Fifteen-year-old Arseny Turbin, from the town of Livny, in western Russia’s Oryol region, was sentenced to five years in prison for terrorism on 21 June. Though he excelled at maths and was fascinated by physics and tech, he had planned to study political science, in an attempt to better understand what was happening in Russia and with the hope that it would teach him how to improve the situation further down the line. But instead of going to high school, he now finds himself in prison, and when his erstwhile friends go on to higher education, he’ll still have three years of his sentence left to serve.

‘Don’t you worry’

The doorbell rang at the Turbins’ flat at 6am on Tuesday 29 August of last year. The summer holidays were drawing to a close and Arseny was fast asleep. His mother, Irina, went to open the door. His grandparents wondered who on earth it could be at that time. “FSB,” voices on the other side of the door said.

“It was the first time I’d come across FSB officers,” Irina Turbina explains. “I never realised how dishonest they were.”

They had come with a search warrant.

“They didn’t lay a finger on Arseny,” Irina says, her voice quavering. “I woke him up and he sat there on the couch, with his hands on his lap. They said: ‘You posted a photo of Putin with his face crossed out on your VK page. Is that your way of showing what you think of the president? Why do you do it openly, in your own name? Aren’t you afraid?’ He said: ‘No, I’m not afraid. I’m not breaking any laws.’ And he said to me, ‘Don’t you worry, mum. Everything will be OK. I didn’t do anything wrong.’” The officers left, taking his phone, tablet and laptop with them.

Three days later, Arseny started ninth grade. Within days, on 5 September, the FSB appeared at the Turbin home again with another search warrant.

“That morning, Arseny went to school, and I went to the balcony to wave him off,” says Irina. “I saw a car pull up. Two men got out, stopped Arseny, turned him round and led him back towards the house. I ran out and they showed me their ID.”

Arseny and his mother

Terror by proxy

Turbin was charged with involvement with a terror organisation. According to the investigation, in the spring of 2023, Turbin had repeatedly viewed material online posted by politicians who opposed Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

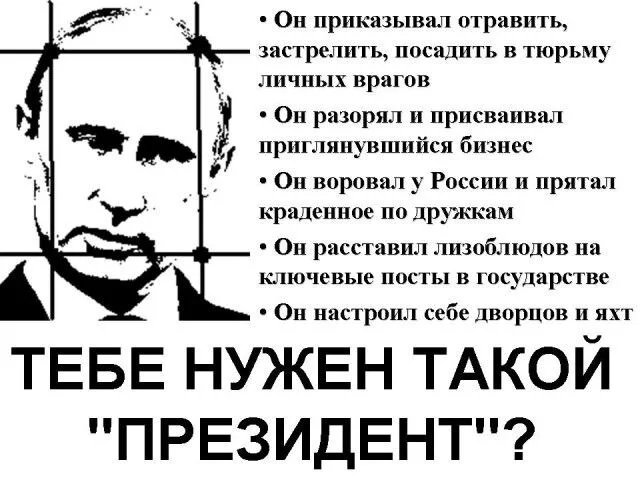

In June, Turbin had printed off “about 100 leaflets painting a negative picture of the Russian president” and dropped them in mailboxes within a five-minute walk of his home.

The Putin leaflet

The leaflet read: “He ordered his enemies to be poisoned, shot and jailed. He gutted and embezzled businesses he took a liking to. He stole from Russia and stashed his ill-gotten gains with his cronies. He put sycophants in key government positions. He built himself palaces and bought yachts. Do you need such a ‘president’?”

A hard copy of the leaflet was the one thing the FSB officers had been unable to find at the Turbins’ home, but they ended up finding the key piece of evidence almost by chance. As Arseny and his mother were being taken to the police station for questioning in September, the officers stopped off at one of the addresses where he had posted the leaflets back in June, and found one just lying there.

“In court, Arseny said he hadn’t hidden what he was doing as he didn’t think he was breaking the law, just expressing an opinion,” Irina says. “He always made it clear that he stood for a peaceful transition of power and for free and fair elections. He just wanted to inform people what was happening.”

The Investigative Committee petitioned the court to keep Turbin in custody due to his “dangerous” status, but the court ruled he should still be allowed to attend school, so he prepared for his exams while under house arrest.

But the FSB saw another motive. In their view, Turbin, dissatisfied with the Russian state, had decided to join the paramilitary Freedom of Russia Legion, which fights alongside the Armed Forces of Ukraine against the Russian military, and which has been designated a terrorist organisation in Russia. He found their email address and exchanged messages with a recruiter. The recruiter sent him a questionnaire that all potential volunteers receive to assess their willingness and ability to contribute to the legion. The investigation argued that sympathy with the group was the sole possible explanation for Turbin’s correspondence.

“Arseny did download the questionnaire,” Irina freely admits, but that is as far as it went. Arseny was charged with involvement with the organisation, without being a member.

Since Arseny is a minor, the criminal case against him was conducted by the Oryol region Investigative Committee. After the second search of the Turbin home on 5 September, he was held, taken to Oryol and placed in pretrial detention. The Investigative Committee petitioned the court to keep Turbin in custody due to his “dangerous” status, but the court ruled he should still be allowed to attend school, so he prepared for his exams while under house arrest.

