Alexey Schwarz’s political awakening began with his own environmental activism, which allowed him to observe government corruption up close. His subsequent decision to work for Alexey Navalny’s headquarters in his native Kurgan set him on a collision course with the Russian authorities that would eventually force him and his family to go into exile in Germany.

‘I was born in the gulag’

The village of Zelenaya Sopka where Alexey Schwarz was born in 1996, is home primarily to descendents of ethnic Germans who settled in Russia after being displaced after World War I from what had been the German Empire. “I was born in the gulag,” Schwarz told Novaya Gazeta Europe. “It was created back in the Russian Empire specifically for exiled Germans.”

Schwarz’s ancestors were subjects of the German Kaiser before World War I. Along with Germans from East Prussia, they were forcibly expelled and took refuge in the Kurgan region near Russia’s border with Kazakhstan.

Ethnic Germans living in Russia during World War II were frequently branded enemies of the state and sent to hard labour camps. Schwarz’s family was no exception.

Those who fled Germany were forced to endure incredibly harsh conditions, which included being forbidden from cutting down trees or building new homes. As a result, many dug dirt shelters underground to survive. “My grandfather was born in such a dugout, I saw it,” Schwarz said.

Ethnic Germans living in Russia during World War II were frequently branded enemies of the state, had their homes seized, faced residency and travel restrictions, and were often sent to hard labour camps, and Schwarz says his family was no exception. “My great-grandfather’s children were taken away from him in Zelenaya Sopka; my grandfather, his brother and sister were sent to be raised by another family.”

He remembers his grandfather describing the family’s immense suffering under Stalin, the brutal imposition of collectivisation and the famines that ensued. Though many Russian families experienced similar hardship and brutality in that period, the generational trauma in Schwarz’s case led him to political activism and eventually to work for late opposition politician Alexey Navalny during his 2018 attempt to run for president.

Becoming an activist

Schwarz attended Kurgan State University and obtained a degree in natural sciences. During his time at university, Schwarz became an environmental activist and focused particularly on uranium mining near Kurgan.

Before the Kurgan region’s recent bout of floods, Schwarz attempted to warn authorities that uranium mining along the local Tobol floodplain would be dangerous, costly and unrealistic. As part of his mission, Schwarz travelled to villages near uranium deposit developments, captured video footage of their progress and uploaded the footage to YouTube. Schwarz was able to disrupt public hearings organised by Russia’s atomic energy agency Rosatom that sought to convince citizens that mining uranium posed no danger to local residents.

His environmental activism and the state corruption he encountered along the way put Schwarz on a path of conflict with the Russian authorities. This was compounded in 2017, when Schwarz was awarded a state grant for a physics project he proposed worth 2 million rubles (over €30,000 at the time). According to Schwarz, the grant commission told him to return half the sum to them in cash as a bribe. When he refused to pay the “commission”, the grant was immediately revoked.

For Schwarz the personal cost of state malfeasance, coupled with his frustration at the government’s environmental agenda, convinced him that Russian state corruption was an ever-present danger.

Shortly after graduating, Schwarz began to watch Navalny’s popular Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) videos and speeches on YouTube. “I suddenly understood that his words perfectly expressed what I had been feeling but couldn’t articulate,” Schwarz told Novaya Europe.

Alexey Schwarz with Alexey Navalny. Photo: Facebook

“Not a week went by without police coming for me.”

