Russians need courage. Not the courage to face down a chain of riot police or to be able to say what they think, knowing that they risk going to prison for it. They’ll need that type of courage too, but further down the line. For now Russians need a different kind of courage: the courage to look at life with their eyes wide open and realise how tragic and long-term the situation they find themselves in is. And they need the courage, in these tragic and seemingly hopeless conditions, to go on living, to be themselves and stand up for what they believe in.

Leonid Gozman

Russian opposition politician

Because Putin is doing just fine. But the people, the country, the world… Less so.

Putin’s last term in office was a success after all! Farcical though all these elections and inaugurations may be, they still mean something. They are milestones, where he looks back, re-evaluates and makes plans for the future. I think he’s happy with how things have gone: the economy hasn’t collapsed; factories are working and producing weapons; there is no shortage of food or essential items in the country; his cronies have learned how to get around sanctions; they have adapted to isolation.

The elites, too, are loyal, and have made their peace with eternal war.

The Ukrainian counteroffensive came to nothing; the front line stabilised and Russian troops have recently even been making advances, albeit slowly and with terrible losses; emigration hasn’t caused serious problems; there are still enough weapons developers, and he doesn’t see the departure of Russia’s awkward intelligentsia as a problem at all — in fact, he’s probably happy they’re gone.

The political situation is also perfectly manageable. His enemies are either in prison or in exile, and the most powerful ones are dead. On the whole, the people have got used to the war. There’s lots they’re not happy about, of course, but there are no mass protests and there is no civil disobedience. Life is just as it was before.

The elites, too, are loyal, and have made their peace with eternal war.

Cardboard cut-outs of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping in front of a souvenir shop in central Moscow, Russia, 16 May 2024. Photo: Maxim Shipenkov / EPA-EFE

And for those with an absolutely distorted view of the world, in which the West only wants to bring Russia to its knees, Putin has made the odd reasonable decision. He has maintained macroeconomic stability, for example. He has just had a fairly successful cabinet reshuffle. The new defence minister, Andrey Belousov, is a sensible economist untarnished by scandal, which doesn’t mean he isn’t on the take, but if he is, then at least he doesn’t overdo it, unlike Shoigu, a caricature that people that were glad to see the back of. What’s more, Belousov is smart enough not to interfere in military matters, which will reduce discontent among the military top brass. Nothing much will change for those on the front line, but it’s the morale at headquarters that concerns Putin.

These are the circumstances Russians are faced with, and they need to acknowledge this terrible reality, not delude themselves, and learn to play the long game.

The problems are piling up, of course, and the country is on a downward trajectory. It will all come crashing down in the end, of course, and whatever’s left will become a Chinese vassal, but we can worry about that later. For now, life is fine.

So Putin will carry on doing what he has been trying to do for years: destroy Ukraine — maybe with the odd ceasefire here and there — restore the empire, fight the West, all while tightening the screws at home. More people will find themselves in jail. Not just those who have said or done something, but even those who have thought it too.

These are the circumstances Russians are faced with, and they need to acknowledge this terrible reality, not delude themselves, and learn to play the long game.

It’s difficult not to give up. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian psychologist who survived Auschwitz, said that prisoners who understood why they needed to survive Hitler’s camps had a better chance of surviving. Life was so terrible that many didn’t want to go on and thought about suicide. But if a person remembered, for example, that a loved one in the same situation might need help after the war, they tried to survive themselves.

Anti-Putin protesters at the Russian Embassy in Berlin, Germany, 17 March 2024. Photo: Hannibal Hanschke / EPA-EFE

Russians too have something to live for. Those who have stayed in Russia have children and grandchildren who need to be saved from this insane propaganda. They need people to speak up against this madness.

The people who have been forced to leave can, of course, give up on Russia, think of it as some terrible dream, try to make their children German or Spanish. But that means deleting the past, admitting defeat and wishing they’d left earlier. Not everyone is willing to do that. For Russians unwilling to give up on their past and their identity, there’s a lot to do beyond adapting to a new life and dealing with bureaucracy.

Perhaps most of all, Russians must help each other, at home or abroad, not to lose faith in the future. The country must not be reduced to a series of insane tyrants, prison guards and informers or to meaningless simulacra like the State Duma.

They need to help their compatriots who find themselves in a worse position than they do, not just by putting them up or helping them find their feet in a new home.

