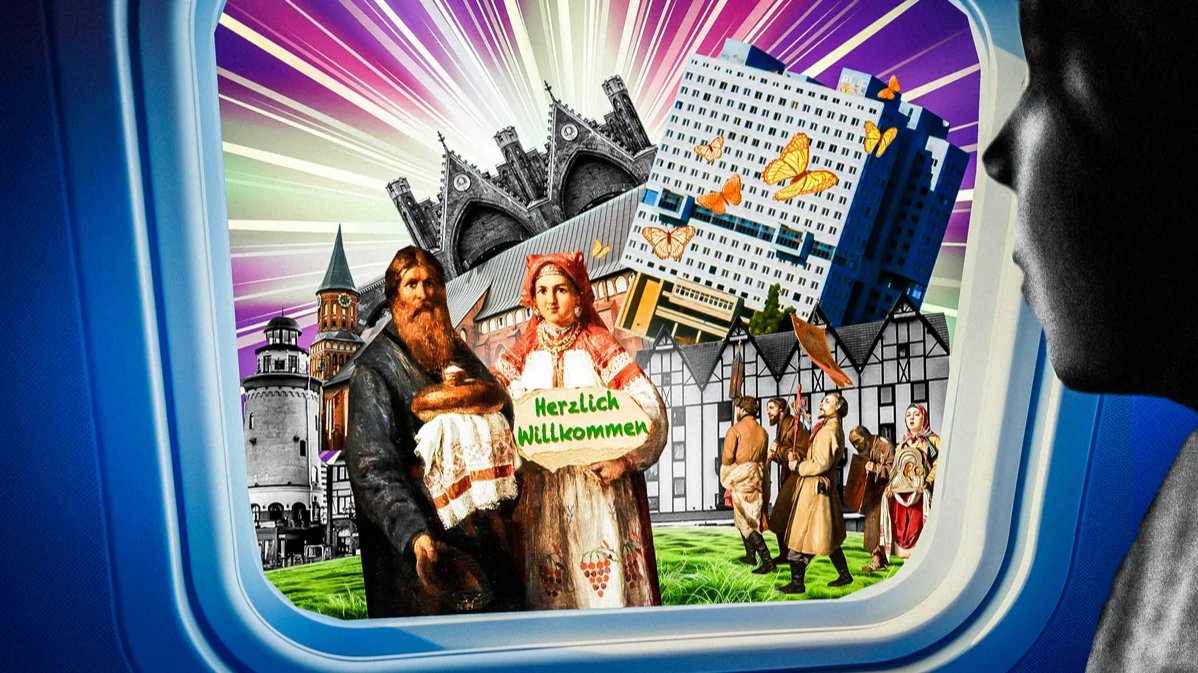

Local media outlets in Kaliningrad are abuzz with headlines such as “Germans fleeing to Kaliningrad” and “Germans are buying, Russians are afraid” as Russian Germans are reportedly buying up property in the Baltic exclave. YouTube channels now feature property tours for German buyers, and local real estate agents are eagerly awaiting wealthy investors from Germany. But are Germans really flocking to Kaliningrad, and, if so, why the sudden rush?

Journey to the West

A descendant of ethnic Germans who, due to a series of historical events found themselves strewn around the USSR, Yury, now 47, was born in Soviet Kazakhstan. When he was 21 in the late 1990s, he decided to move to Germany for a better life. There, he learned German, earned a second degree, started a family, and opened his own business.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, a reunited Germany launched a government programme allowing Russian Germans to return to the country and obtain German citizenship upon proving their language skills and kinship. Over 2 million Russian Germans left the Soviet Union throughout the 1990s and early 2000s to start anew in Germany. Yury was among them, but 25 years later, he and his wife are leaving Bavaria, Germany’s most economically successful region, to return to Russia.

“After much reflection, I came to the conclusion that this is not my native home,” Yury says. “I mean, of course, German society has become very familiar to me. I speak German well, but I still feel isolated and limited there all the time.”

Yury chose Kaliningrad primarily because of its geographical proximity to Germany, where his children have decided to stay.

“I think that most people choose Kaliningrad precisely because of its location: it’s a lot closer to Munich than Moscow, and even if it takes a while, you can still drive there to visit relatives,” he explains.

Kaliningrad, a Russian exclave nestled between Poland and Lithuania, was formerly the East Prussian city of Königsberg, until the Soviet Union seized control of it from the Nazis in 1945, later renaming it Kaliningrad. The German population was expelled and it was repopulated by Soviet citizens.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the exclave remained part of Russia while the neighbouring states of Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia gained independence.

Kaliningrad is still of great strategic and military importance for Russia, a key port city where weapons can be positioned within easy striking distance of Western Europe, it is also the headquarters of Russia’s Baltic Fleet.

