Arrested when he attempted to enter Serbia last year after his name was added to Interpol’s wanted list for “tax evasion”, Belarusian director and anti-Lukashenko activist Andrey Gnyot has vowed to return to his homeland only as “a lifeless corpse”, knowing full well what awaits him if he goes back. Gnyot is currently under house arrest in Serbia while he waits for a court to rule on his appeal against his extradition, the final legal recourse available to him.

‘Western puppeteer’

Andrey Gnyot is one of Belarus’ most successful advertising directors, with an impressive track record of shooting campaigns for major Western brands. However, in addition to his creative success, he has always been politically active and unafraid to speak his mind. In 2020, he was labelled a “Western puppeteer” by none other than Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko.

In August 2020, as nationwide anti-Lukashenko protests shook Belarus, Gnyot co-founded the Free Association of Athletes with basketball player Yelena Leuchanka and handball coach Konstantin Yakovlev.

“Guys, I’m not an athlete, I’m a director, but I want to do something,” Gnyot recalls telling his colleagues. “There are lots of you, you have an impeccable reputation, you can become the engine. We can demoralise the dictator so badly, he’ll be devastated.”

The athletes filmed video messages that Gnyot then posted online, which ultimately led to the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) cancelling its plans to hold that summer’s world championship in Belarus, a personal blow to Lukashenko, who is a well-known hockey fanatic.

To avoid being caught by police, Gnyot uploaded protest videos to Instagram from a relative’s summer home. For nine months, he managed to remain under the radar of the country’s law enforcement agencies, but then in June 2021, he received a summons from the Investigative Committee.

The summer of 2021 was a tumultuous time for Belarus marked by daily arrests, the shuttering of independent media, and numerous trials and convictions. Those who had not yet left were packing up in a hurry, and the two lawyers Gnyot knew both advised him to pack his bags and leave the country while he could.

Lacking a Schengen visa, Gnyot decided to head to Moscow, where he had friends and believed it would be easy to hide. He packed his bags in two hours and left.

Protests in Minsk. Photo provided by Andrey Gnyot

Two emigrations and one extradition

Gnyot spent just six months in Russia. In December, he left for a holiday in Thailand, intending to return on 25 February 2022. However, as Russia invaded Ukraine the day before he was due to travel, he decided not to return to Moscow.

Ironically, it was his own idea to film an advertising campaign in Serbia in October, having already visited the country a few months earlier to shoot an advert for Danone.

A border guard scrutinised his passport for an unusually long time upon his arrival at Belgrade Airport on 30 October. Another guard was eventually called over, and soon a police officer appeared and asked Gnyot to accompany him.

Unsure what to think of the situation, Gnyot recalls that despite realising that he had been caught, he attempted to comfort himself by repeating that he wasn’t some kind of Julian Assange-like figure “to be hunted down”.

“I was accused of paying taxes incorrectly between 2012 and 2018, violating amendments to the tax code that were only adopted in 2019!” he says.

After eight hours, a police officer asked Gnyot if he had a lawyer. After messaging his producers and assistant, Gnyot miraculously found two, despite it being so late in the day. He was scheduled to meet them in court the same evening, but was first taken to a police station where he was informed that Belarus had requested his detention and extradition through Interpol, a request the police in Serbia were legally obligated to fulfil.

Photo provided by Andrey Gnyot

The judge ordered Gnyot be held for 40 days in a central Belgrade prison while Belarus sent the necessary extradition documents. The director couldn’t fathom spending 40 days in prison, unaware that his time behind bars would stretch far beyond that.

The documents arrived two weeks later, 30 pages of text including a petition from the General Prosecutor’s Office of Belarus to the Serbian Ministry of Justice which began with assurances that Gnyot would not face persecution on political grounds in Belarus, nor would he face cruel treatment, and that all international norms would be upheld. The paperwork also contained excerpts from the criminal case, which finally gave Gnyot an insight into the charges he faced.

Aware that Interpol is unlikely to action requests from Minsk based on political charges, Belarusian law enforcement finds that the most effective method to extradite individuals fleeing political persecution is to accuse them of financial offences. From his case file, Gnyot learned that he had been accused of tax evasion in Belarus.

“I was accused of paying taxes incorrectly between 2012 and 2018, violating amendments to the tax code that were only adopted in 2019!” he says.

“When I finished reading, I calmed down,” he recalls. “I understood that it was revenge, for the athletes, for the fact that we had achieved the cancellation of the World Hockey Championship in Belarus, and that I had not committed any crime.”

From extradition to appeal

Neither Gnyot nor his lawyers were notified about the secret court hearing to rule on his extradition on 7 December, though the court is required by law to hear from the extraditee and their defence team to establish what obstacles to extradition there might be.

