When 37-year-old Finnish resident Voislav Torden was detained at Helsinki airport last year after various inconsistencies between his Finnish residence permit and Russian passport raised suspicions with immigration officers, a year-long test of the West’s commitment to transitional justice in Ukraine ensued.

Dan White is a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and a former officer in the US Army.

It turned out that the Finnish authorities had stumbled across the latest alias being used by Yan Petrovsky, a militia commander and a leader of Russia’s far-right who has been sanctioned by the US for his suspected involvement in war crimes in Ukraine.

The case deserves greater attention than it has so far received as Petrovsky embodies the transformation of Russia under Vladimir Putin into an expansionist, authoritarian state. The struggle to put Petrovsky on trial is also illustrative of the broader struggle between Ukraine and the European Union to reach a shared understanding of the threat posed by Russia’s imperial ambitions, and the steps needed to confront it.

Rusich has been active since at least 2014 and is known for its embrace of neo-Nazi symbols and ideology, social media savvy, and advocacy of violence and sadism.

Before he was arrested, Yan Petrovsky served as the second in command of the Russian neo-Nazi paramilitary group Rusich. The group, co-founded by notorious psychopath Alexey Milchakov, has been active since at least 2014 and is known for its embrace of neo-Nazi symbols and ideology, social media savvy, and advocacy of violence and sadism.

From 2014 to 2015, Rusich militants led by Petrovsky and Milchakov fought in Russia’s hybrid war in Donbas alongside the militias of the “Luhansk People’s Republic”. The group is suspected of involvement in various war crimes including the brutal execution of at least 18 Ukrainian prisoners of war captured in an ambush near the city of Metalist in 2015. Petrovsky himself has openly admitted to his involvement in these atrocities and has repeatedly advocated the mass murder of Ukrainians.