A view of Kaliningrad's riverfront, 12 April 2018. Photo: Sergey Karpukhin / Reuters / Scanpix / LETA

A certain likeness

Local real estate agents confirm the increased demand for housing in Kaliningrad among German citizens. One such agent, Tatyana, told Novaya Europe that Russian Germans started contacting her in greater numbers a year and a half ago.

According to Tatyana, Russian Germans are buying property all over Russia, usually in the area they originate from. However, Kaliningrad is particularly popular among those who still have family in Germany. Another agent, Svetlana, believes that Germans prefer Kaliningrad in general.

“Why choose Kaliningrad? Because the city has a European feel. Perhaps it is psychologically easier for them to move there: it reminds them of Germany, but it’s Russian,” Svetlana says.

Russia has its own state resettlement programme designed to aid those who ended up outside the country after the collapse of the Soviet Union but now wish to return. In 2024, Vladimir Putin signed a decree establishing a repatriation institute. New measures introduced to encourage Russian Germans to return included relaxed language requirements and the freedom to choose any region in Russia for resettlement. However, social benefits available to Russian citizens at the federal level are not guaranteed for repatriates, and it's instead been left to individual Russian regions to determine what incentives to offer returnees.

Kaliningrad was the first region to start participating in the programme, and offers a one-off payment of 32,000 rubles (€335) per returning family member, along with reimbursement for various expenses, including up to six months’ rent for apartments costing less than 135,000 rubles (€1,400).

According to Russia’s Interior Ministry, 826,000 people participated in the relocation programme between 2006 and 2018. However, when the pandemic broke out, the numbers dwindled significantly. The lowest figure was recorded in 2023, when only 63,600 applications were received and just 45,000 people ultimately returned — half the number recorded in 2021.

Despite Russian media headlines boasting of an influx of returnees to Kaliningrad, official statistics tell a different story. In 2023, the number of migrants coming to Kaliningrad decreased almost threefold compared to 2021, falling from 16,000 to 5,000. In total, 54,000 people moved to Kaliningrad between 2007 and 2023.

A pro-war Z symbol on display in the Kaliningrad region town of Sovetsk on the Lithuanian border, 10 July 2023. Photo: Omar Marques / Anadolu Agency / Abaca Press / ddp images / Vida Press

Tempered expectations

Irina moved to Germany with her husband, a Russian German. They settled in Hagenow, a town between Hamburg and Berlin with a population of 11,000. Irina, accustomed to big city life, found the change in scenery challenging.

“Everything here is closed on weekends,” Irina says. “When you ride a bicycle, you can go 20-23 kilometres and not meet a single passerby the whole time. You see, Germany is empty.”

Irina says that her concerns aren’t just about the size of the city but rather the “mentality”. Her biggest gripe was with Germany’s healthcare system. She says she was shocked when a German ambulance refused to take her child to hospital when they came down with a temperature of over 41 degrees.

Irina says that her concerns aren’t just about the size of the city but rather the “mentality”

Six and a half years later, Irina and her husband bought land in Kaliningrad, where they are now building a house. When Irina first suggested the idea of moving, her husband was reluctant. On their initial visit, he had a negative impression of the city.

“My husband still doesn’t like the city very much, but I guess he’s gotten used to it. In Germany, I don’t know anything, and in Russia, he doesn’t. So here, for the first time, he will be following my lead. But I am determined,” she says.

Irina says that plots of land are “selling out” where they decided to settle due to high demand among migrants from Germany and the Baltic states.

An aerial view of Kaliningrad, August 2017. Photo: Tatiana Zenkovich / EPA

Targeted advertising

Valeria Dobralskaya, a German journalist and former resident of Kazakhstan, points out that there have always been Russian Germans who returned to Russia after long stays in Germany. The difference now, she notes, is the visibility afforded by social media. Many returnees document their entire journey online, sharing their experiences on platforms such as TikTok and YouTube.

“I think some of them … are intentionally running a media campaign as part of Russian propaganda. They depict a beautiful Russia untouched by war, with no persecution or oppression, offering better services, advanced technology, manicures on Sundays and so on,” Dobralskaya says.

Margo Zvereva, a TV presenter for Russian state-run TV channel RT DE, is one such influencer. She posts regularly on her social media about how superior the housing, healthcare, and government services are in Russia.

Liliia Sablina, a political scientist from Vienna’s Central European University, researches the media habits of Germany’s Russian diaspora. She notes that Russia ramped up its diaspora policy following it illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, investing in propaganda and programmes aimed at encouraging repatriation.

“Since 2008–2009, we’ve seen how ties with Russia started to strengthen, people started consuming more Russian content, because there is more Russian content in general,” says Sablina. She adds that interest in leaving Germany surged in 2015 and 2016 during the European migrant crisis, a period marked by a substantial increase in asylum seekers.