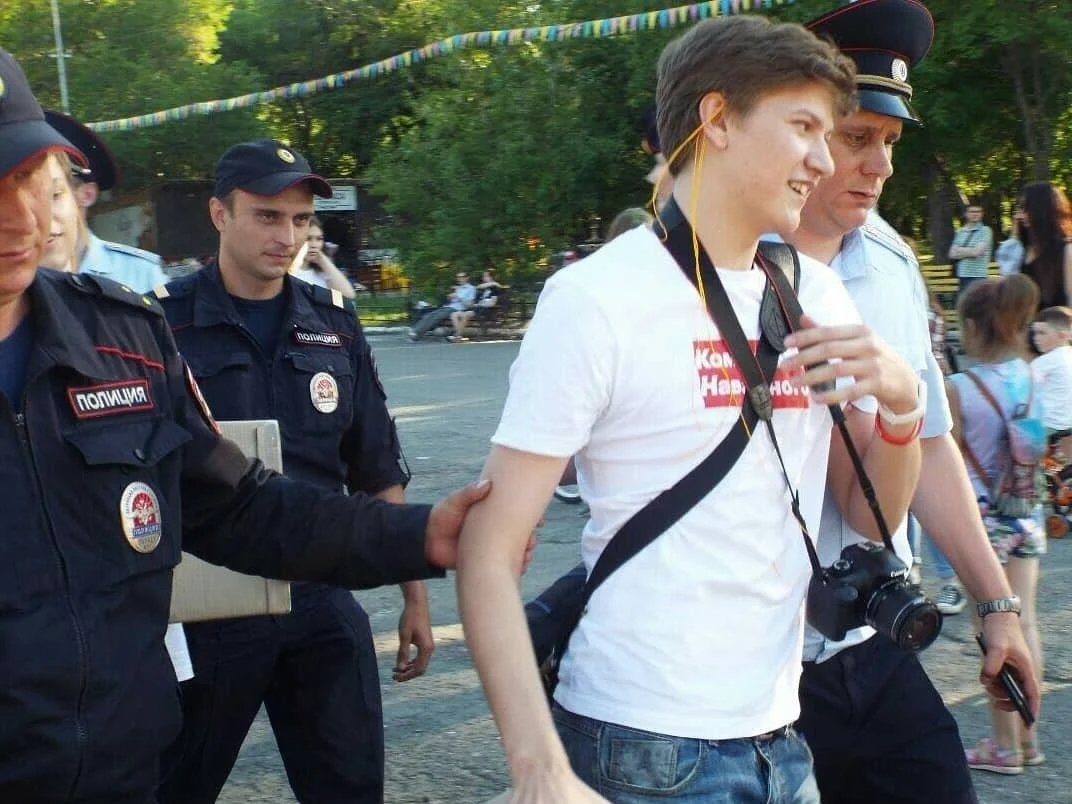

Schwarz joined Navalny’s campaign headquarters in Kurgan in the summer of 2017, and it was at a campaign event for Navalny’s presidential bid the following year where he was detained for the first time.

Following his detention, Schwarz became even more deeply committed to the campaign, organising rallies on Navalny’s behalf, attending political and legal hearings, publishing election pamphlets and working as an election observer.

In 2019, Schwarz was asked to head Navalny’s headquarters in Kurgan. “I earned myself a nervous tic from this work,” he said. The role was very challenging given the political atmosphere, and Schwarz was arrested several times on the job. “Back then, not a week went by without police coming for me,” he said.

Alexey detained by the police during an opposition rally in Kurgan on 1 July 2018. Photo: Facebook

Political interrogation

In an attempt to discredit Schwarz with a criminal prosecution, the authorities alleged that he had been involved in a bribery scheme at his university. The charges were dropped after it emerged that Schwarz had recorded a meeting with his professor in which he flatly refused to pay him an expected bribe.

After the bribery allegations failed, the police accused Schwarz of evading military service. Although Schwarz is partially blind in one eye and deferred his application for a mandatory military ID. Authorities maintained that he needed to have gone directly to the military registration and enlistment office to report his vision impairment.

Schwarz recalls being interrogated about his military service on 20 August 2020, the day that Navalny was poisoned with a nerve agent while on a flight from Tomsk to Moscow.

“I realised that I could lose everything overnight.”

Although Schwarz tried to explain his circumstances to the authorities, the case was opened anyway and, in the fall of 2020, Schwarz remembers attending daily interrogations with investigators. In one interrogation on 30 December, masked soldiers broke down Schwarz’s door, knocked him to the ground and forced him into a car to be taken to a private clinic. There, Schwarz was dragged into a doctor’s office to be examined and, as the police hoped, to be declared fit for military service.

But the doctor at the clinic refused to comply with the police. Schwarz recalls the doctor speaking to the investigator: “What the hell is the army doing? He should be registered as having a disability.”

Both attempts to charge Schwarz with a crime failed. However, the lack of control Schwarz felt over his own life and the unpredictability of the Russian authorities left a lasting impact on the young activist. “I realised that I could lose everything overnight,” he told Novaya Europe.

The road to exile

In January 2021, Schwarz was handed an audio recording by an anonymous individual who worked in the Kurgan government, detailing how voting results in the region had been falsified by regional officials including its deputy governor.

Schwarz with a lawyer outside the courthouse after a hearing on a criminal case for revealing the recording. Photo: Facebook

After verifying the recording, Schwarz called each individual from the recording posing as the assistant to the presidential envoy to the Ural Federal District. He videotaped the entire process, during which Schwarz said “they all actually confessed”.

“They used the same methods on me that were later used on Navalny.”

When Navalny was detained at a Moscow airport upon returning to Russia in January 2021, a series of protests saw thousands of his supporters take to the streets across Russia. Schwarz organised a rally for Navalny in the Kurgan region, and even though he didn’t attend the rally himself, Schwarz was arrested for his role organising the protest.

“They used the same methods on me that were later used on Navalny,” Schwarz recalled, adding that in the special detention centre where he was held, “the light was always on in the cell, day and night.”

During Schwarz’s arrests and jail time, his parents were both fired from their jobs and forced to leave the region in order to find new work.

It quickly became apparent that staying in Russia was no longer possible. Shortly after being released from the detention centre Schwarz, his wife and his parents fled to Ukraine across the border on foot, arriving there shortly before Russia invaded on 24 February 2022.

“I still have nightmares: I’m fleeing Russia, but I know that I won’t be able to escape.”

In January 2022, Schwarz and his family left Ukraine for Germany, where they had been granted political asylum. Schwarz received extensive physical and mental health treatment in Germany for the harm he suffered while in Russian detention. “I still have nightmares: I’m fleeing Russia, but I know that I won’t be able to escape.”

Schwarz at a collection drive for humanitarian aid for Ukrainians in Germany. Photo from his personal archive.

In October 2023, the Kurgan city court found Schwarz guilty in absentia of spreading misinformation about the Russian army and sentenced him to six years in prison. It’s now certain that Schwarz will be unable to return to Russia while Putin remains in power and the Kremlin continues to intimidate, imprison and kill its political opponents.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]