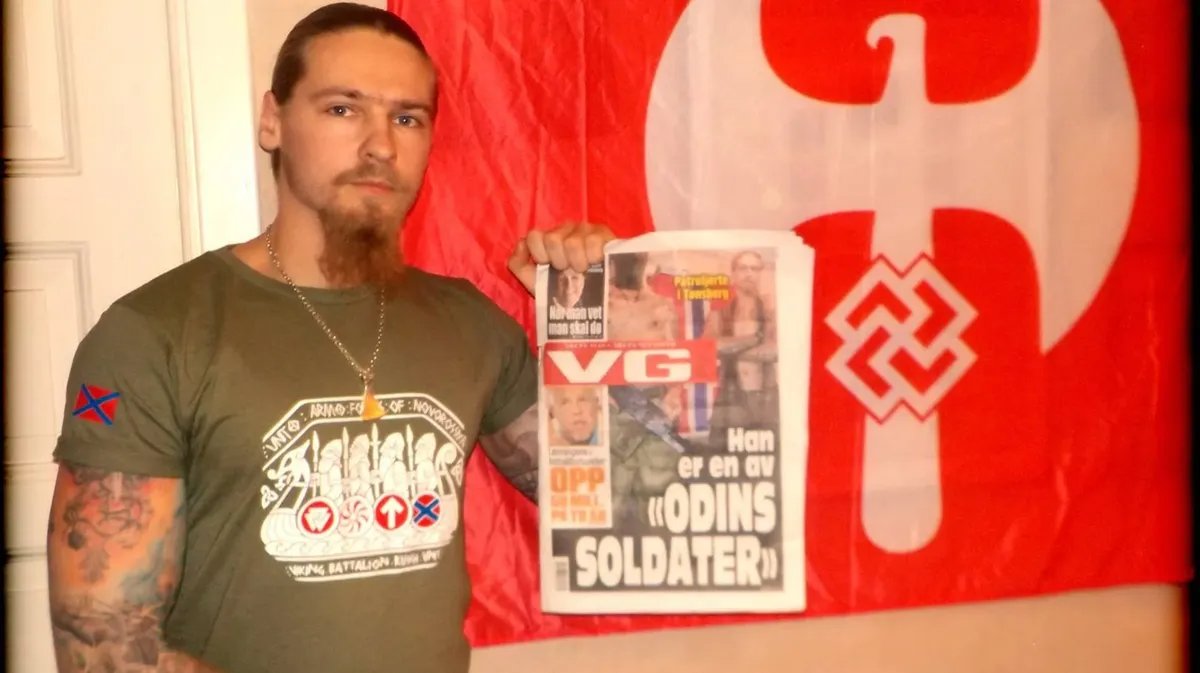

Yan Petrovsky in a frame from a Rusich training video

After the freezing of the hybrid war in Donbas, Petrovsky and other members of Rusich turned their attention to conflicts elsewhere, supporting the operations of Russian private military companies — including the Wagner Group — in Syria and Sierra Leone. Members of Rusich are widely believed to have been involved in various murders, including the infamous killing of Syrian Army deserter Hamdi Bouta.

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Petrovsky and a detachment of Rusich fighters returned to fight there, seeing active combat near Kharkiv. During this time, units under Petrovsky’s leadership appear to have been complicit in war crimes in the Ukrainian cities of Vovchansk and Izyum.

Rusich is not the largest, nor most distinguished Russian paramilitary group, yet it is one of the most recognised, in part because of its high profile on social media. Rusich has cultivated its outsized influence in part due to its unusual frankness about its brutality. Since the start of the full scale invasion, members of Rusich have posted videos of prisoner executions and the coercion of captured Ukrainian officials, published instructions on torture, and have even claimed to extort the family members of Ukrainian prisoners it has killed for information on the whereabouts of their loved one’s remains.

This brazenness has helped Rusich accumulate over 196,000 followers on Telegram and over $100,000 in cryptocurrency donations since the start of the war. The attention has also made Petrovsky something of a figurehead for Russia’s so-called “turbo patriots.”

Since the start of the war, numerous Russian ultranationalist leaders have risked travelling to Ukraine for the chance to be seen touring the battlefield with Petrovsky. These include State Duma Deputy Alexander Borodai, the former leader of the now defunct Novorossiya project; Alexei Zhuravlev, the first deputy chairman of the State Duma Defence Committee; and ultra-Orthodox oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev. These powerful patrons in turn appointed Petrovsky to a position of influence within the Union of Donbas Volunteers, a much larger grouping of pro-Russian paramilitaries.

Shortly after Petrovsky’s arrest, Ukraine submitted a request to the Finnish authorities to extradite him to face charges for crimes against humanity, only to have it denied by Finland’s Supreme Court. The court’s decision was based on an assessment by the European Court of Human Rights that Petrovsky would likely be subjected to abuse by both fellow inmates and prison guards, meaning that his extradition would violate his human rights. Instead of standing trial for war crimes, Petrovsky was prosecuted for entering Finland illegally and given a 40-day suspended sentence.

Yan Petrovsky. Photo: Rusich

Finland has since opened its own investigation into Petrovsky’s alleged involvement in war crimes, possibly in response to international criticism of the Supreme Court’s refusal to extradite him. But even if Finland decides to try and imprison Petrovsky under universal jurisdiction, it is far from clear that European courts will render a satisfactory verdict themselves.

Ukraine’s European partners have already failed to bring Petrovsky to justice when they had the chance in the past, deporting him to Russia after his arrest in Norway in 2016, despite the fact until weeks before his arrest he had been involved in the training of child soldiers for combat in Donbas, and patrolling Norwegian streets with local far-right thugs to intimidate immigrants.

Ukraine should be given the opportunity to demonstrate its capacity to administer justice in accordance with the standards set by its European partners.

The concerns about unsatisfactory conditions in Ukraine’s prisons which prompted Finland to deny Petrovsky’s extradition are valid. However, they are also an issue which Ukraine has recognised and made a concerted effort to tackle, despite being at war, in its quest to join the European Union. According to the European Council’s own report, “Ukraine has made progress on the rule of law as well as on judicial and administration reform.”

Ukraine should therefore be given the opportunity to demonstrate its capacity to administer justice in accordance with the standards set by its European partners. Petrovsky, a man who has been enabled to serve as an instrument of Russian foreign policy due to the culture of aggression, illegality and impunity cultivated under Vladimir Putin, would be an ideal starting point for this venture. The sight of Petrovsky facing justice in Ukraine would be a major step forward in dismantling the cultural foundations of Putin’s imperial project and asserting the primacy of Ukrainian self-determination.

Views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of Novaya Gazeta Europe.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]