Two women kiss in front of a homophobic promotional poster for the far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD), Berlin, 23 July 2016. Photo: snapshot-photography / K M Krause / Shutterstock / Rex Features / Vida Press

A refuge for homophobes

Marina moved to Berlin 11 years ago, right after graduating from university in Russia at the age of 22. There she fell in love with Martin, a Russian German whose parents had brought him to Germany at a young age.

“We were very young and in love, everything was interesting: a new country, new language, life without our parents,” Marina says. “Of course, even then I was seeing gay people on the streets, it was strange to see, I just tried not to look.”

Marina recalls being ridiculed for making mistakes when she first tried speaking German with native speakers. Meanwhile, although her husband is fluent in German, he struggles with his identity, feeling he doesn’t fully belong in either Germany or Russia.

Her thoughts about returning to Russia became more pronounced after the birth of her children. Spending considerable time on parenting forums and chat rooms online, discussions often centred around Germany’s so-called “gender policy”.

Marina’s primary concern revolves around what she perceives as “LGBT propaganda” in Germany. She also asserts — with no evidence other than online hearsay — that Germany has become a “paedophile’s paradise” due to what she views as lenient sentencing for child abusers.

“I was very disturbed by this. In our kindergarten, half of the teachers are men. Because of this, I am under constant stress,” Marina laments.

The basic sex-education lessons provided in German schools are also perceived as “LGBT propaganda”. According to Sablina, Russian-speaking chat rooms in Germany frequently discuss the topic, with parents claiming that such propaganda is being imposed on their child.

“The chats only inflame these topics. That’s the whole point of social media. Perhaps without them people wouldn’t even think about LGBT propaganda,” Sablina says. “In the perception of people influenced by Russian propaganda, an LGBT person is almost like the Antichrist, a being that completely contradicts nature.”

It was this reason, as well as Marina’s desire to raise her children in a Russian environment, that prompted her to move.

“This is the last opportunity for our children to absorb the Russian culture, mentality, and traditional values. We realise that if they grow up in Germany, they won’t want to return. We want to instil different values in our children, and most importantly, avoid corrupting them,” she explains.

Entrance to a shop selling products from post-Soviet countries, Berlin, August 2017. Photo: dpa picture alliance / Alamy / Vida Press

Out of place

The most common reason for leaving Germany is that Russian Germans often feel they don’t fully belong. Despite their fluency in the language and familiarity with German society, many still live in Russian communities that were established during the first exodus to Germany in the 1990s.

“From what I see, they don’t feel that they are fully-fledged German citizens. They’re not Russians, but they are not Germans either. And they are deeply dissatisfied with this, despite their economic status,” says Sablina. “They lack the feeling of belonging to a big nation.”

Late repatriates, as ethnic German immigrants are known, are especially lured by Russian propaganda, capitalising on their longing for a sense of community. Sablina says the pro-Russian media campaign is working.

They’re not Russians, but they are not Germans either.

During the pandemic, many Russian Germans became involved in the anti-vaccination movement. Conspiracy theories circulated about the state’s vaccination programme, and when data on vaccine side effects emerged, it further fuelled scepticism among Russian Germans.

The introduction of universal vaccination and mask mandates in public places in Germany spurred Yury to contemplate relocating to Russia.

“There was real discrimination, you know? If someone came into a shop without a mask, they could be attacked or denounced,” Yury says. “In Russia, you had to wear masks too, but if you didn’t, nobody would attack you.” Novaya Europe was only able to confirm that Germany issued fines for violating its mask mandate.

A pro-Russian demonstrator at a Victory Day rally, Berlin, 9 May 2023. Photo: Caro / Schuelke / Scanpix / LETA

Plan B

Even those who speak fluent German, work for German companies and have never visited Russia are considering emigrating. Journalist Valeria Dobralskaya attributes this to Germany’s bureaucratic environment, which leads Russian Germans to believe their lives are over-regulated, sometimes overshadowing their considerations about Russia’s political regime.

“Many people feel that life flows differently in Russia, more easily, more freely,” she explains. “Nevertheless, we must not forget that many of these people have never been to Russia or have only visited tourist destinations. Therefore, they do not know the local realities and cannot say in all seriousness that in Moscow it is safe to go to Red Square with any sign and say whatever you want.”

Real estate agent Tatyana explains that even after moving, some individuals return to Germany because they don’t earn as much money in Russia.

Yury, who decided to move from Bavaria to Russia after 25 years, notes that having moved to Kaliningrad his life, of course, “did not immediately become paradise”.

“My German problems ended, and Russian ones began. So if someone flees hoping for an ideal life to start here, then, of course, it’s not like that,” he says.

All the names in this story have been changed.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]