Russians have to think about the future, and what happens to the country in the post-Putin era, whenever that might be. A lot will depend not just on what happens within Russia itself, but on what the rest of the world thinks too. If people in the West believe Russians are genetically destined to be slaves incapable of freedom in a country where democracy is impossible and everyone is pro-Putin and pro-war, then when the inevitable collapse comes, the rest of the world will shut Russia off and surround it with a moat full of crocodiles.

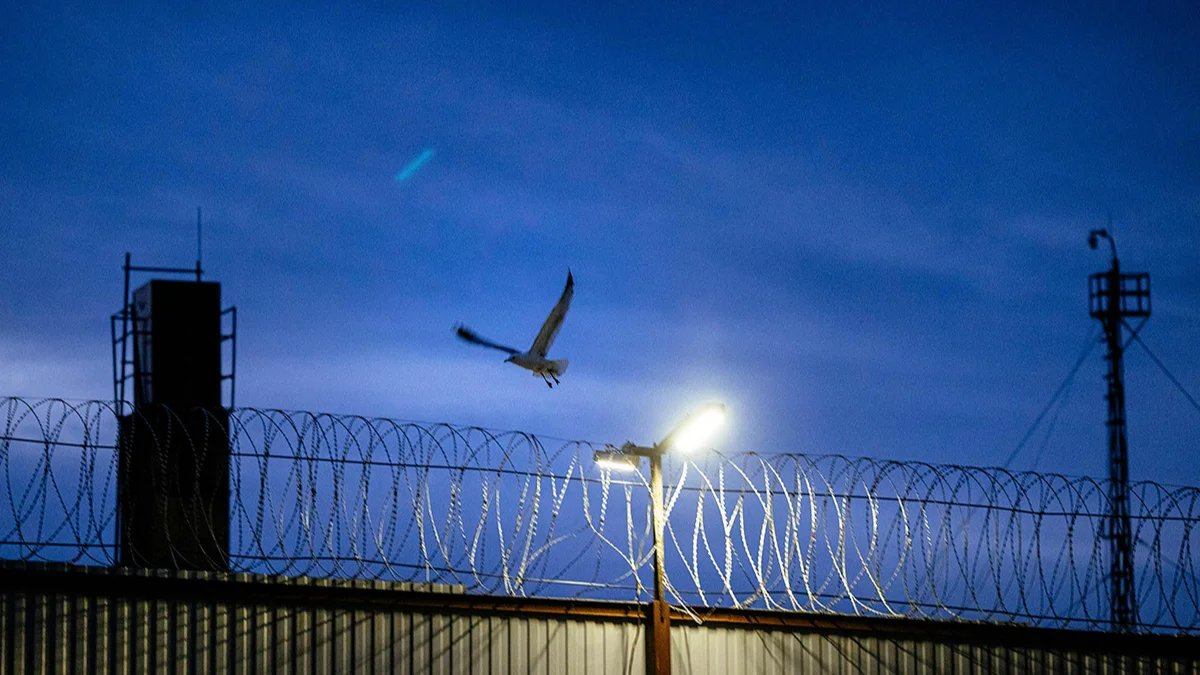

Barbed wire fence at penal colony IK-3, where Alexey Navalny served some of his sentence, Vladimir, Russia, 19 April 2021. Photo: Dimitar Dilkoff / AFP / Scanpix

Russians must therefore convince everyone they can that the country is more than just Putin, as Germany was more than just Hitler, that war criminals and thieves are not the sole face of the Russian people, that the outside world can and should cooperate with those who oppose the current regime and that those people need help: both now and in the future, when Putin is gone.

Rallies help too: passersby in Berlin, Madrid and London see the flags and understand that not all Russians are fascists. Perhaps most of all, Russians must help each other, at home or abroad, not to lose faith in the future. The country must not be reduced to a series of insane tyrants, prison guards and informers or to meaningless simulacra like the State Duma.

Russia has centuries of heroic and often successful struggle for freedom and a great culture behind it. Catherine the Great called Russia a European power. Yes, these are dark days, but it isn’t the end of the story. The situation has seemed beyond hope many times before: under Nicholas I, Stalin, Brezhnev. But change came, and always when it was least expected.

Russians may not know when victory will come or even if they will live to see it. But that doesn’t absolve them of their duty to fight.

Views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of Novaya Gazeta Europe.