Gnyot was given no opportunity to plead his case. In mid-December, he received the court’s decision to extradite him without being heard. His lawyers promptly filed a complaint with the Court of Appeal, citing a violation of Serbian law. On 19 February, the extradition issue was re-evaluated from the beginning.

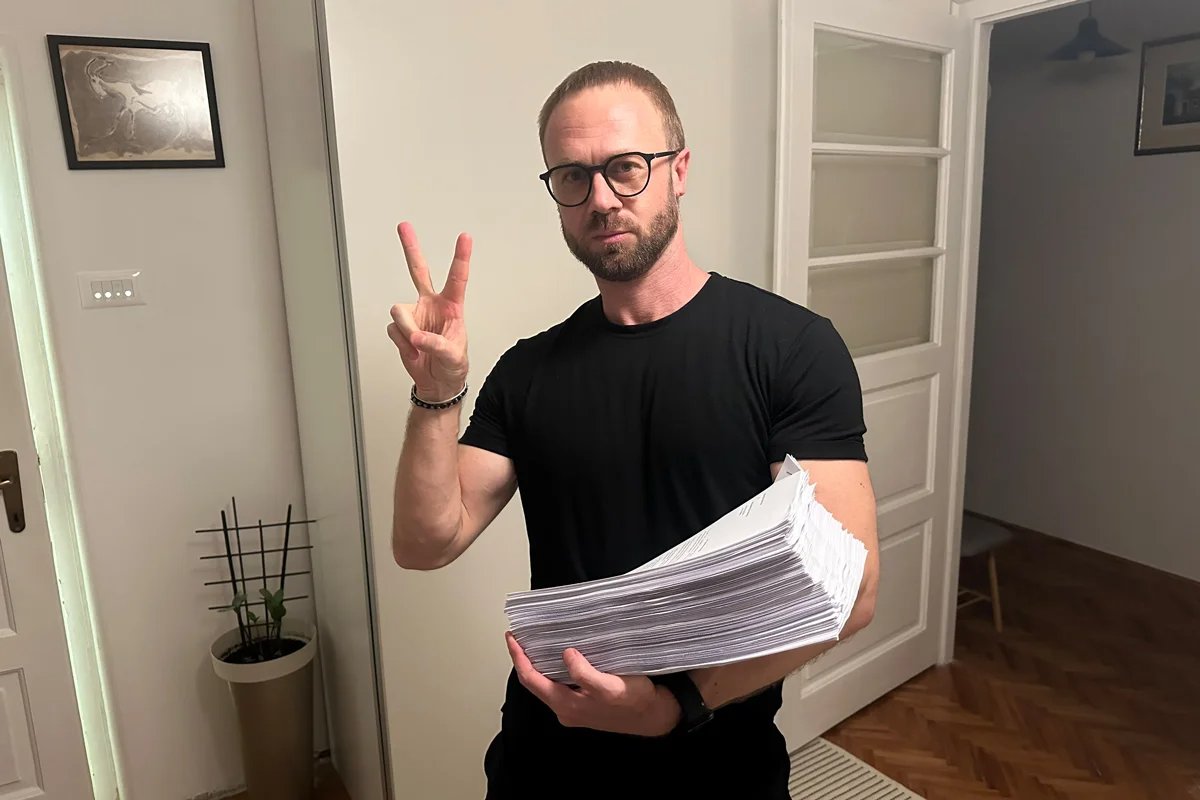

There were two more court hearings in the spring, at which Gnyot provided evidence that the charges against him were politically motivated. “In total, I attached about 200 pages to my pleadings. It took the court up to two months to read it all, and on 31 May, the High Court ruled that all the conditions for my extradition were met and there were no obstacles,” he says.

Gnyot carrying his case files. Photo provided by Andrey Gnyot

“Both Belarus and Russia are full-fledged members of Interpol, and co-operation continues,” says Belarusian lawyer Ales Mikhalevich. “One should understand that Interpol is the second largest international organisation after the UN. Of course, it includes both totalitarian and authoritarian states in large numbers.”

However, a citizen of Belarus or Russia will not get onto the Interpol wanted list for extremist articles, which are most often politically motivated. “It won’t pass the sieve of checks,” says Mikhalevich. “But if the charge is financial, it’s easy.”

Mikhalevich believes that Belarus is unlikely to succeed, but Gnyot is still waiting for the results of his second appeal against the court decision to extradite him, this time from house arrest rather than confined to a prison cell.

*

Gnyot wears an electronic bracelet on his ankle that monitors his movements, allowing him one hour outside per day. However, there are no restrictions on visitors, and so despite his situation, he manages to remain cheerful. He enjoys the borscht human rights activists bring to him, but is adamant that he will not return to present-day Belarus alive, saying ominously, “they won’t get me.”

Gnyot’s electronic bracelet on his ankle. Photo provided by Andrey Gnyot