It takes a village

Arseny grew up with his mother and grandparents.

“He wasn’t like other children, even when he was very young,” says Irina. “When he was little, he used to take me to a bookstore to buy books for him. He loved encyclopaedias. … Then he got into physics … And little Arseny loved mathematics too.” But, once at school, he didn’t like his maths teacher. Irina found a tutor for her son, who discovered he could already solve complex mathematical problems. It was school that was the problem.

Things came to a head when a group of boys laid in wait for Arseny as he left school on 28 November, knocking him to the ground and beating him up.

Years later, nothing had changed. In November, he was forced to leave school, as news had got out that Arseny was a “criminal”.

“It was a nightmare with his teachers. One, Yelena Kuksa, advised the head on pastoral matters. She showed the other children something about Arseny’s case. The head and deputy head went from class to class telling pupils not to communicate with Arseny Turbin as he had been declared a foreign agent, which was nonsense! I went and asked the FSB how the school knew about the case. They said they had no idea.”

Things came to a head when a group of boys laid in wait for Arseny as he left school on 28 November, knocking him to the ground and beating him up. He got away, ran into the nearest building and began ringing on all the doorbells. Two women came to his rescue. One ran out and shouted at the boys, the other began filming and threatened to hand the footage over to the police.

Irina home-schooled her son from then on. His friends stuck by him for a couple of months, but then contact dried up. Arseny then heard that the investigator had asked them to testify against him. One of them told Irina that they were promised a good grade in their exam if they cooperated.

Accusers and accused

Turbin was 14 when the investigation began. In most cases, criminal liability in Russia starts at 16, but in 2016, the lower house of Russia’s parliament, the State Duma, lowered the bar for certain types of crime. Children could now be declared terrorists from the age of 14. Arseny was somewhat unlucky concerning the legion too. Russia had only declared it a terrorist organisation two weeks before he downloaded the questionnaire.

“When they took Arseny and me to see the investigator, I was hysterical,” Irina says, struggling to hold back tears. “I was crying and shouted at them, asking if they’d gone mad, acting this way with a child. Couldn’t you have just spoken to him? He’d have stopped!”

“If we’d known how dishonest they were, we’d have reread the entire statement,” says Irina. “But we thought they’d just corrected the surname.”

A stumbling block from the investigation’s point of view was that he hadn’t filled in and returned the questionnaire. Arseny was interrogated by the FSB the day after the first search, on 30 August. He was accompanied by his mother, as a 14-year-old cannot be interrogated alone. He told the officers that he hadn’t joined the legion. They carefully recorded his answers and then gave the Turbins a statement to sign. Arseny noticed a typo in his surname. They praised him for noticing the mistake and corrected it, but when they went to print out the corrected statement, the printer wouldn’t work. The officers printed it out in another room. When they came back with the statement, Irina and her son made sure that the surname was now spelt correctly and signed their names.

“If we’d known how dishonest they were, we’d have reread the entire statement,” says Irina. “But we thought they’d just corrected the surname.”

Only in court would they realise that Arseny’s testimony had been rewritten. The new statement said he had sent the questionnaire back to the legion.

Three prosecutors upheld the charges against the teenager. Two teachers from Arseny’s school and five of his friends were summoned as witnesses.

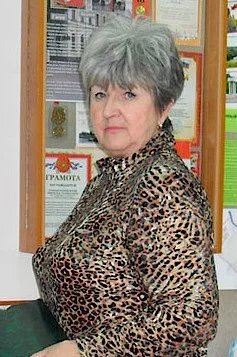

Valentina Abramova, head of pastoral care. Photo: Bulgakov Lyceum, Livny

Pastoral care head Valentina Abramova said she had long been aware of “Turbin’s statements against the government and the Russian president”, though corrected herself to say “as she had heard from teachers and pupils”. Abramova, a teacher of Russian language and literature, has 58 years of professional experience.

Witness Alina Nesterova taught Arseny social studies. She also teaches English and works as a tutor, although her online reviews are less than flattering. She qualified as a teacher in 2023, meaning this was her first full academic year. She testified that “the defendant made statements in social studies lessons which discredited the government and the Russian president”.

Four former classmates who were supposedly Arseny’s friends also testified against him, telling the court that he “regularly spoke out at school against the government, the Russian president and the special military operation”.

Another boy, Lev Kalugin, said he had been asked to “film the defendant distributing leaflets to people’s mailboxes”. He added that “Turbin had a negative view of the Russian president and spoke out against the special military operation”.

The judge in the case, Judge Oleg Shishov, had already handed down 13 sentences on terrorism charges in the last year. Turbin’s was his 14th, and there are four more cases currently pending. Shishov works quickly. The entire judicial examination of the Turbin case took just three days. The fourth and final session began with the prosecution and defence stating their cases. Shishov then retired to deliberate. He was back with his verdict three hours later.

The court took into account an array of circumstances potentially mitigating Turbin’s guilt: his lack of previous convictions, the fact he grew up without a father, even the fact that he had voluntarily handed over the passwords to all his devices. Nonetheless, the court felt it could not ignore the “public danger” the crime presented and the need for a custodial sentence. On 21 June, Judge Shishov therefore ruled that Turbin should serve five years in a juvenile prison, making him Russia’s youngest current political prisoner.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]